Inside the Fashion Institute of Technology’s Museum at FIT, Kool K and DJ Lee Rock pose in front of a busy store display wearing Lee Jeans. Down the steps, a black letterman jacket from New Jack City and a pair of graffitied jeans from Russel Simmons’s Def Jam University sit behind glowing glass cases. The lyrics to Biggie Smalls’s “One More Chance” — “I stay Coogi down to the socks, rings and watch filled with rocks” — faintly fills the next, much larger room filled with hip-hop history artifacts. To the left, a monitor shows a 3-D video of natural-diamond-encrusted chains famously worn by Cardi B, A$AP Rocky, and Drake. To the right, Adidas wedge sneakers and leather Christian Louboutin pumps sit in a case beside Adidas shell-toe sneakers and a pair of Nike Air Jordan 10’s. As purple and orange lights bounce off the white walls, the Migos brag about their jewelry and designer clothing: “Versace, Versace, Medusa head on me like I’m ’Luminati.” Then, amid the tall scaffolds bearing sports jerseys and leather jackets, Pop Smoke gloats, “Christian Dior, Dior, I’m up in all the stores.”

These are the sort of tributes you’ll find inside Fresh, Fly, and Fabulous: Fifty Years of Hip Hop Style, an exhibit co-curated by journalist and FIT professor Elena Romero and associate curator of costume Elizabeth Way (who have also co-written a book with the same title), celebrating the relationship shared between hip-hop and fashion over the last 50 years.

“Our exhibition shows in many, many ways how looks that were either generated within or greatly popularized by hip-hop culture have changed the way we all dress today,” Way says. Romero, a guest curator at the museum, first pitched the idea for Fresh, Fly, and Fabulous in 2018 and soon began working with Way to tell the story of fashion in hip-hop.

“It starts off with a concept that we illustrated on a vision board. And that vision board changed quite a bit in terms of all the different looks and categories that we wanted,” Romero says. “Ultimately, we wanted to find brands that could help tell a particular story within the themes that we thought and identified, that were really important in the evolution of hip-hop style.”

Over the course of the next four years, Romero and Way reached out to designers, archivists, and photographers to amass more than 150 pieces of clothing, shoes, and jewelry that have become symbols and staples of hip-hop culture from over 50 donors.

The co-curators used connections from Romero’s decades of experience as a hip-hop fashion journalist to speak with industry veterans, such as Sal Abbatiello and Shara McHayle, and to choose pieces from the collections of lenders including Gucci Americas, designer Claudia Gold, and Romero herself. “We have pieces from Ralph McDaniels’s personal archive,” Way says. “Also from designers like April Walker and 5001 Flavors.”

The exhibit is organized by themes — customization, film as a vehicle for Black culture, sportswear, the color pink, Afrocentricity, Black pride, and women’s fashion — rather than chronological order to highlight the variety of trends and motifs.

“Many people think that the ‘hip-hop look’ is this one monolithic group which generally tends to be baggy jeans and logoed merchandise,” Romero says. “As you’ll see walking through the exhibit, while that is a component of the hip-hop style, there are many other levels to that.”

A tailored, multicolor striped suit by Marc Ecko and an orange ombré silk organza Rocawear dress at the exhibit show that formalwear and luxury is as much a part of hip-hop style as fitted caps and fat shoelaces. Standing between the Rocawear dress and a bomber-style jacket patterned with NFL-team logos, a Gucci ensemble worn by Dapper Dan in 2021, complete with a blush-pink ascot and white Gucci sunglasses, is one example of diversity within hip-hop fashion.

