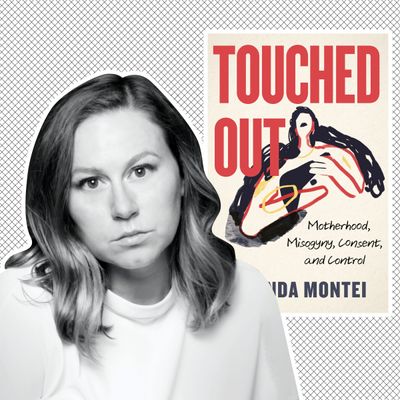

Amanda Montei’s Touched Out: Motherhood, Misogyny, Consent, and Control starts with a sledgehammer. “I sometimes imagine there is one forgotten trauma,” Montei writes in her latest nonfiction work, “one moment in my youth, when I started to unstitch from the center, but the beginning of a body is untraceable, even if, in America, we are always trying to start ours from scratch.”

The unstitching that Montei goes on to describe in this memoir-meets-culture criticism — influenced directly by her observations of her own mother, her interactions with boys and men, and the gender roles assumed by her and her partner as they stumble into parenthood — can in fact be traced to much larger sociocultural and political forces, and Montei draws these lines well. And in a rare feat for a writer so adept with theory, she illustrates these forces with so much intimacy and vulnerability that the reader cannot help but begin to see them in the shadows of her own home, her own body. In Montei’s pages, we traverse from activist Silvia Federici’s “wages for housework” campaign to the isolated slog of caring for a newborn baby constantly tugging at Montei’s breast; from dismissive doctors and the normalization of maternal suffering to late-night wine-chugging and frantic Google searches for a solution to the unsustainability of modern parenting; from the overtures of her husband to the high-school parties where Montei first learned to subsume her body’s needs in service of boys.

The term “touched out” has come to signify the idea that when mothers have young children pawing at them all day, they recoil from other physical contact, such as sex. Montei has been building a maternal uprising with her Mad Woman newsletter and her writing on the death of parenting advice, and she uses the backdrop of patriarchy to take the “touched out” concept to new heights. “The book is really about motherhood after Me Too,” Montei says. “And the connections between rape culture and the institution of motherhood, the continuity between these two kind of cultural institutions and the way that they see women’s bodies. But then personally, it’s a story of moving through those institutions myself.” “Motherhood feels like a script written by men for women,” Montei writes, “because it is.”

I burned through the pages of Touched Out like it was a whodunit — the crime scene consisting of women like Montei and myself, shell-shocked by motherhood and confused and ashamed about such a response. I yearned to go back to my younger self and hand her a copy. “I wish someone would have told me, ‘When you have a child, you are going to evaluate your entire sexual life,’” Montei says. “‘You’re going to want to unpack the entire institution of marriage and notice that your feminist husband has masculinity deep inside him just like any other man. And your ambitions will be hemmed down because of your child-care options.’”

After watching me carry the book around our apartment like a talisman for days, underlining paragraphs and muttering little “amens” under my breath, my 5-year-old daughter asked, “Why are you always reading that book instead of helping your kids?” I told her, not without some anxiety for the ways her future was implicated, that if she read it, she would understand.

A few weeks ago, I met Montei at a café across from the community arts center that gave her her first postpartum job. We were deep in the suburban sprawl east of Oakland — with its lonely reverence of consumerism and nuclear families — which is the aching backdrop for so many scenes of early motherhood in Touched Out. Despite the operatic soundtrack being pumped out onto the sidewalk, we were able to get into motherhood, sex, and the myth of choice for American women.

First things first: Should my husband read this book?

Why shouldn’t he? We don’t ask that question about male authors, we just presume that what they’re writing is for a universal audience. I didn’t write this book for men, and that shouldn’t prevent them from reading it or imply that it’s not worthy of male attention.

This could have been a much less personal book — an “idea” book. Why was it important for you to put yourself in it?

It started primarily as a memoir, with a weave of some cultural literary theory. And then the pandemic happened, and it became a lot more urgent for me to be more in the book, but also to include more cultural history to answer the question, How did we get here? And I think I was back in that place of early motherhood, where the body is just wrecked, and so that became a much bigger focus of the book as a result.

It’s hard to write a book that really catches the wave of the Zeitgeist. Did you know that you were writing a book that was highly timely? Do you think we’re ready for this book?

