The year Deb Roberts turned 40, she felt like the universe was sending her signals to have a baby. She always knew she wanted to be a mother, but she’d been waiting to find the right guy, get married, and be more financially stable. As she watched her friends have kids or freeze their embryos, she thought she had time. Then she went to a wedding and met a fertility doctor who told her if she wanted to have a baby, she’d better do it soon. “You don’t have a minute to waste,” she remembers him saying. She broke up with her then-boyfriend, who had three children from a previous relationship and didn’t want any more. She consulted fertility experts, took hormones, harvested her own eggs, and bought donor sperm. She was ready.

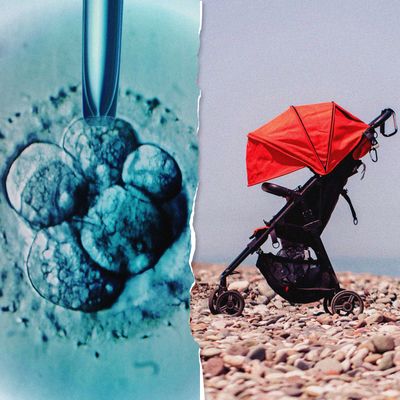

But then the eggs failed to fertilize. So she tried again. And then again. She spent $100,000 on IVF, which ballooned to $140,000, then she stopped counting. “It was the longest three and a half years of my life,” she says. After harvesting more than 180 of her own eggs, Roberts ended up with one viable embryo, which she miscarried. She couldn’t afford to buy donor eggs and go through the entire IVF process again. She signed up to adopt, but the process was dragging on with no child in sight. Then she heard about embryo donation, in which people donate embryos left over from IVF to others trying to start families. Embryos are human tissue and illegal to sell, so the process is much more affordable than egg and sperm donation, hiring a surrogate, or even adopting.

Roberts contacted Snowflakes, the oldest embryo-matching service in the U.S. But as a Jewish single woman, she was unlikely to be a top choice for many Snowflakes donors, who are predominantly Christian and prefer to place their embryos with married couples. And because Snowflakes accepts all embryos, including those that are less likely to successfully develop into a child, Roberts worried she would end up miscarrying and be heartbroken again. Another organization, the National Embryo Donation Center, refused to work with her because she is unmarried. “They have all these criteria for who they think are perfect parents,” she says, and she didn’t make the cut.

In desperation, she posted on Facebook. “It’s simple: I want to be a mom,” she wrote, asking to connect with women who had extra embryos or with pregnant women who would be interested in discussing adoption. Friends and strangers from around the world wrote to her offering their embryos. Finally, in 2017, Roberts gave birth to her son, Sam, and two years later, to his sister, Brie. The children are genetic siblings, both embryos donated by a friend.

The experience of becoming a mother was transformative for Roberts. She’d been working in corporate marketing, but now she had gained a wealth of knowledge about how to navigate all the legal, medical, and logistical challenges of embryo donation. She started her own matching service called Embryo Connections, hoping that a more welcoming, nondenominational service would make embryo donation more accessible. Like a traditional matchmaker, she compares families’ interests, hobbies, and values. “I take it so seriously because these are families that are going to spend the rest of their lives connected in some way,” she says. She sees embryo donations as gifts of possibility. “It’s giving people the cells that they need to create a life,” she says.

As with so many other reproductive issues, talking about embryos can be sticky. Depending on your religious and political beliefs, these fertilized eggs are human tissue, or they’re children; they’re property, or they’re people. Over the past three decades, conservative activists have relabeled embryo donations as adoptions in an effort to further the idea that life begins at conception. While Roberts never uses that term, she recognizes that embryo donation is not a straightforward property exchange. After all, there’s a 50 percent chance a child will be born at the end of her matching process. This murkiness between donation and adoption, between embryos as possibilities and embryos as children, is something scholars, doctors, and families participating in embryo exchanges all must navigate.

The number of embryos in storage has dramatically risen as IVF has become more popular and more successful over the past four decades. There are no limits on how long embryos can remain in storage and no limits on how many embryos a person creates. By some estimates, there are now between 2 and 5 million frozen embryos in the U.S. Conservative Christian organizations have dominated embryo exchanges since the mid-1990s, and these groups call the exchanges adoptions and treat them as such, even requiring costly home inspections for potential parents. “I don’t see it as any different than me adopting a baby that’s already been born,” says Kimberly Tyson, vice-president of the Snowflakes Embryo Adoption Program. These groups alienate or outright exclude many prospective families who don’t fit their model for parenthood. Recipients in these programs must have been assigned female at birth and apply before they turn 45, while couples must have been married for at least two years. Snowflakes works with families of all faiths, married LGBTQ families, and with single parents, but Tyson says that it can take longer for non-Christian and single or LGBTQ parents to find a couple willing to donate to them. At NEDC, there are also weight requirements for embryo recipients.

