Think of your desired reality: Write down a detailed script of exactly what it all looks, feels, sounds, and smells like. Picture the money piling up in your bank account. Wear the clothes you want to fit into and the body will follow. Now look down at your phone, and picture it: a notification. It’s a text from your crush. You are such a lucky girl: Remember that.

Welcome to Manifestation TikTok. Here, anything is possible as long as you (literally) set your mind to it. Manifestation TikTok is nothing new: In 2020, #manifestation had 3.4 billion views. Today, it has 29.2 billion. This isn’t a pandemic trend; it’s a signal of a post-lockdown reality. And it’s perhaps one of the platform’s (and internet’s) most popular subcultures. It includes all things #manifestation: New Age thinking, The Secret revivalism, mind-set-hacking, visualization, moodboarding, journaling, meditating, tulpamancy, Delusional Eras, reality shifting, and, more recently, Lucky Girl Syndrome. The proverbial times have given people online ample reason to hate reality and go on far-off quests for another one. After the onset of the pandemic, Google search trends for astrology, witchcraft, and spirituality skyrocketed. The manifestation-coaching business is now booming (and scamming). What was once niche is now mainstream and has become even bigger business, both online and off.

Together, this constellation of trends makes up an expanded universe of lifestyle and wellness practices all in service of pursuing a desired reality: one that’s better, easier, in which we’re all richer, hotter, more lovable, and less depressed. We might not be experiencing collective delusions of any significant scale, but we’re definitely wriggling under reality’s ever-tightening hold.

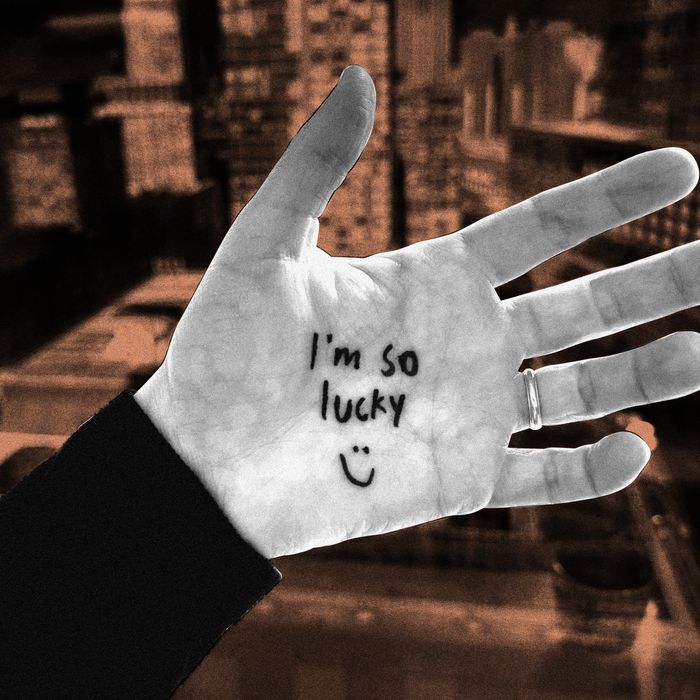

The latest of these trends, Lucky Girl Syndrome, has distilled the last three years of wishfulness into a simple phrase you can write down in your journal or repeat in front of the mirror: “I’m so lucky. Everything just works out for me.” If you scroll on TikTok, you’ll see thumbnails for what look like “clean girl” makeup tutorials or “that girl” morning routines: matching loungewear, thick glass straws drawing green juice or iced coffee into a tanned face. Onscreen text asks viewers to come hither and learn all about Lucky Girl Syndrome — why you should know about it and how to harness its power — drawing viewers into the trend, and with great success: #LuckyGirlSyndrome has almost 515 million views on TikTok. Its promise is simple: The power to bring forth the life you want, say the Lucky Girls, is within your own mind, and you need only repeat this simple phrase (or affirmations like it) to channel it.

Lucky Girl Syndrome has been dismissed as just another TikTok trend — one that gives rich white girls–cum–influencers an opportunity to repackage their privilege as a product of manifestation or a positive mind-set. But Lucky Girl Syndrome and its massive popularity is a testament to how people yearn for any tool they can get their hands on to help them move to another reality, if only just in their minds.

Samantha Palazzolo is one of a handful of people who went viral for spreading the Lucky Girl gospel. “I really just always believed in the power of manifestation,” the college freshman from Springfield, Illinois, tells me. “The power of dreams and the desires that you have and your ability to create those in your life.” She explains in her viral TikTok that repeating that phrase — when she experienced either a stroke of luck or a strikeout on something she wanted — made her feel more in control. It’s a way of affirming that she can get what she wants (in one case, her preferred room in a shared apartment) because she’s lucky. And anytime things don’t work out, she reminds herself that she’s a lucky girl and that her mind-set will bring forth more of what she wants in the future.