I was already thinking about a lot of these ideas, but then suddenly during the pandemic people were talking about these previously very radical feminist concepts like paying women for housework, which prior to then was considered really out there. But I think your question of “Are we ready for this?” is also a question that I asked because it’s still somehow dangerous to talk about sex and sexuality and assault and violation next to motherhood.

How did you manage to write a book in a pandemic while parenting two young children?

I had the feeling that I think a lot of women writers at the time had: “I’m stuck.” Because I only had so much time in the day to work on it. And so that was really agonizing. But then I got a child-care tax credit and I got unemployment and I decided I’m gonna use that to write this book.

Like a micro-experiment of paying women for child care.

Right? I squirreled that money away, and then when we did finally go back, I worked less, and I kind of paid myself to do this project.

You describe some pretty harrowing moments from your sexual past in Touched Out. How did you take care of yourself during the writing process?

When I first started, there was a lot of shame I was carrying, not just around early sexual experiences but around, like, I don’t want to have sex. I want something different. What am I mad about? Why am I resentful? Being able to articulate that is something that I hope is illuminating for readers, but also for me as an author, I have a lot more clarity that’s allowed me to understand how to make these institutions — like marriage — less filled with shame.

It was this excavation process I felt like I had to do, and then moving through that really led me to get sober, and that’s how I did, and still do, take care of myself. I used drinking to make myself that ideal mother. I was that ideal mother all day and then I would numb out at night. And then I realized that I was disappearing myself, turning myself into this backdrop for my children’s lives. There was a lot of stuff that was getting buried, and I really didn’t want to do that anymore.

Being “touched out” had always been presented to me before as something that could be solved with a little time, patience, and womanly stick-to-it-iveness. But one of the things I value most about this book is how you don’t give us an easy way out. How do you reconcile the fact that the forces you describe are so large and inescapable, but individuals still want change, pleasure, and agency?

It was really important to me not to provide a set of simple solutions and end this on a false-empowerment note. I think this book is precisely about that feeling of, How do we escape these very large forces that have to some degree become part of us? So for me the project of the book was to walk a reader through that experience of trying to figure out where is the self in all this? And where is my body in all of this? There is a bit of a recovery narrative at the end; that’s my story. But it’s an individualistic answer to all of the larger problems that are explored in the book.

There was a while where I was like, How do I end this book? Do I blow up my life? And what would be the alternative? A return to some kind of easy marital relationship or some kind of sexual awakening? Not every memoir is gonna be an inspirational character. Sometimes we’re just people processing our lives and creating an aesthetic object out of it.

I do talk about some of the things that we obviously need so that parenting doesn’t feel so exploitative — basic income, child care, health care, social services, work-reentry programs. But it was really important to me to resist the trend to turn memoir into self-help.

In the book, you make a distinction between the neutral act of raising children in a vacuum and the very culturally bound act of mothering in America. You ask of American motherhood, “Did I really consent to this?” What would consenting to motherhood actually look like for women?

Well, first of all, reproductive autonomy. But part of what I want to explore is not just motherhood, but how we’ve consented to the conditions of our lives in subsequent years. It’s a question of agency, which makes people super uncomfortable, right? Because they want to believe in this concept of free will. But that’s never been the case in American life. Agency has always been conditioned along the lines of gender and class and race, and what state you live in, or sexual identity.

I thought about my children a lot reading this book — we each have a son and a daughter — was there any part of writing the book that gave you hope or clarity around how this all gets handed down?

I’ve been able to let go, somewhat, of the belief that the burden is on me to teach my children the right way to think about everything. I emphasize bodily autonomy and consent; that’s sort of the foundation of how I think about parenting. As my kids have gotten older, there’s a lot that’s not in my control. And writing this book really confronted me with that fact. It’s a major source of loss, especially for women, as your kids go out into a world that disempowers you. That’s not without pain, but it’s also sort of liberating to work to let your children make their own way, and know that you’re in conversation with them. That is parenting to me.

How has it been to write about your partner and family?

Women authors who write about their children get this question. What about your kids? How are they gonna feel one day? It gets at this expectation that women showing up wholly as ourselves will somehow damage the people around us. We have to subsume ourselves into the men and the children, and be self-effacing figures in order to be good. That does bleed into some of the questions of, but how are you going to get away with this? But why wouldn’t it be okay to write honestly about your life? If the truth is dangerous, then it seems all the more important to write.