Answer honestly: Would you settle for being a Tampax-brand tampon, allowed just eight to ten hours of onetime-only physical contact with the person you love most, if that’s what it took to be with them? Would you accept that deal, understanding the reality of a tampon’s situation: to get tossed in the trash or just “go on and on forever swirling round on the top” of a toilet, “never going down”? Sorry, but I don’t believe you love anyone that much. You know who does? And who had the courage of his convictions to say it out loud? King Charles III, who during a 1989 phone call moaned about how it would be “just his luck” to get reincarnated as a tampon adjacent the knickers of his then-mistress and now wife, Queen Consort Camilla. When recordings of the phone call leaked in 1993, the episode known as “Tampongate” (or “Camillagate,” depending on your preference) emerged as an acute embarrassment in a decade crammed with royal scandals — one moment of many that the British monarchy likely didn’t want to see reenacted on Netflix’s The Crown.

The show’s fifth season covers 1991 to 1997, or Charles’s contentious divorce from Princess Diana, and for weeks ahead of its release today, palace aides and the king himself have reportedly fumed over its prospective contents. Senior royals reportedly “moved to protect the reputation of the King” and the newfound popularity he has enjoyed during his first, fussy days on the throne. Former prime ministers John Major (who also happens to have presided over a party mired in “sleaze” during this stretch, though, conveniently for him, writers excised all mention of those incidents from the plot) and Tony Blair hit back at flawed depictions of recent history. Dame Judi Dench publicly pleaded for a disclaimer to be added clarifying that The Crown is “fictionalized,” apparently worrying that some viewers — particularly those “overseas,” a group that includes whole countries full of people not subject to the monarchy’s jurisdiction — might not realize they’re watching a TV drama staged by actors rather than a spicy documentary. But I’m not sure Charles needed to worry. In a season that often feels like a reheated reading of The Diana Chronicles, Charles once again enjoys an uncommonly sympathetic portrayal.

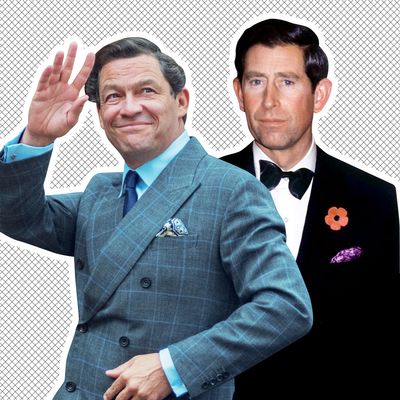

When he confirmed that season five would cover Tampongate, Charles actor Dominic West said he and his co-star, Olivia Williams, approached the subject matter with empathy — just “two middle-aged lovers being sweet to each other,” he told The Guardian, and then having their intimate exchange splashed all over the front page of newspapers the world over and made available for a small fee on special hotlines. “Imagine how awful that is,” West added correctly. “It just strikes you as being a horrible breach of privacy that no one should have to suffer.”

That’s what Tampongate has always been: a gross overreach by too-hungry news outlets that, years down the line, would be busted for hacking royal phones and publishing their findings. While the palace and parts of the public were horrified by the tampon tape’s contents when they came out, the actual conversation is chaste. Charles and Camilla don’t even approach phone sex. They joke, they laugh, they indulge their own weird humor and a shared wistfulness about not being able to hang out all the time. What comes through, and what reportedly wounded Diana when she read the transcripts, is how clearly they adore each other. The Crown’s Princess Anne, played by Claudia Harrison, consoles her brother that, while the exchange was a bit “gynecological” for her taste, Charles and Camilla “seemed gloriously human and entirely in love.” She adds, “For that alone, you deserve some credit, in this family especially.”

