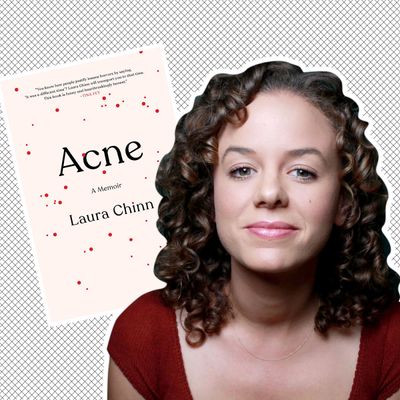

Laura Chinn’s coming of age memoir, Acne, begins with discovering her first zit, at age ten — typical kid stuff, right? Thing is, that’s around where Chinn’s average childhood ends. Shortly after, her parents divorce and her brother is diagnosed with brain cancer, leaving her home alone in Clearwater, Florida, while her mom and brother shuttle around seeking treatment.

Still, as you might’ve guessed, her skin plays a central role in her life story. Chinn made Acne the title of her memoir to show how painful it was for her, even if it should have paled in comparison to the other trials her family was dealing with. “My brother was blind and deaf and in a wheelchair, and I was still jealous of his clear skin,” she says. (At one point, Chinn does go with her mother and brother on one of these journeys, to Tijuana, where she’s prescribed unregulated Accutane for what’s become face-blanketing acne.)

Having parents who were both not all that interested in being parents and consumed by her brother’s disease made her grow up quick: In her memoir, Chinn takes us through her adolescent years of drinking, smoking, having a best friend who broke her bathroom sink by having sex on it, and trying to lose her own virginity. Plus, she struggles through laughing off boys who grab her crotch at school, racist classmates (Chinn’s mother is white; her father is Black), and being by her brother’s side for his eventual death. She drops out of high school but makes her way to an unlikely Hollywood ending in Los Angeles where she establishes a career in television (she’s the creator of Pop TV’s Florida Girls, and has also been a writer and producer on Fox’s The Mick and written for Fox’s Grandfathered).

Chinn says when she started talking about her formative years in writers’ rooms, “I would tell a story that I thought was pretty benign, and they would react in such a horrified manner. Because up until that point I thought that’s what being a teenager was. I thought, like, witnessing gang bangs was a part of everyone’s childhood.” They also said she should write a book.

After struggling with acne for decades, what made you want to write a memoir around it? Didn’t you just want to be rid of it?

Part of it was that I had so much trouble talking about it. I had so much shame around it, and even up until a few months ago, it’s been really hard for me to talk about. And so there was a certain catharsis in writing about it. So I started doing that and then I began to track the fact that acne had been this through-line of my whole life. All these other things are going on, while I’m still dealing with this skin thing. It also felt humorous to me, the juxtaposition between my obsession with my skin and the horrors that everybody else was going through, like my brother having brain cancer.

You write about having a childhood where you went for long periods without adult supervision. What do you think that taught you?

I don’t recommend it as a parenting technique, but I will say it’s made me incredibly capable and not easily overwhelmed by life. When I was in my 20s, my friends would scratch their cars and break down in tears, and they didn’t know what to do. And I was like, “Well, you call an auto body shop, make an appointment, bring your car in.” Since I had been taking care of myself for so long, it definitely made me a very capable adult.

You’re really honest in the book, about everything from getting made fun of for your zits by a lighting guy on set to working as an actor to how lucky you were to avoid harming yourself or others while drunk driving. What was the hardest part to write?

Drunk driving was definitely the hardest; I still carry so much shame for it. The selfishness is deplorable. It’s hard to think of myself as someone who was capable of doing something that destructive, but I was. I wanted to write about it in the hopes that someone else might learn from my actions, but it was challenging to get the words down.

What was your parents’ reaction to reading the book?

It was challenging because I don’t think they knew how hard it was for me. So I think there was a lot of emotion, and it’s one of those things where their cup was so full of taking care of my brother and their stress and their horror of what was happening to my brother, and so in so many ways I think it was surprising to them to hear about all that I was getting into and what my life was like without them. The extent of the danger, almost, how dangerous it was. My mom grew up in a completely different time when they used to run around the neighborhood and they weren’t doing, you know, heroin. So I think it was pretty alarming, the amount of danger that a child can encounter if their parents aren’t present.

