Shrubs of geranium, azalea, and pine live together on the Chilean artist, poet, and environmental activist Cecilia Vicuña’s modest plot in Washington Market Park’s community garden. Amid Tribeca’s high-rises and posh restaurants, that yards-wide patch of land is both a piece of art itself (perhaps her most personal to date) and an outdoor workspace located a ten-minute walk from her actual studio. “Miniature roses — a miracle!” Vicuña chimes. It’s early September, and there are unexpected blossoms here in her tucked-away refuge of 40 years. The artist’s impossibly low-pitch voice reflects nature’s hymn. Despite the invasive urban hum, she whispers to better hear a red sparrow chirping and pauses to listen to the wind washing over the leaves. A few birds glide past our bench in search of food; the whisper wanes into near silence. “They need native plants to eat, but most in here are not indigenous to the land,” she laments. Small but deliberately designed, her own garden brims with flowers native to Manhattan “and strong enough to survive anything.” For the 74-year-old, mother nature’s unexpected gifts still hold the power to amaze.

Following a half-century spent creating art and poetry largely under the radar, Vicuña’s last few years have, in contrast, been a series of lofty accolades. At the 59th Venice Biennale, back in April, she was the first artist of Latin American descent to receive a prestigious Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement. There, she exhibited a suite of dreamscape paintings and one of her unspun twine and debris installations called quipu (Quechua for knot). Also on display: dried branches and pieces of fishnet collected off of Venetian and New York City streets. This summer, her Guggenheim retrospective “Spin Spin Triangulene” hung alongside a Vasily Kandinsky exhibition. Hers included three new quipus and five decades’ worth of work. And last week, the Tate Modern opened her towering mixed-media installation Brainforest Quipu in its famed Turbine Hall for the 2022 edition of the lauded Hyundai Commission. For that massive quipu, she and a group of museum employees roamed the London streets collecting detritus. Vicuña’s intricate structures, hand-constructed on-site, brim with curious findings. Next year, they will be at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tucson and then the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Santiago. In museums where her work is shown, she makes sure to pause and meditate during installation — as well as simply rest on the floor, lying down with her arms open wide like wings.

This beautiful weaving of the unrecognized and discarded was what first drew Rachel Lehmann, the co-founder of Lehmann Maupin gallery, into Vicuña’s studio four years ago. They’ve represented her since. “Cecilia uniquely ties collective histories of thousands of years with our untold moments through objects and poetry,” Lehmann said during a recent phone call. “Through quipus, we connect with our ancestors and realize we are only a fracture of a bigger knowledge.”

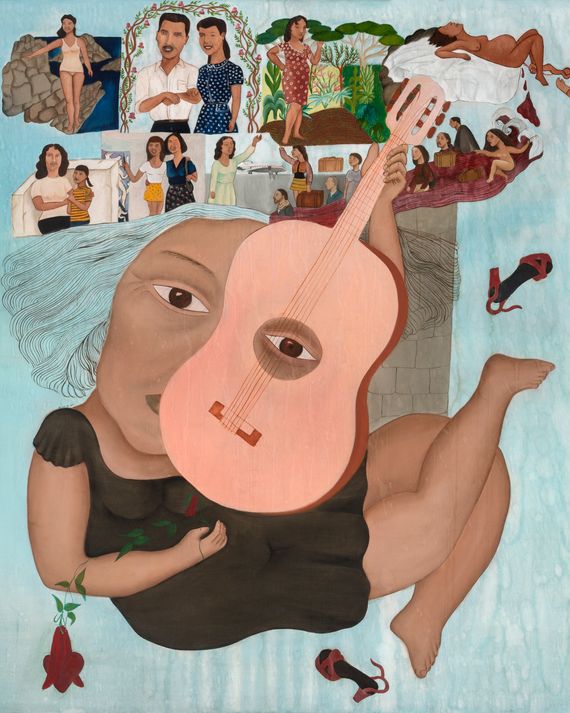

Bendigame Mamita (1977), a surreal painting of the artist’s mother depicted as being immersed in a dream, remained behind closed doors in her 97-year-old mamita’s home in Santiago until the Biennial. A detail from the painting is being used as the face of the international art exhibition, the image covering the sides of water buses up and down La Serenissima.

