When Colombian photographer Felipe Romero Beltrán met nine young Moroccan migrants in southern Spain, he felt a sense of kinship that led him to embark on a three-year-long project. Beltrán, a migrant himself, has long been disturbed by the oversimplified and often sensationalized images of immigrants portrayed in documentary photography. “You always see the tragic or the epic, where people are getting off boats or trying to survive in the cold,” Beltrán tells the Cut. “Documentary has this strong way of representing ‘the other’ in a way we know came from the last century, but we have to rethink it. We have to start once again from another point of view.”

His new book, Dialect, captures the agency of these young migrants, allowing them to express their identity on their own terms rather than as society often dictates it. The photographic series follows the group as they are held in state custody in Seville, Spain, a transit point for migrants crossing the Mediterranean Sea in search of legal status. (Undocumented and underage migrants are often detained by the state for up to three years while they wait for legal documentation.)

Beltrán first met the group at a theater workshop for immigrant social integration, where he was invited to speak about his own experiences as a migrant. Bogotá-born, he studied photography in Buenos Aires and lived in Israel and Palestine for two years before moving to Madrid to pursue a Ph.D. in photography. When he arrived, he was also undocumented. “I feel really close to them because we spent a good amount of time talking and sharing our thoughts and experiences,” Beltrán says. He’s currently in Mexico, where he’s working on an ongoing series titled Bravo.

As he spent more time with the group, he was in awe of their unique communication style, conveyed through their bodies. They projected an image of macho, muscular men that felt vastly different from his own physique, an observation that inspired Beltrán to name his project Dialect. In the images, some of which are staged, he uses the body as a striking metaphor for the journeys and state of limbo experienced by these individuals as they await the start of their new lives.

When he initially began photographing the guys, he was struck by their heroic energy. “They were really proud of being migrants and acquired this journey as an important and fundamental experience on their identity,” he says. However, over the past year, he has observed a shift in their self-presentation. They stopped speaking Arabic with one another, adopted a taste for Spanish and French trap music, and sported “fake Gucci or fake Balenciaga.”

Beltrán thought this signaled a desire to be seen as Spanish men rather than as migrants. “When I arrived in Spain, I changed my Colombian accent because, unconsciously, I wanted to integrate into society,” he says. “I didn’t want to be portrayed as the Colombian guy with all the implications a Colombian person has in Spain.”

In addition to the reenactments, which were largely led by the young migrants in Dialect’s images, Beltrán allowed them to decide how to pose, seeking to capture them the way they want to be seen. As a result, we’re offered unguarded moments and an unfiltered peek into their lives — from bleaching their hair to working out to even the raw intimacy of photographic subject Bilal Siasse smoking a cigarette while holding a mirror for Youssef Elhafidi as he pops a zit.

Beltrán even swapped out his usual film camera with a digital one so he could show them the images as they’re being taken; if they didn’t like them, he would discard them. “I can’t be so naïve and say that I portray them as they wanted to be portrayed a hundred percent, because it’s my way of seeing,” he says. As the photographer, he made decisions about lighting, framing, and composition. And while the group had significant input on posing, Beltrán selected what would appear in the book. For instance, when they wanted to pose with fake guns, he snapped the shot but refused to publish it, as he felt a responsibility to protect them. “I’m not showing this because you don’t know the implication it has of you as migrants or me as a Colombian,” he explained to them.

Regardless, Beltrán accepts that he cannot control how others perceive his images. “The viewer is a complicated concept that, honestly, I don’t think about,” he says. He’s more mindful of the power dynamics at play as a storyteller. “If I were a guy from Spain or Colombia with a certain privilege, the relationship would be different. But at the same time, I have the privilege to be educated and to have a camera,” he says, still noting that he wants to maintain a balance of perspectives.

Looking back, Beltrán acknowledges the thematic elements he’d overlooked. “I was completely unaware of this sacred religiousness on the project,” he says. Perhaps it’s Seville that gives rise to this feeling; with a potent Catholic influence and a rich religious history, the city exudes an atmosphere of deep devotion and reverence. “It influenced me, but also the guys who came from an iconoclastic culture,” he says. One photograph that stands out to Beltrán as a favorite is a spiritual reenactment of their journey to Spain, when Siasse’s friends carried his body after he fainted. The group together in communal support, holding each other up and bearing one another’s burdens.

