Marilyn Monroe was both beautiful and brutalized. Throughout her short life, which ended after 36 years from an apparent suicide, she embodied the contradiction of being one of the most beloved and most abused public figures in the world. In her life and art, her grief fed her glamour. The brutality of her childhood — a schizophrenic mother who didn’t want her, a father who abandoned her before she’d even been born, likely abuse in foster care — created in young Norma Jeane Baker a primordial kind of need to transform herself and her life into the polar opposite of all that harrowing grime. In movies and magazines and imaginations, once-Norma, now-Marilyn made herself synonymous with soft femininity: tits, ass, eyelashes; fur, silk, diamonds. She was the aestheticization of female pain embodied, and this is central to our enduring fascination with her almost 60 years after her death.

In the most recent iteration of this obsession, Netflix’s semi-fictional biopic, Blonde, violence and yearning play at close range. There are perfunctory rapes, drugged blowjobs, and a profoundly disturbing talking fetus in Andrew Dominik’s film version of Marilyn’s life, which was adapted from Joyce Carol Oates’s critically-acclaimed semi-fictional biography. But the hardest bits to watch are the hope that will not die from Marilyn’s face and the desire to be loved vibrating visibly just beneath its surface. It is incompatible with the story we tell ourselves about healing and self-determination and independent womanhood: that an icon who made herself so completely could still spend her life waiting to be chosen. Unlike other icons of her era — Lauren Bacall, Katherine Hepburn — she wasn’t about making men realize they’d met more than their match in a woman. Marilyn was about something that had already begun to fall out of favor in the mid-20th century and has continued declining in popularity ever since, which is the idea of a woman needing a man to love her.

It is hard to blame Blonde’s Marilyn for feeling this way, given the particulars of her life. Her mother, Gladys, was abandoned by her father before she was even born. Gladys believed that were it not for her daughter, he would have stayed, and she was not shy about sharing this with Norma Jeane. Real-life Gladys was a single mother with little money and schizophrenia, facts Blonde extrapolates from to render a mother who tries to murder her daughter in one scene and in another drives Norma Jeane into the burning Hollywood hills during a psychotic break, unkempt and wild with rage. The real Gladys, like the fictional one, was eventually confined to mental institutions. In her mother, young Marilyn saw the twin dangers of letting pain express itself unmediated and in undertaking life without a man.

She did not intend to let either of those things happen to her. History is teeming with women who wanted more for themselves than the little they were given, but the psychiatry is clear: Outrunning the epigenetics of abuse is an arduous and typically lifelong process. The razor-thin line between Marilyn and her mother is that only Marilyn found a way to aestheticize her pain. To use it as fuel to become what the world wanted from a woman — a pliant pinup willing to smile, at least for a little while, in obscenity’s face. In contrast, Gladys’s grief burrowed inward, turning her into the haggard, rageful, unmaternal woman that societies have shunned, othered, and locked away since the world’s inception.

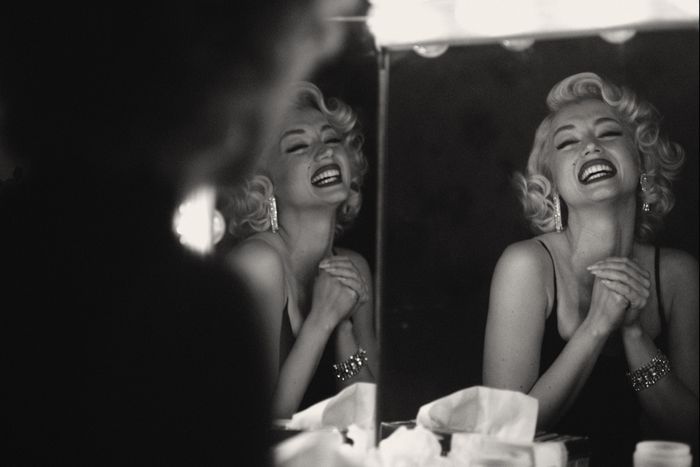

When Marilyn slipped into a tight sweater, glued false lashes onto her eyelids, and parlayed the stammer she’d developed after being molested as an 8-year-old into a breathy aural suggestion of sex, she was looking for a daddy, as she would call all of her future lovers: a father figure who would never abandon her as her own father had. This first manifestation of her grief — to make herself beautiful, to make herself sexy — was the most socially acceptable one she could have chosen. Marilyn cauterized her wounds by making them shine. Unlike her mother, driving headlong into burning hills with a shaking child at her side, Marilyn was able to dissociate from pain while also remaining close enough to use it. To run away from and toward everything wild inside of her at the very same time. We see this in an early audition scene in Blonde, as Marilyn parlays a post-traumatic flashback into extraordinary emoting for the camera; a centerfold girl viscerally remembering a murder attempt by her mother.