Outside of this new globetrotting, life, for Vicuña, appears to move at the same pace it did in the 1960s and ’70s. A bit surprising, given that back then she created impromptu performances on the streets of Santiago and witnessed her paintings being destroyed by the Pinochet regime. “They saw my work as weapons,” she says with an emphasis on weapons. During the fascist crackdown, the director of the Museum of Fine Arts in Santiago saved Vicuña’s painting of Karl Marx from the (literal) bonfires by changing the name above his portrait to Charles Darwin. The piece survived and now resides in the Guggenheim collection, but a majority of her work from the era wasn’t so lucky. “Unlikely,” she says of the possibility that some might have in fact survived outside her knowledge, “but if someone out there managed to hide and kept any of those works, that would be fantastic.”

Her past is irreversibly woven with the present, much like her elegantly knit quipus. Vicuña’s Palabrarmas drawings illustrate short but striking words such as verdad (truth) or mentiras (lies) in cursive fonts that resemble comics. Fifty years after their creation, the designs were recently resurrected and transferred onto protest banners during civil protests in Chile. “I am honored to see them being used for a purpose, although it has taken people a while to find a meaning in them,” she says.

While political, her poems are breathy utterances with mystic prompts. Utilizing both words and fragile found objects in her work is “a metaphor for language’s mortality — they come and die, which brings a beautiful transformation.” The real tragedy, in her eyes, is demise without rebirth, “the death we are imposing onto nature with no renewal.” Among her admirers is Chile’s current 36-year-old president, Gabriel Boric Font. A fan of her 1971 poem Mission, about two lovers kissing to promote socialism, the world’s youngest state leader invited Vicuña and her mother to the Government Palace in Santiago last July. Meeting her nation’s new left-wing president was a thrill, but Boric gained extra points when he greeted her mother first. “To me, that was an indication of his soul and how enlightened he is.”

Little gestures matter to Vicuña, whose bodily presence, like her vocal radiance, is restrained but determined. Like the vulnerable materials she suspends — feathers, shells, seaweed, fishing wire, yarn — she maneuvers herself around her downtown Manhattan stomping grounds with gentle precision. Given the generous scales of her quipus, her studio, located on lower Broadway, is surprisingly small, occupied by a few unfinished paintings, tubes of paint, and printouts.

Late summer heat kept her from donning one of her signature colorful woven jackets or wool leg warmers during our visit, but she had braided a strand of red-dyed animal hair into her own. Craft of some kind is her matriarchal lineage, one still practiced by her mother, who knits every day. Her earliest memory is crawling across the floor to see the light through her mom’s colorful threads. “I was in an enchanted universe because the threads connected me to other dimensions of beauty and imagination.”