Lucky Girl affirmations, and all the other hashtag affirmations, are a so-called way of hacking your thoughts and mind-set “to create your outer experience in the world.” Palazzolo says figuring out how her thoughts inform her reality and intervening in that process has proved to be hugely empowering, but also, it’s just fun. She was raised on Pinterest quotes and “all of those cheesy things,” and she is 18 years old: “I love to just imagine the wildest possibilities for myself — I’ve always been a dreamer.”

If you think you have heard this all before, it is because you definitely have. The idea that your reality is just a product of your thoughts and that you, the person with the mind and thoughts, are in control of all of it was made wildly popular by The Secret in 2006. The film turned book claimed to lay out “the secret” to a successful and prosperous life: the law of attraction. Regardless of what you might actually think of the law of attraction and the core tenets of The Secret, the film is a lot like a loud late-night infomercial that wakes you up in time to catch The Nanny. It bludgeons you upside the head with Billy Mays–style narration paired with B-roll of historic geniuses mumbling to themselves as they scribble down the secret. But Oprah was a huge fan and, according to the New York Times, The Secret was “a web and publishing phenomenon” that sold up to five movies a minute (including as downloads from the website and as DVDs). It was one of the first viral online trends, and another Times article noted that its core message could “best be understood as an advanced meme — a sort of intellectual virus — whose structure has evolved throughout history to optimally exploit a suite of weaknesses in the design of the human mind.” Damn.

The Secret’s popularity first took off in a post-9/11 America at the crest of the 2006 housing bubble. Airports were newly dangerous and people were losing their homes. Reality TV was wrapping up a decade of gritty true-to-life programming in favor of showcasing the lives of the rich and famous, from MTV Cribs to My Super Sweet 16. Similarly, the pandemic made us all desperate for even a semblance of power and control — and something, anything, that felt and looked good. This is when Manifestation TikTok took off. This is when the once-niche communities of the manifestation internet got flooded with an influx of hopefuls looking to change their circumstances and 2020 Google searches for “manifesting” went up 400 percent. And that need not only persists today, but has grown since: The cost-of-living crisis is tightening into a chokehold, and this is just while we wait for that looming recession shoe to drop.

Products like The Secret — and trends like Lucky Girl Syndrome — give the individual near absolute power (or, depending on whom you ask, the illusion of it) over the whole of their reality. It’s your mind, your world, make of it whatever you want. This is one of the reasons why Palazzolo, who watched The Secret when she was younger, is so inspired by Lucky Girl Syndrome: “Because it shows that I have control over my life and that I can be responsible for myself and do what I want.”

By far, the most prominent critique is how Lucky Girl Syndrome and the rest of Manifestation TikTok offer individualized solutions to systemic problems. Or that it doesn’t work. Some say it might even be dangerous and cause depression. Palazzolo knows it’s easy for her to be a dreamer and an optimist: “As a white female who has had pretty much every privilege possible,” she says, “it’s a lot easier for me to tap into these mind-sets and look at how abundant the world is, because that’s the world that I was born into.” But it’s those of us who are less privileged who have the most to gain by leaving this reality behind.

Before the Lucky Girl, there was the Delusional Girl: a TikTok trend from 2021 that mostly consisted of Black women encouraging each other to just “be delusional.” It’s perhaps not a stretch to see how, when your reality is so profoundly shaped by racism and sexism, it can be liberating to embrace delusion. As writer Chanté Joseph, who adopted Delusional Girl thinking last year, puts it, “Imagining an alternate reality where I am soaring despite the limitations of my identity feels like a respite.” Delusional Girls encourage delusion in life, work, and love. Kaylen Jackson went viral on TikTok for being an early adopter of the delusional mind-set. “To a realistic person,” the 23-year-old says, “believing in yourself is delusional, right? Believing anything can happen, that you can have everything that you want, that there is a secret cheat code to life where if you assume something, it will happen — that can be delusional.”

She likes the word “delusional,” she tells me, because it acknowledges that to most people, what she considers to be her natural optimism often sounds delusional. Her TikTok chronicles her adventures as a solo traveler who often enjoys whirlwind romances on her trips. “I get a lot of messages from people being like, ‘How are you not scared?’” and, she admits, “The way that I travel is delusional.” For Jackson, being delusional doesn’t take the form of an affirmation or mindfulness routine as is common on her side of the internet. She watches TED Talks, studies the lives of successful people (like Tom Brady and Emma Stone), and works to cultivate the “right” mind-set (one focused on abundance over scarcity). She admits she didn’t have the best grades in high school, but she refused to look into loans and instead, delusionally, applied for scholarships that could get her a full ride to college. “There was a point where my phone was just ringing off the hook every single day, a new scholarship each time, and I realized: It worked,” Jackson remembers. “And that was the first time where I was completely delusional.” She’s since credited her delusional thinking for her adventures in solo travel, exciting love life, and the ability to hold down a job that can fund these youthful escapades.

