It’s 2017. The 20-somethings milling about Soho are wearing “The Future Is Female” T-shirts and coveting a membership in the women’s-only co-working space the Wing. They carry pink Bubble Wrap pouches inside their Madewell work totes, where they store a pomade that helps them achieve bushy eyebrows to rival Cara Delevingne’s. And their boyfriends know exactly where they got that little tube; they may have even stood in a long line outside Glossier’s neighborhood showroom with them to get it. Glossier “transcended the beauty niche,” journalist Marisa Meltzer says, and it had a choke hold on the public like no other (equally financially successful) brand in the 2010s. After all, Timothée Chalamet was spotted wearing a Glossier-branded hoodie — not merch from Drunk Elephant, Tatcha, or Charlotte Tilbury.

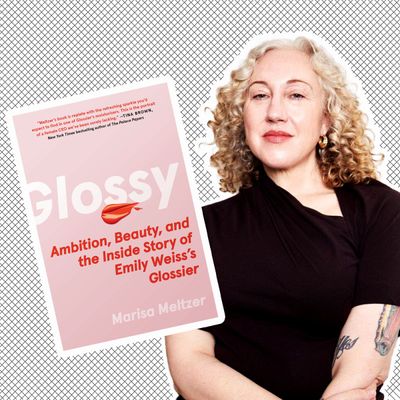

In her new book, Glossy: Ambition, Beauty, and the Inside Story of Emily Weiss’s Glossier, Meltzer argues that the company’s success was never really about its cult-favorite products. Instead, it was about the image of femininity that those products sold: chill, carefree, and natural. “But like the labor of applying makeup to make you look naturally beautiful, nothing about Glossier is effortless,” she writes — least of all its founder, Emily Weiss, whose ambition was clear from her first appearance as the hypercompetent Teen Vogue “superintern” on MTV’s mid-aughts reality show The Hills (a rewatch makes for an excellent pairing with the book). “I’d never seen anything like it,” Meltzer writes about the “born networker” who learned how power worked in the fashion and beauty industries by sitting on insiders’ toilet seats and rifling through their medicine cabinets for her first venture, the beauty website Into the Gloss.

Meltzer vividly reconstructs how Weiss’s ambition propelled Glossier’s birth and rise, and what she’s unable to pull out of Weiss herself — the founder stonewalls during their sit-down interviews — she makes up for with behind-the-scenes anecdotes. Weiss surreptitiously takes the office hand towel home and washes it every night, implements a draconian “no mess” desk policy at Glossier headquarters, and delivers intense monologues about being a woman in tech to candidates interviewing with her for a job. These details add to the portrait of a woman who’d been branded by the media for years as the epitome of cool, yet whom colleagues often found awkward; who modeled herself on blowhard tech-bro founders, yet downplayed her skills and achievements; and who ultimately managed to step down from the company on what appeared to be her own terms, rather than going out in flames like many girlboss-era peers. The Glossier of 2023 is no longer quite as popular or ubiquitous, and it must figure out where it goes without its figurehead.

Weiss is a very guarded subject, even with you, someone who has interviewed her many times over the years. How did you approach reporting about someone like that?

She’s a bit of a cipher, which I appreciate, but it’s hard for writing a book. The best thing I could do was to refuse to simplify her, or the company, or the time. In my writing, if I’m at a crossroads or if I’m feeling like a situation is complicated, I find it’s best to lean into that and talk about that conflict.

Emily Weiss is someone who is very hard to know. I didn’t speak to her parents, and I’m sure they feel that they know her well. But I don’t know that there’s anyone I spoke to who didn’t profess the feeling of her being unknowable and hard to read. This is fascinating when you factor in her propensity for being really emotional at times and crying a lot. The only other people I know who cry like that are actors, whose whole job is to easily access their emotions. Many people I’ve interviewed have reported her crying, and so you start to wonder, is this a tactic or is she a person who is constantly super vulnerable?

This was also puzzling! She cries frequently. She reveals fairly private bits about herself, such as the process of freezing her eggs. She posts very candid photos of her daughter’s birth (placenta included) on Instagram. But at the same time, the way she speaks about herself often feels surface-level, and the way she behaves feels canned.

If I’m being generous, I would say she was often really overwhelmed. And that was probably how she dealt with big emotions — swinging between wanting no one to know anything about her and wanting people to understand that she was human and just like them.

