In the opening pages of Fatimah Asghar’s When We Were Sisters, an immigrant father leaves home to get bunk beds for his three children and is murdered in the street. His body is sent to Pakistan. His “coven” of children — the eldest, Noreen, followed by Kausar and Aisha — is plummeted into orphanhood and watches his funeral on VHS. The three are taken in by an uncle so terrifying that his name is redacted. He steals their father’s inheritance and their government checks, funneling it all to his two half-white sons in a wealthy suburb. Under the inconsistent guardianship of their frequently cruel but occasionally warm uncle, the siblings raise each other as painful and imperfect “sister-mothers.”

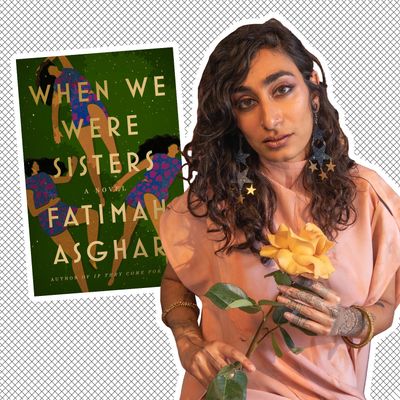

Asghar is a poet and screenwriter best known for their poetry collection If They Come for Us (about the 1947 Partition of India and Pakistan), co-creating Emmy-nominated web series Brown Girls, and recently serving as a writer and co-producer for Ms. Marvel. When We Were Sisters is their first novel, but they know orphanhood intimately, having lost both parents before they turned 5 (their mother fled Jammu and Kashmir following Partition violence). They wrote the novel out of a place of pain and isolation, but the finished work pays homage to makeshift families and alternative communities. “Something I’ve learned through my life is that community is beautiful and transcendent. It morphs. It changes. It grows,” Asghar says. Threaded with vignettes and poetic interludes, the novel constantly morphs into the shape of Kausar’s new families — whether with temporary “aunties and uncles,” their sisters, their uncle in a tender moment, or their lovers. No structure, even among siblings, is fixed. Asghar wants to pivot away from prevailing orphan narratives in which ragtag siblings come together and form an “ideal family.”

There is no idealism in When We Were Sisters. Shared trauma disintegrates relationships as much as it strengthens them. Monsters aren’t just monsters; they are subject to demons of their own. “I wanted to show the tightness of how tight siblings can be, how dysfunctional they can be, and what happens in separation,” says Asghar. “As older characters, they need each other but are, in some ways, almost like strangers. Yet they know each other so deeply and profoundly.”

In the afterword to the book, you mention you wrote it in a period of isolation. What was your inspiration?

I started writing the book in 2018. I was going through a period of extreme rejection and feeling a lot of abandonment wounds. In this super-low moment, I started coming to the page and writing. I didn’t know what the thing I was writing was. I let the character and vignettes reveal themselves to me. It was a dark moment in my life. All I had was writing. It really helped me move out of that space. Exploring these wounds I had around being an orphan, I got to explore the question of how much of my loneliness was of my own making. What does it look like to be in a story of your own loneliness? The book helped me come out of that a bit.

You’re a poet and have written a web series and produced and written for television. What was it like switching over to the format of a novel?

It was one of the hardest artistic endeavors I’ve ever done to be honest. I have written in a lot of genres but never fiction. Poetry and even screenwriting have elements that have always felt very collaborative to me. When you write poems, you do readings; you perform at open mics to your community or publish them individually. This process was not that. Very few people had eyes on this novel, and creating something that required such quietness and isolation to make was different and difficult. But it was one of the most fruitful artistic projects I’ve ever done. I feel fundamentally like a different artist at the end of making this work.

Throughout the novel, Kausar seeks out new configurations of family and love. You’ve written about being an orphan in previous works. What are the challenges of makeshift family, and do Kausar’s experiences resonate at all with your own?

This book takes a look at both the beauty and dangers of makeshift family. You see Kausar struggle when there’s a lack of consistency: There are these moments of, Oh my God, we’re a family, and it’s so beautiful! But then it’s, like, Wait, this is really difficult, and I can’t rely on anyone being here. Kausar realizes they can’t rely on their auntie and uncle being there, because they leave. They can’t really rely on the uncle, their guardian figure, because he’s so inconsistent. Then there’s the overreliance on siblings, but what happens when siblings fall out or have hardships?