I was struck by your stance that you weren’t going to do drugs, that you drew a hard line there.

It saved my life. It was a life-saving decision. It really, really was. I think that there are young people who can do drugs, and they come out the other end, but I think young people who are experiencing trauma, who have experienced trauma, sometimes, drugs can take too big of a hold, and I think I would not have survived. If I had started, I don’t think I would have stopped.

There’s so many instances in the book where you write about people being outright racist around you, apparently unaware that your dad is Black. How did you learn to embrace your identity and stand up for yourself?

It’s funny. I found it all so hard to believe and so ridiculous that there almost wasn’t an evolution. It was like, immediately ridiculous to me and immediately, I knew that I was always going to tell whoever I was in front of that my dad was Black, no matter how seemingly scary this person was or whatever their point of view was, and I don’t know why exactly? Because I was so young and little, but I think because I had the gift of growing up in a household where everyone was a different color I just had such a knowing at such a young age that this is a ridiculous viewpoint and doesn’t make any sense. And so yeah, it was almost just like immediate, my reaction to that was almost immediate. People still don’t know that I’m Black, but I don’t live in a place where there are as many people who would be speaking in a racist manner in front of me. I don’t know if that’s location or the times have changed or I just happen to be around more enlightened beings, but I don’t run into it anymore.

You dropped out of high school. Did you get a GED?

I dropped out of high school in tenth grade, and then I went to a fake high school. It’s a high school in the mail, so you send them cash and they send you open-book tests, then you get a high-school diploma, but it’s not like it’s real. It’s kind of real, but it’s not real.

That’s the education you had when you started working as a writer on television shows in L.A. Did you have imposter syndrome?

Huge imposter syndrome, up until my husband completely shifted my perspective, because I had been in writers’ rooms with all these Ivy League–educated people, and I was expressing my insecurity about that, and my husband said, “But Laura, so few of us went to school for writing.” And I was like, “Oh yeah,” because he went to Columbia for engineering. As I started asking people, they went for all these other reasons and so I was like, They might know more about books or science or something. But so many of us are self-taught even if we went to university. So that helped me a lot. But no, I had so much insecurity around not being educated.

What did you tell yourself to be like, You belong in this room?

Literal affirmations that are exactly that. I do listen and still listen to a lot of affirmations. I used to see a woman who would have me write down affirmations every night before bed that are exactly that. I am Laura Chinn and I deserve to be here. I am Laura Chinn and I deserve good things. You’re just sort of brainwashing yourself to believe that you deserve it. And I recommend college because I think it took me a long time to get that sense of entitlement, but somebody might get it in four years. They can get it easily in four years.

Back to your acne — you tried to fix it so many ways: Accutane, diet, and even the Scientologist-approved purification ritual. Can you talk about how you thought they’d change your life?

Every time I was like, This is the answer. I’m so much harder on myself than anyone else, and when I have a breakout I feel so heavy and there’s so much insecurity and self-hatred that rises to the surface. But when I see a breakout on someone else, I don’t notice. And then if they point it out, I’m like, I don’t care. You’re beautiful. But for myself, one of the biggest challenges of this health issue is that it feels like I’m not allowed to have it. If you have some other health issue, you can have it and you can wear a bandage or a cast on your leg or whatever. But in our society, we’ve decided that this health issue has to be covered up and hidden and you have to be ashamed of it. And so that was always just very hard for me. The shame aspect of it was always very, very challenging, and so every new treatment I was like, I don’t have to feel ashamed of my health issue anymore. It was like lying to yourself. I’m sure people do with every kind of physical thing they wish they could change, right? You think it’s all going to go away and you’re going to be confident. But then honestly I started doing inner work and the confidence came from within more, and all the fantasies about how my skin was going to make me confident kind of went away, and I was like, Oh no, it’s all going to have to come from inside, isn’t it?