If I’m being less generous, I would say that it was all a little bit of a role — like the way she stopped bleaching her hair platinum and stopped going to fashion shows and started wearing pants suits, inviting business people like Disney CEO Bob Iger for fireside chats, speaking in business speak, investing in other companies, and talking about being interested in longevity.

The book can also be seen as a story of this theater kid evolving into different roles in her life: reality-show and downtown ingénue, then girlboss makeover, then this sort of founder-philosopher, and then someone who has to deal with real challenges for the first time.

What struck me about the book was how distinctly American Weiss’s story is. She is privileged to begin with and catapults to business fame without any real credentials, just pure drive. Is her story the true American Dream?

It’s a very American story on every level. This is her real first job, and within five years of launching, the company is worth a billion dollars. But if you dig deeper, you realize it helps if you come from a family that presumably can pay for you while you do all these internships or low-paid jobs, and you can make the right connections, and you’re pretty and thin, and you have great clothes. That’s how America really works. That’s how people tend to get ahead.

Weiss would deflect from answering questions or suddenly take your conversations off the record, which you say was very frustrating. What did you not ask her that you would want to know?

I don’t usually hold back in terms of asking things. I’ve asked her about her divorce, I’ve asked her about stepping down. That’s not the problem. The problem is that she never answered me in a very satisfying way. I would have loved to have a timeline of her emotions as the CEO of Glossier. At what point did she start thinking, Maybe I want to step down? Was it because she was thinking about other things she wanted to do? Was it because she wanted work-life balance? Was it because she was just like, “I don’t want to deal with supply-chain and shipping issues and packaging minutiae?” She wasn’t willing to let me in on that process. She did not like being written about and was going to give me as little as she could get away with.

You also pose that her inscrutability might have shielded her from an epic fall, like those of her girlboss peers Miki Agrawal of Thinx, Audrey Gelman of the Wing, or Leandra Medine of Man Repeller.

When you’re not giving that much of yourself, it’s much harder to attack you or to bring you down. Which is probably why a lot of the charges against Glossier were not so much about her, but more about the company and the system and the way that employees were treated, particularly in retail spaces.

Glossier gets lumped in with the other girlboss businesses. And yet what emerges from your book is that it seems to have handled the pandemic and the racial reckonings of 2020 more adeptly than many other companies — for instance, keeping retail employees (“offline editors” in company parlance) on payroll longer, offering them furlough and severance.

I think it’s unfair to all of them. Glossier seems to have done a lot better than a lot of companies that are owned by multibillion-dollar conglomerates. This is a relatively small company. It’s a young company. They’re facing truly unexpected and unnavigated territory. I do think they were trying to do right in the pandemic. They’re imperfect. But it was important to show when I thought Glossier deserves credit, when Emily Weiss deserved credit, when they did things well, and when they were innovative.

You quote the classic Janet Malcolm description of journalism as an act of preying on people and betraying them. You also write about grappling with how not to be an invasive asshole and at the same time do your job. There was an extra level of trickiness here because you were scrutinizing a young female founder. How did you think about striking a balance?

The most feminist thing I could do is not think about her gender in terms of how I was going to write about her and just tell her story in all its complications. The problem of the myth of the girlboss, or part of it, is this idea of a picture-perfect ascendance. I’m posing on the cover of a magazine. I’m in my beautiful, Instagrammable office. I’m with my cool, famous, or rich friends. I’m with my perfect husband and dog. I’m at my country house. I’m ringing a stock-market bell. Or whatever. There’s not a lot of nuance in that. I think that’s part of why people have a lot of glee at taking those women down a little bit. Whether or not they wanted to be put forward that way, it’s easy to resent them.

What is the biggest misconception about Glossier?

That Glossier is a beauty company that you don’t need to know about unless you’re a young woman. The business story of Glossier, and the story of Emily, transcends just being for someone who already knows about it or is interested in makeup. Men — and I’m saying cis white straight men, obviously — are so used to this idea that male culture is culture. I hope it’s changing? But it’s going to be gradual. You know, men are going to Taylor Swift, men are going to Barbie. They’re kind of getting congratulated for that, where it’s like, Oh, cool. You love A+, high-quality entertainment. With this, it’s like, Oh, you want to read a gripping story about a fascinating woman and a company that is worth $1.8 billion? I do hope they read it, because it is not just a story about a girlboss. Hopefully, we can start to move away from that.