What you see is a character existing in an extreme margin who’s trying to figure out how to live in this world, how to be and how to love, when few things in their life are consistent. There’s a lot of people who don’t know that struggle. But there’s others who went through different systems of care, whose families aren’t traditionally recognized by the state as “family” — people who create alternate structures. That’s what the protagonist is up against. Sometimes they can access feelings of love and care and community, and sometimes they feel far away from them. There’s definitely overlaps between my life in this book. It’s fictionalized, and these siblings are not my siblings, but there are certain events and feelings that are deeply, deeply true.

Complex sibling relationships, including sister-motherhood, are central to the story. We see grief fracture three ways between Noreen, Kausar and Aisha. We feel the specter of the uncle’s sons — siblings who are beneficiaries of that grief. How did you develop those relationships?

Many of my relationships are complicated, and very few of them are static or set in a container society would understand. Talk to any queer person, and they have a bunch of friends they might have had sex with. There’s more fluidity in our friendships, our community, and our relationships in ways that traditional society doesn’t fully accommodate or understand. For me, this book is about every single relationship that is blurred and multilayered. I’ve had parental figures in my siblings. I’ve projected that onto them, and they’ve acted that way. I’ve had friends who are like siblings and relationships with people who aren’t blood but treat me like I’m their kid.

These things are accurate in my world but don’t have “legitimacy” in society. Even with the uncle relationship — they’re not his kids, but they’re kind of his kids. His sons are the beneficiaries of their grief, but people are the beneficiaries of their ancestors’ decisions. It’s hard, because it’s not really their decision or fault, but they are beneficiaries. What do you do with that? That happens with all of us in various ways. What we inherit and what we disinherit is an interesting question to think through.

Tell me about the decision to redact the uncle’s name from the text and about crafting him. He has so much duality: He can be abusive and exploitative, mysterious and frightening, but tender and small. Later on, he opens up to Kausar about his Partition trauma.

A lot of times, when we think about people who are potentially abusive or have caused harm, we talk about them as though they are monsters and flatten them. What we really remember is the bad. I don’t want to speak for anyone, but I think that idea of monstrosity is not helpful. It’s a way of dehumanizing people. That’s not to say those who are abusive deserve all this humanity, especially when they’re not accountable for what they’ve done or have hurt vulnerable people, but it was important for this character not to be one-dimensional. I wanted to evoke how fearful he was, but I didn’t want that to be his only tone. It was important for me to include moments of his tenderness with Kausar. He’s hinting at a larger history Kausar is unaware of and that they will never know.

In most of my experiences with abuse, ones that are really complicated include bad moments but also moments of goodness that feel like, Oh, maybe I can root for this person. If someone is just bad point-blank, it can be easy for you to be like, I don’t want to fuck with them. But if they show you a capacity for good, you might stay in the relationship longer, believing something is possible when it’s really hurting you. That’s the tension I was trying to capture. Kausar’s really trying to get family, and this person is, in some ways, most proximal to that, even when he’s terrible to them and their siblings.

The uncle calls the kids “prostitutes” when they’re young and seen talking to boys, imbuing them with sexual shame before any of them has explored their identity. What do you think the impact of that shame is?

They’re being shamed before they know what’s going on. The uncle is questioning Noreen about having sex, and Kausar’s watching on, like, I don’t know what this is, but I know it’s bad. I don’t know how to talk about it fully. When someone is shamed so early on, it quickly makes them vulnerable to sexual violence and danger. There’s no outlet to embrace or even know what your body is, what’s an okay touch and what’s not an okay touch. Kausar doesn’t have the language for it when they’re put in not-okay situations, but they’ve been embedded with so much shame that they can’t even talk to people to help realize that.

The book explores how makeshift families and even blood ones end and fracture. By the end, Noreen, Aisha, and Kausar are somewhat estranged from each other. How did you approach that?

To me, the experience of having siblings is one of, Damn, at one point, we shared the same skin. Then you grow up and have your own lives, even if you’re still cool with each other. There’s an element of, Oh my God, it felt like we were the same person, and now we’re not the same person anymore. You make decisions I don’t agree with. I make decisions you don’t agree with. That’s part of being a sibling and growing older. These relationships are so fascinating and complicated, hold so many things, and are incredible in the breadth of what they are. When you think about the effects of trauma, that is a response: I don’t want to deal with this thing that happened to all of us. I’m going to get rid of anything that reminds me of it. I just want to be able to make my life on my own terms.

There are so many western orphan stories where siblings, despite all odds, stick together and make it work and become this ideal family. I wanted to explore what happens when you’re not taught what family means and trying to do that. A lot of the time, it’s not ideal. It’s messed up. It’s convoluted. They all have really different relationships at the end, but that’s okay. You can feel how much love they have for each other. Love looks different to different people. You don’t have to be all up on each other all the time.

This interview has been edited and condensed.