Since introducing a grown-up Charles in season three, The Crown has tried to give him credit. It has taken a humanizing tack with the character, bringing to life a lonely childhood with preoccupied and distant parents, a miserable stint at a Scottish boarding school, a thwarted shot at real love, an arranged marriage to a teen he didn’t really know, and a perennial obligation to set aside his comparatively progressive opinions about the country and mutely do his duty. The Telegraph called The Crown “the best PR he’s ever had” even as Charles himself chafed at the factual inaccuracies. In the show’s third season, the framing of his pre-investiture stint at Aberystwyth University in Wales reportedly enraged him; in the fifth season, I imagine it’s the suggestion that he once considered staging a coup based on a single public-opinion poll. That’s what ex-PM Major was upset about, anyway, calling the imagined conversation a “barrel-load of nonsense.” Had Charles ever toyed with overthrowing his mother, that would indeed have been treason, so you can see where he might be annoyed. The record reflects that the most the current king ever did was air his opinions (ad nauseam and sometimes directly to political leaders in letters The Guardian has described as “policy demands”) on the ways he believed the country could be better run. The Crown is not the only drama to depict Charles as eager to present himself as the modern monarchic alternative — please see 2006’s The Queen for more on that — but few others go so far out of their way to help you see his side of things.

In a season primarily focused on Elizabeth Debicki’s Princess Diana, Charles really gets only one episode to himself. It begins with Tampongate and ends with a promo for his youth charity, the Prince’s Trust, which “has assisted 1 million young people to fulfill their potential and returned nearly £1.4 billion in value to society.” That’s according to the epilogue note, which plays over a shot of West’s Charles joining a break-dancing circle and noodling around for the crowd. In between, we see him advocating for such reforms as “ending the bar on the eldest daughters inheriting the throne” and making the monarchy fund itself and a focus on the environment, ideas that inspire zero interest from the crustier members of his family.

But by the time we get to the break-dancing montage (a real thing that happened in 1985; here’s some footage for posterity) the episode risks looking like a monarchist ad spot, not least because of the facts it gets wrong. Take the then-prince’s 1994 interview with Jonathan Dimbleby, the one in which he admitted to cheating on Princess Diana after the marriage “became irretrievably broken down.” In contrast to the ramblingly incoherent framing of Camilla as a “great friend” that Charles gave, a snippet of which you can see here, West’s Charles navigates the scrubbed-up version of his answer with poise. In The Crown’s retelling, the segment is billed as enough of a success that Charles believes he can set up his own court. Not so in reality. In the ’90s, the adultery admission overshadowed most everything else Charles said in the segment. “In one stroke he’s wiped out all the good will he’s built up over 12 months,” royal biographer Brian Hoey remarked to the New York Times at a screening of the interview. Tabloids handed a victory to Diana, while about two-thirds of the British public (according to one poll) saw the disclosure as disqualifying for Charles’s future job. “He is not the first royal to be unfaithful. Far from it,” read one Daily Mirror article, according to the Times. “But he is the first to appear before 25 million of his subjects to confess.”

None of which is to say that Charles deserves a hatchet job, just that The Crown applies a predictably shiny gloss to his reputation. It largely ignores his allegedly explosive temper except in situations in which rage might be warranted — Diana’s damning Panorama tell-all, for example, elicits some fist-pounding from West. But this Charles doesn’t choke his valets, doesn’t defenestrate furniture during arguments, and doesn’t travel with his own personal toilet seat, as his real-life counterpart is rumored to have done. No one is squeezing this man’s toothpaste for him, and no one is getting reamed over a faulty pen. This Charles is described by his own fictional family as a formidably strong ruler and avant-garde thinker rather than the quibbling author of whining complaints certain biographers have evoked.

If Charles lost his divorce from Diana in the real world, he arguably wins it here — Debicki’s uncanny Diana gets at the princess’s (justifiable) paranoia, her vanity, and her petulance in a portrait arguably truer to life than West’s. Fiction can work in the monarchy’s favor, too, and that’s arguably The Crown’s greatest trick: Guessing at the feelings and motivations behind people most of the public can’t ever really know, it manufactures an impressive degree of relatability for remote multimillionaires. It successfully positions astounding inherited privilege as a burden, allowing the viewer to understand how much it must suck to exist as cogs in ancient machinery, always having to shelve their feelings and opinions and desires in service of an ideal. The obligation toward impassivity while the press casts your family members as “players in a royal soap opera,” to quote the New York Times, probably grates. But public scrutiny is part of being a public figure. If the royals’ goal is continued relevance, a high-production soap is probably preferable to the tabloid churn. I imagine Charles hopes to one day move on from his mortifying menstrual ode, but he should be thankful The Crown didn’t. It’s the most endearing he’s ever looked, break-dancing included.