Another more out-there popular reality-shaping trend is reality-shifting. Reality-shifting is what clinical psychologist and researcher Dr. Eli Somer calls “a trendy mental activity” that involves transcending your current reality and moving your consciousness to your desired reality. The process looks different from shifter to shifter, but it generally consists of meditating or self-hypnotizing to the point where your consciousness travels to a totally different reality and therefore shifts from our current reality to your desired reality. Dr. Somer notes in his recently published paper in Current Psychology that interest in reality-shifting spiked just as the WHO declared COVID an “international emergency.”

In its early days on TikTok (around mid-2020), reality-shifting was something done by mostly young people who wanted to live in Hogwarts or the Marvel Universe — like fanfiction but more immersive. However, as the audience for this kind of reality-escaping content grew, and more people started adapting it, it has expanded to include not just megafans but regular people looking to add a new technique to their manifestation repertoire (although #ShiftTok is still mostly made up of teens and young adults). Reality-shifting uses affirmations and a range of self-hypnosis techniques to travel, some say through the multiverse, to another reality.

Reality-shifter Brianna Gorski admits she was first exposed to the idea of reality-shifting through Draco-Tok back in 2020. “But instead of shifting to Hogwarts, I can shift to where I’ve got this amazing life,” she explains. “I can use it to achieve my own manifestations.” For example, she has dreams of being a full-time content creator and told me this very interview was a product of her meditations. In order to shift, the 20-year-old student from Connecticut lies down in her bed. Then she meditates, repeating affirmations that help transport her to her desired reality (which varies from session to session). To help get her there, she might identify things from her desired reality that she can feel through each of her five senses. “And I’m also listening to music that makes me feel that kind of vibe.” Gorski’s routine is relatively simple; other shifters sometimes write out detailed scripts for exactly what their desired reality will look like: “People will script their parents, their family, their relationships, how much money they have,” Gorski explains.

Reality-shifting is notoriously difficult to accomplish, according to reality-shifters, but Gorski says she’s gotten incredibly close: “It feels like you’re falling but also going up at the same time. The best image I can give you is like when sci-fi movies, they have those beams of light that are just shooting up.” Coupled with manifestations and affirmation rituals, it’s the sum of all these practices that Gorski believes is able to actually push her life closer to her dream of “being a star or celebrity.”

For most shifters, reality-shifting is just one of many techniques they use to manage their minds. Sometimes they journal, sometimes they moodboard, sometimes they shift. The growing interest in these practices is a sign of our times, says Dr. Apryl Alexander, an associate professor of Public Health at the University of North Carolina Charlotte. “We’re really seeing the trend take off right now, after the last few years of what we’ve been through,” she says. And while a healthy level of concern and a critical understanding of these trends is key, Dr. Alexander tells me, “we struggle with nuance, and I really hate this ‘kids these days’ narrative.” More important than the fact “kids these days” are at odds with reality is the reason why. The last few years have been shaped by more than just COVID fallout: Local governments are criminalizing trans youth, Roe v. Wade has been overturned, and three months into 2023, America just passed the 100 mass-shootings mark. This is an exceptionally awful time to be young in America.

In his 2021 paper on reality-shifting, Dr. Somer compares the act to lucid dreaming and tulpamancy (which has a growing TikTok presence and a well-established Reddit footprint of over 44,000 on r/Tulpas, and involves creating distinct individuals, akin to imaginary friends, that live in your mind called tulpas.) The goal of the paper, Dr. Somer says, was simply to alert the scientific community of reality-shifting and to make an early attempt at describing what it is in terms clinical psychologists can study. While Dr. Somer coined the term “maladaptive daydreaming” in 2002 — when hours and hours of daydreaming keep a person from engaging with reality — he thinks reality-shifting falls under the broader category of immersive daydreaming. In other words, reality-shifting is not by definition unhealthy. “Basically, this is an extremely rewarding mental activity, because it enables people to have a virtual-reality machine in their mind in their head,” he tells me. “It’s easily accessible, it’s legal, it’s free. And it’s highly gratifying because they can direct their own story lines and their own lives and their own narratives.” Reality-shifting is unique, however, in that people who do it actually believe they are traveling through different realities, to which Dr. Somer says, “That is beyond science.”

It’s easy to gawk at these trends for how unrooted in reality they are — how simply they reject the present in favor of something else. How they create two realities: the real and the imagined, and how these two realities become mutually exclusive. And while caution is fair, public conversations are erring on the side of unfair moral panic: The youth-led Polyester Zine podcast recently wondered if this “adoption of pseudo-spiritualism may be more damaging than it first appears.” We’re also starting to see rising self-diagnoses for maladaptive daydreaming, perhaps an overpathologization of a newly popular, yet mostly harmless set of trendy mental activities. “It’s an attempt, particularly by younger people, to evoke joy and to imagine something different than the terrible spots we’ve been through in the last few years,” says Dr. Alexander, adding that “in a way, it’s adaptive.” And hardly ever maladaptive. Products like The Secret and these dizzying iterations of manifestation are what we reach for when we have limited options and imaginations when it comes to understanding and living through our desires. This is what it looks like to adapt and survive; it’s never ideal and often cringey.