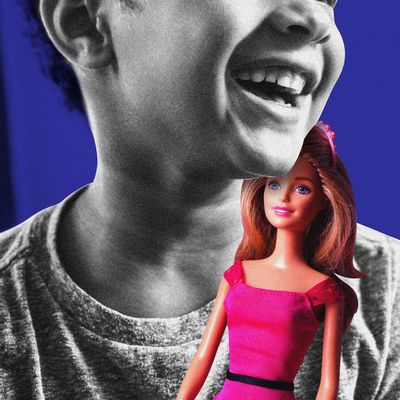

The drawers in my childhood bedroom were painted with red, glossy paint. The shiny red shade I had chosen was like Dorothy’s red slippers. Dust sometimes gathered on the uneven surface where the paint had clung to the coats that came before, temporarily muting its sheen. The top right-hand drawer was where I kept my most treasured possessions: my Barbie dolls.

I was around 5 when my mother took me to get my first Barbie. I remember the excitement of walking through the toy shop, past lots of other toys little boys like me would have been expected to prefer, before running my hands through Barbie’s gorgeous blonde hair. I squeezed her so hard that she would have suffocated if she had lungs.

Next came Mermaid Barbie, who was my favorite. Like Ariel in The Little Mermaid, she had flaming red hair and a dazzling, shiny green tail. Just before bed, I would ask my mother if there was any chance I might become a mermaid someday. She always let me down gently, but I still remember squeezing my eyes shut really hard and wishing that I would wake up with a fish tail the following morning. (In hindsight, that would have been pretty traumatic.)

This summer, the aggressively pink promotional campaign for Barbie — the first live-action film based on Mattel’s iconic 1959 plastic doll, directed by Greta Gerwig — has been inescapable. Posters for the film are everywhere, and befittingly for a movie based on a product, there is hardly a brand or celebrity who hasn’t secured a sponsorship deal. The film’s lead, Margot Robbie, appeared on the cover of Vogue, and a life-size version of Barbie’s palatial Dreamhouse popped up in Malibu. (Available to rent via Airbnb, of course.) In London, where I live, bizarre monuments like a pink TARDIS appeared across the city ahead of the premiere.

It has been surreal to see a doll that I used to keep secret in my bedroom, because I didn’t want them to be seen by just anyone, become an object of intense fixation by pretty much everyone. One time, my worst fear materialized when a friend found my Barbies in the drawer during a playdate. I tried to find an explanation for why they were there that would make it clear they weren’t mine. That’s the thing about gender norms: They can convince young children that lying about things which bring them joy is not only acceptable, but the right thing to do.

As a 30-year-old gay man, I’ve met a lot of other queer people who also hid parts of themselves in childhood. Experimenting with femininity in the safety of the home — even something as minuscule as selecting girl characters in video games and living vicariously through her ability to kick ass — seems to be a shared gay experience for many of us.

None of this makes a person gay, of course. I’m sure there are heterosexual men who sometimes played with toys that, at the time, were aimed at girls. But the lure of femininity was a bigger release for me: It was about becoming someone else. On weekends, I’d raid the dress-up box and pretend I was a Spice Girl, or wear a plastic tiara to become Princess Diana. I had a pair of sparkly fairy wings and I’d wear nail polish in all different colors, which was scrubbed off on Sunday nights to remove any trace of it before school, reinforcing a feeling of rebelliousness.

It might sound strange to position Barbies as part of my subversion of gender norms as a child. I must have been around 8 years old when a girl in my class said that a real-life Barbie wouldn’t be able to stand up properly because of her body’s impossible proportions. It’s not like Barbie is known for being inclusive, either: It wasn’t until 2016 that Mattel released its first-ever lesbian Barbie, and historically they have been overwhelmingly white and blonde. Alongside Robbie and Ryan Gosling, Gerwig’s film features more diverse Barbies (Issa Rae, Hari Nef, Ritu Arya) and Kens (Ncuti Gatwa, Simu Liu), which reflects that Mattel’s dolls have become more varied in recent years. But the overarching legacy of Barbie is still one that has reinforced white-centric and unattainable body norms.

It may seem counterintuitive, but when you’re told that enjoying anything feminine is wrong, playing with dolls that represent the most pristine and saturated version of femininity can feel subversive — even if that doesn’t erase Barbie’s other sins. It feels reminiscent of the adoration that gay fans hold toward old Hollywood beauties like Joan Crawford and Judy Garland, or the pageant-style exaggerations of femininity that underpinned so much of early drag culture. Barbie has been the subject of the same gay diva worship over the years, and Gerwig’s film prominently featuring LGBTQ+ actors feels like a nod to that history.

Part of Barbie’s gay appeal might be that, despite being plastic and unmalleable, she can transform herself into anything: doctor, lawyer, judge, journalist, and vet, or whatever Mattel thinks will sell the most dolls. (America has never elected a female president, but Barbie has held that job for years.) As the world’s most famous doll, she has been cast as both an aspirational hero and a reductive villain — in the gay world, this polarizing duality often turns women into icons.

After I came out as gay, I spent a lot of my younger adult life recoiling when people said that they “already knew.” That well-meaning comment sometimes made me feel like everyone was in on the joke except me — and foolish for ever feeling conflicted and nervous about coming out. I hated looking at pictures of myself as a child, or watching home videos, because that same joke was lingering in every frame. But watching fans and even film critics stanning a movie as loudly feminine as Barbie has made me realize how much of that shame I’ve since relinquished. The fan “war” between Barbie and Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer — a film released on the same day with a moodier, darker vibe — is validation that it’s okay to be excited about something so transparently fun. Now, I feel proud of my little gay self for having the courage to play with those fabulous dolls — and of my parents for buying me the toys I wanted, not the ones I was supposed to like.

I hope it’s no longer such a taboo for boys to find joy in femininity, whomever they turn out to be, and that less energy is expended on making children fit in with conventional, adult visions of what they should enjoy. Barbie has a complicated legacy, but to me she represented the possibility of happiness and transformation. For children like me who didn’t always fit in, that fantasy was worth clinging on to — and keeping safe at the back of a drawer.