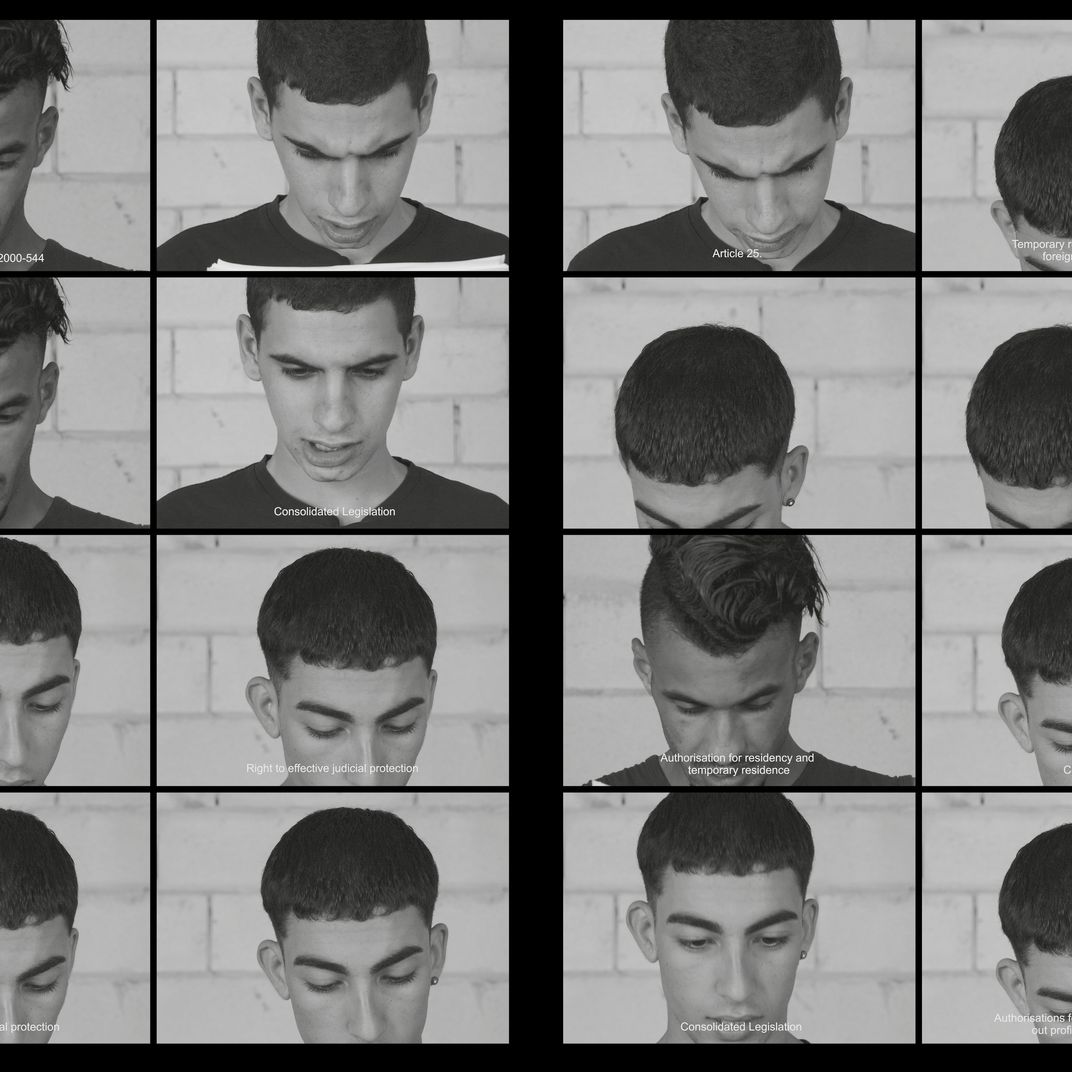

Beltrán also put together a video installation that underscored the political layer of the project; he included some stills in the book. The video features three of the migrants reading the first four pages of Spanish immigration law. “It takes 20 minutes to read, so you can see how they struggle with the actual document that defines them and defines me as a migrant myself,” he says.

He also incorporated stills from his other collaborative project, Instruction. The frames show Siasse performing a choreographed routine alongside choreographer Lucia You, in which he symbolically guides her through movement on the Spanish frontier. “The piece, from my side, is a process of this failure or impossibility to teach someone how to cross the border,” he says. “It also has moments of conversation, because it shows how impossible it is to make a representation of that.”

Dialect is accompanied by six interdisciplinary texts, including contributions from a physicist explaining how boats endure this treacherous journey. Additionally, a choreographer, a philosopher, and an anthropologist specializing in migration offered their perspectives. Finally, two of the featured migrants, Elhafidi and Zakaria Mourachid, contributed their own written pieces.

In Mourachid’s opening note, he writes, “This is the story of a Moroccan guy born in Casablanca, on October 26, 2001. It is a life story that is still in process, but that in the past 21 years has had many changes and has made our guy learn and radically change his way of thinking and seeing the world, a world that is sometimes more unfair and difficult for some. This is a story of overcoming, strength, courage and heart.”

Dialect, by Felipe Romero Beltrán, is published by Loose Joints.