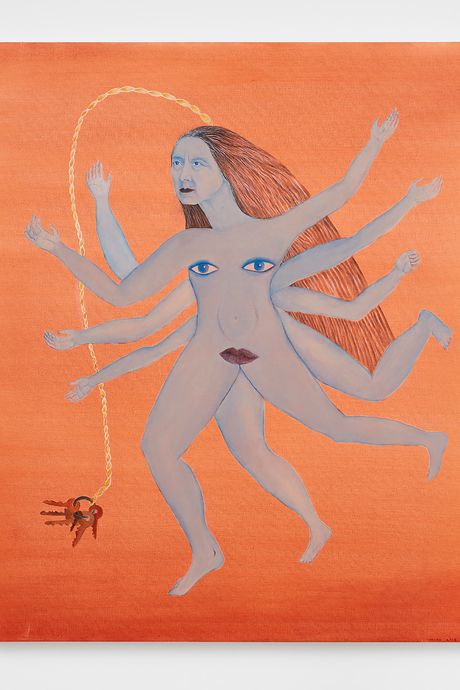

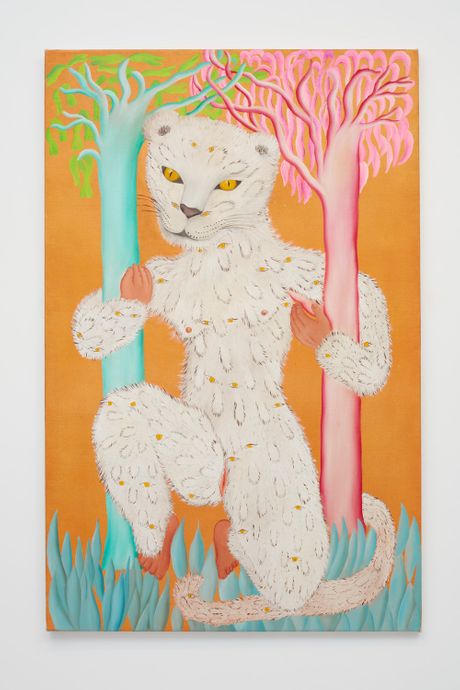

The artist visited the U.S. for the first time in 1965 on an American Field Service scholarship and again in 1969, which coincided with a desire to make Surrealist paintings outside of western art’s prevailing narrative of reality versus abstraction. From the height of this era, Leoparda de Ojitos (1977), currently on view in Venice, shows a frail leopard standing between a pink and a blue tree. Her furry skin covered with eyes, the feline’s own oculus radiates a sexual peril. Although positioned lower in the pastel-hued vertical painting, her vagina is central to the juxtaposition of a mythic animalism. “There is yesterday, today, and tomorrow, but what about our dreams and memories?” Vicuña asks. Nonlinear time fascinates her for its ability to reveal potential in the subconsciousness.

Vicuña was attuned to nature’s tangible and ethereal promises from an early age, having spent her childhood outdoors roaming her family’s cottages, gardens, and studios in La Florida, a commune in southeast Santiago. While her father was a lawyer of European descent, her mother was a gardener and singer with Indigenous roots, and she was surrounded by grandparents and other relatives who were immersed in their own art-making. Her aunt Rosa, a sculptor, was her first mentor. She let a then-14-year-old Cecilia into her studio to show her the great potential when an artist has their own space. A year later, after his daughter converted her bedroom into a makeshift atelier covered with paintings and drawings, Vicuña’s father knew it was time to give her a space of her own. And so he built her a studio that would be her workspace for the next nine years until she moved to London to earn a degree at the Slade School of Fine Art. “One truth might be that he wanted to get rid of the mess,” she laughs. “Other truth is that all women in my family were artists with their own studios, and he probably just wanted to make me happy.” At age 18, El Corno Emplumado, a respected Mexican literary magazine at the time, published her first poems.

Vicuña’s father never wanted her to be an artist “because artists had always been misunderstood.” But nature, and fate, had their own plans. After high school, Vicuña’s plan was to receive a degree in architecture. Then, one January day in 1966, she was walking along the water when she was struck by the site of “twigs, feathers, branches, and some plastic” accumulated on the shore. “I turned around and realized all the debris was around me,” she whispers. She also remembers an overwhelming medley of noises — kids screaming, a helicopter hovering. That day, she was inspired to create the first of her precarios. She exhibits small versions on gallery and museum walls and transforms bigger groupings into suspended large-scale quipus. In both forms, they are reminders of what we leave outside.

In their existence and their evanescence, the earth’s offerings ebb and flow between visibility and disregard. As she combines words into verses of resilience on paper, so does Vicuña bind objects with respect to their pasts and hopefulness for their future prospects. She occasionally revisits that life-changing beach in Chile. Today, there’s an oil refinery nearby. “The sea gets blacker every time, and the debris hitting the shore is nothing but plastic now.”

Working on the art system’s periphery has given Vicuña courage. Today, she fears no failure “because most art fails.” Her understanding of achievement and loss are intertwined, hermetically codependent, and almost indistinguishable. “A proposal for a way to exist” is how she describes the purpose of art. Any invitation to participate in collecting discards off the street, chant in a ritual, or simply sit under one of her quipus is like a seed with endless possibilities to flourish. “True failure,” she says, “is our collective disregard of the destruction we have caused on nature.” A day before our park date, Chile voted against a new constitution that would invest in environmental protections and efforts to combat the water crisis. Vicuña is devastated and hugely concerned about her homeland’s future. “I was a teenager when everyone in Chile thought we would drown, and in the future, we will be one of the countries left without water.”

Defeatism and desperation are absent from Vicuña’s vocabulary. She was neither when the military threw Sabor a Mí, the manuscript of her first poetry book to be published in her country, into the sea in 1971. Nor is she today, when she realizes her garden needs watering in the late summer sun. The job demands collaboration: I turn the faucet; she unrolls the serpent-like hose. The geranium, the azalea, and the surprise rose all are quenched. Is this the botanical version of a painter putting the final touches to a work of art? She has a flight the next day to London, and much collecting to do on the streets there. But parting ways with the work, “the chronicler of her being in a moment,” and leaving her studio is “strange and hard.” For Vicuña, there is no difference between the process and the result. “The process is the work itself because I want to be in it, with it.”