This impossible dichotomy would form the basis of Marilyn’s glamour. Glamour is lacquer thrumming with emotion. It’s Marilyn in The Misfits, as Clark Gable tells her luminous face that she’s “just about the saddest girl” he’s ever met. It’s Elizabeth Taylor with her violet eyes and almost pathological number of husbands. It is Joan Didion’s migraine when the Santa Ana winds begin to howl, the titular Virgin Suicides, a doe-eyed Winona Ryder shoplifting, and Sylvia Plath writing with all the lyricism of music about how badly she wants a man to kick her in the face. Glamour is also the contrast between what women are most allowed to be — beautiful, feminine, sexy — and what they are least allowed to be, which is insatiable, angry, desirous, or unwell. How can the same woman cater so perfectly to the world while not catering to the world at all?

To be glamorous in this way is a profound transgression. Is it any surprise then that we have fetishized it? As her mother’s sad story reminds us, Marilyn Monroe is not someone whose darkness would have interested us without the corollary of her beauty. Nor would her beauty have obsessed us without its attendant darkness. Bacall and Hepburn were also beautiful and talented, but it is unlikely a major film studio would ever make a movie about their lives that would generate the controversy Blonde has. The story of beauty is hagiography, while the story of glamour is riveting. What would it be like to allow ourselves to want things that badly? To want them enough to risk being called a dumb blonde, or a bad influence, or a common whore? To seem impervious to these judgements in our flashbulbs and mink? And to break down completely when our desires — in Marilyn’s case, for a happy marriage and a baby — are not delivered, rather than pulling ourselves together like good strong women, who accept any fate as totally fine?

But fetishization is not empathy. And while our feelings about Marilyn Monroe still run hot decades after her death, this fascination may be in part due to our uneasy relationship with the display of female pain among the living. If some of us have to be good strong women, should we not all have to be good strong women? Particularly for beautiful women, visible pain from invisible sources can come with a secret asterisk, an eye roll. We see this in Blonde when Marilyn, awash in bouquets and fan letters, is being zipped into her undergarments by attendants while confessing that she feels like “a slave to Marilyn Monroe” and is exhausted by life as a caricature. “Miss Monroe, you’re cruel,” one of the attendants replies. “Every one of us, everybody in the world, would give their right arm to be you.” Only the visible is allowed to be real for a beautiful movie star.

Near the end of Blonde, a drugged and drunken Marilyn collapses on the floor of a plane flying her to give the President of the United States a blow job, keening and rolling on the ground. She is clearly not okay. But she’s also Marilyn Monroe, so how bad could it be? Flight attendants and Secret Service agents wipe her face, zip her dress, and drag her when she can no longer walk. Blonde has been criticized for showcasing such brutality — one critic called it “violent rape porn” — as if there were something inherently pornographic and unserious about violence happening to glamorous people in glamorous places.

But without the violence, Marilyn’s story morphs into the terrible, familiar, toxic narrative of a fallen angel who destroyed herself, even though it was plainly others who destroyed her. This self-harming girl story is the polite version — sanitized, gussied up, and zipped in its dress. And our insistence on telling it allows the power structures of patriarchy to perpetuate harm over and over without ever being called to serious account.

Our enduring fascination with Marilyn points to something darker in the ether; something darker in ourselves. We still have no place or name for women who are both beautiful and unhappy. We need them to be one or the other. And when they refuse to conform to this dulled, dehumanized demand, we passively point and photograph and judge, thanking our lucky stars that we are not so relentlessly watched, so resolutely misunderstood. It’s so sad, we say when women like Marilyn decide they no longer wish to live as repositories for our repressed fantasies and rages. It’s so sad. And it is. But perhaps what we mean by it’s so sad is that we see in women like Blonde’s Marilyn the futility of living so close to life’s marrow, so perpetually in tune with the deep down thrum. Even Marilyn, who marshaled brutality and desire into such high art as herself, could not walk the impossible tightrope of being a woman who was fully tapped into her emotional register. We were right to temper ourselves, Marilyn reminds us. But we will never stop being sorry that this is what is true.