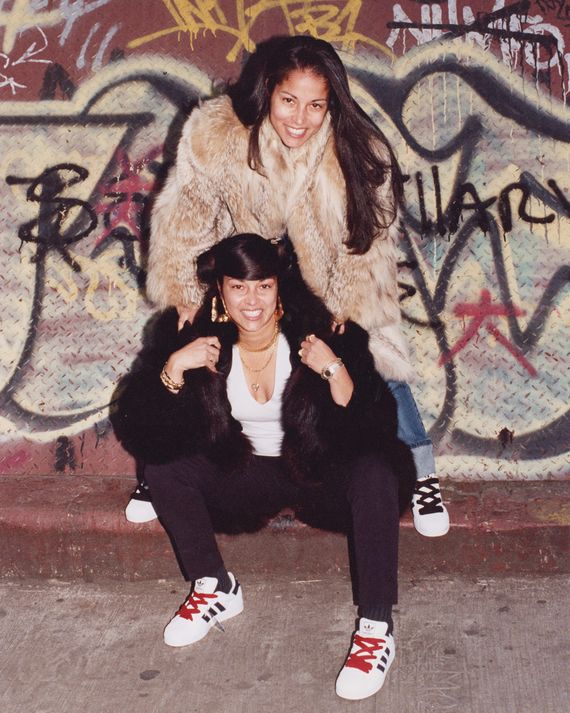

Among other accessories worn to elevate casual and formal outfits like belts and hats, microthemes of handbags and hoop earrings throughout the exhibit point to the subject of women’s fashion. “In the earlier days, women had to dress like the boys,” Romero says. “But as you’ve seen over time, females have made their own statement with accessories and their hair and nails.” As women began to take over the hip-hop scene, they paired sneakers, baggy jeans and sweat suits with asymmetrical haircuts and bamboo earrings as “different ways in which women identified their femininity,” Romero explains.

Bamboo earrings, alongside Fulani hoops and doorknocker hoops, became an emblem of “around-the-way” girls like Salt-N-Pepa. As the hoop earring continues to be a cornerstone of the culture, a bejeweled manicure set by “Queen of Bling” Jenny Bui showcases the use of acrylic nails as statement pieces.

“Hip-hop style, even though it might have been male driven, is both for men and women,” Romero says. “As women of color, we were really intentional about showing both male and female fashion. A lot of times, the stories of women get taken to the sidelines, and right now, the female rappers are really fashion luxury muses.”

While the origins of many of the museum pieces range from the late 1970s to the early aughts, many are still style staples today, reflecting the influence of everyday people and their relationship with hip-hop on mainstream fashion. In the 90s, Timberland boots, leather jackets, and puffer jackets were primarily investment pieces worn by working-class consumers, particularly those in Black and brown communities. As hip-hop culture began to dominate popular American fashion, brands like Moncler and Ralph Lauren began to produce elevated versions of these “traditional” streetwear pieces.

“It’s important to go back to the roots of hip-hop and think about the Black and brown communities,” Way says. “The designers who created these looks, they’ve been very important in shaping American fashion and then disseminating that out to the rest of the world. So we want to make sure that those originators are recognized.”

Those designers include Misa Hylton, April Walker, and Dapper Dan, all artists who’ve been influential in marrying high-end fashion with streetwear. Meanwhile brands like Russell Simmons’ Phat Farm, Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs’ Sean Jean, Jay Z’s Rocawear, and House of Dereon by Beyoncé and Tina Knowles, also on display in the exhibit, gave consumers an affordable way to embody and represent their favorite artists.

The Fresh, Fly and Fabulous: Fifty Years of Hip Hop Style exhibit is a time warp, transforming the Museum at FIT into a universe where all versions of hip-hop exist at once. Even though style and culture in the hip-hop community have evolved in the last five decades, the thread between the old and the new proves that the roots of hip-hop are steadfast and still growing.

“As I’ve been an observer watching who comes into the exhibit,” Romero says, “it doesn’t matter where they’re from, or what their ethnic or racial background is — everyone is finding something that they recognize. It’s not the same way going to, let’s say, like a museum that has objects from the 16th century. It almost feels like a family reunion.” Fresh, Fly, and Fabulous is open now through April 23.