Although the first embryo donation in the U.S. happened in 1984, it took more than a decade for conservative Christians to seize on the idea that embryos are people. In the mid-1990s, John and Marlene Strege, a Christian couple in California, were desperately trying to have a baby. The Streges saw embryos as “preborn” children and refused to consider donation. “You donate money, food, clothing, and time but you don’t donate life,” John wrote in a subsequent memoir. Working with the Nightlight Christian Adoption agency, the couple instead arranged to “adopt” an embryo. They followed California’s adoption requirements, including a home visit and FBI screening for the family giving the embryo. In 1998, they had their daughter, Hannah, whom they call a “snowflake” baby in honor of her frosty origins. The Nightlight Christian Adoption agency then took the name Snowflakes for their embryo-adoption division, and conservative Christian activists began to talk about surplus embryos as children trapped in frozen orphanages.

Conservative activists have kept up that intensity in talking about frozen embryos in recent years. In the Supreme Court case that overturned Roe v. Wade, lawyers filed an amicus brief on behalf of the Streges that compares the state of frozen embryos to that of enslaved people in the 19th century. In turn, doctors and medical associations have changed how they talk about embryo donation. While in the early days of IVF, the technology’s pioneers referred to the possibility of exchanging embryos as “prenatal adoptions,” the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) is now adamant that embryo donation is a medical procedure. “Any attempt to make it more than that is driven by politics and the desire to inflate the legal and moral status of the fertilized egg in the interest of stopping abortion,” says Sean Tipton, chief policy officer at ASRM. Risa Cromer, an anthropologist at Purdue who studies embryo donation, says the political or social treatment of unborn embryos as children has major repercussions. She cautions that language creep could impact other kinds of care: Fetal-personhood arguments could not only lead to more abortion restrictions, but also provide a foundation for laws that consider common IVF practices, like selectively eliminating embryos and disposing of surplus embryos, to be murder. Even so, ASRM’s ethics statement acknowledges embryos have a “special significance” that make them different from sperm or eggs. Seventy percent of embryos will never develop into human beings, but these tiny clusters of cells carry with them a huge potential — to become people, children, family.

Though embryo-donation rates remain low relative to other technologies like traditional IVF, it’s becoming more common. According to a 2023 study in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, between 2004 and 2019, annual embryo-donation rates more than tripled from 666 to 2,492. Cromer attributes some of that increase to the emergence of nondenominational Facebook groups and matching services like Embryo Connections.

Schuyler Dayhoof, who lives in New Hampshire and describes herself as pro-choice, says that Embryo Connection’s inclusivity is the reason she chose to donate her embryos through its matching service. Dayhoof and her husband had eight surplus embryos after having two children through IVF. Even though Dayhoof never considered those embryos her children, she felt she couldn’t dispose of them. Especially not after having experienced the heartbreak of infertility and the joy of finally having kids. “I don’t believe that an embryo is a life,” she says. “But it still felt funny destroying that possibility of a baby for somebody.” Dayhoof has donated her embryos to two families so far.

Since the Streges, a lot of the best practices around embryo donation have grown to resemble the adoption process. Roberts can’t ensure anonymity for donors because of the proliferation of genetic databases like 23andMe. Although she doesn’t require home visits, she does require that donors provide a medical history and contact information so that their genetic children can reach them, if they choose to, after they turn 18. Ruth, who asked to be identified by her middle name for privacy, had two children after being matched through Embryo Connections. She’s thankful she had Roberts’s guidance in navigating her relationship with her donors. While Ruth wanted her kids to be able to get in touch with their genetic siblings, she worried they would feel pressured to connect with this other family or that the donors would want too much contact. Roberts counseled her to keep in touch in case a medical emergency or a question about family medical history arose, and showed Ruth an online portal that allows families to connect without having to divulge their email or home addresses. The families have used the Donor Sibling Registry to send pictures and messages over the past three years and grown closer than Ruth expected. “The donor couple is so lovely,” she says. Soon, she thinks, she’ll be ready to give them her phone number and email address.

Roberts may have worked with around 800 families since starting Embryo Connections in 2018, but she’s still grappling with one of the stickier aspects of the process herself. When Roberts’s friend first offered her embryos, she imagined they’d raise their respective kids like cousins. But life intervened. Roberts and her donor are both working single moms living in different states. When Roberts does travel with her kids, they usually head to Florida to see her parents. “You can’t tell a grandparent you’re not gonna go see them,” she says. While Roberts wants her kids to know their genetic siblings, she realizes it’s ultimately going to be up to the now 3- and 5-year-olds to decide whether they want to have that relationship. She’s always been honest with them that she isn’t their genetic mother. That’s a fuzzy concept for children who are still playing T-ball, and as far as they’re concerned, she’s just Mom. After all, she’s the one who carried them and birthed them. “From inception in utero it was me: my voice, my smells, me,” she says. “I’m the only mom.”