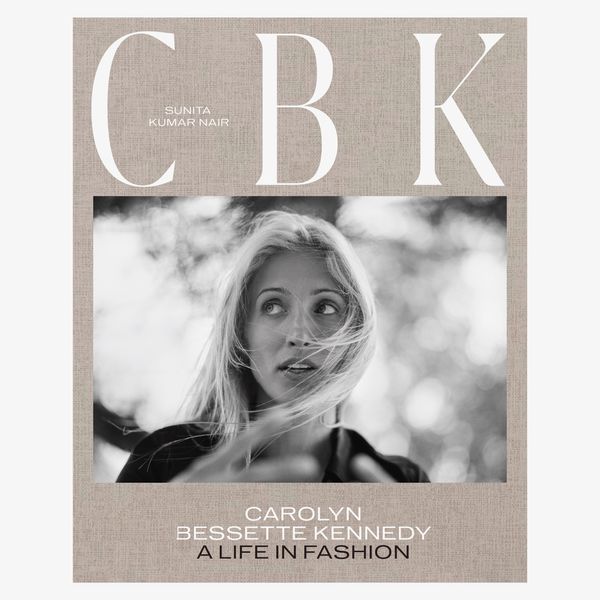

In her new book, CBK: Carolyn Bessette Kennedy: A Life in Fashion, Sunita Kumar Nair explores the enduring appeal of Bessette Kennedy’s style. This excerpt taken from the book shows how she is the style blueprint for minimalist brands from Jil Sander to Bottega Veneta.

By July 1999 she was gone.

That was then — this is now.

Her silent-movie presence intrigued film directors and actresses alike; Carolyn Bessette Kennedy became the ideal for all that was considered class — too patrician — and of a distant elegance. David Fincher, the director of the music video “Freedom! ’90,” by George Michael, coincidentally included some of Carolyn’s model comrades from her CK days — Linda Evangelista and Christy Turlington — who were now trademarked as “supermodels,” thanks to this trailblazing film, which also became a fashion anthem for that decade. Fifteen years on, for his thriller Gone Girl, he advised his leading lady Rosamund Pike to study Carolyn for her main character. He compared Pike to an orchid, not like the other flowers on the lawn, an only child who just did her own thing. Actress Robin Wright’s team on House of Cards perpetually looked to Carolyn’s understated fashion for her role, and with the backdrop of the White House, there were obvious parallels between reality and fantasy. Carolyn’s signature looks were again literally translated with contemporary designers like Toteme, Khaite, The Row, and Céline. In the series Anatomy of a Scandal, Sienna Miller’s character, Sophie, is desperate to keep her world contained, to present a stoicism as her apparently perfect world disintegrated; her wardrobe is the perfect foil for her internal despair. Whatever the interpretations made of Carolyn — direct or indirect on film — it was clear that her mystery and aloofness, her suit of armor, was enough of a canvas for these artists to draw on for their parts.

On social media, John Jr. and Carolyn’s photos are repeatedly used to represent tokens of taste and sophistication; their images sit alongside moody pictures of Hermès bags, vintage Porsches, Braun clocks, and Jean Prouvé chairs for inspiration boards. There is an abundance of media accounts also dedicated to Carolyn’s fashion looks, like @cbkalifeinfashion. Stellene Volandes, editor-in-chief of Town & Country, noted, “There are no real interviews, no photo shoots, no reality TV shows, and yet she is still on Instagram at least once a day, every day.”

In fashion today, Carolyn has touched most minimalist brands that oscillate with discretion, discernment, and luxury: Alaïa, Jil Sander, Khaite, Phoebe Philo’s Céline, The Row, and Bottega Veneta. They all extol Carolyn’s fashion tendencies and follow her blueprint to the detail. Her friend Tony Melillo aptly observes, “What is fascinating is you could see her style walking down the street today, and it would work. I think that’s pretty special, isn’t it? She didn’t have the impact she did because she was a Kennedy. She did it on her own.”

Close friends have confirmed that Carolyn’s wardrobe and jewelry box was relatively small compared to typical Manhattan socialite standards. Thrift and vintage stores were always a factor in her fashion Rolodex, places where she could find that certain treasure for herself or for a loved one. I often heard that she was an attentive and generous gift giver, always mindful of the recipient, leaving an inscription, as Lee had advised that “there is no point giving something without a message on it.” Her generosity had no bounds with family, friends, colleagues, and even staff: Claudette Marasigan recalls, “On helping her shop, she ended up buying ME these cool khaki skorts, which she insisted suited me when I tried them on. She bought me one or two other things if I remember, it was very touching. I received cards and flowers from her, she had such generosity of spirit.” Carolyn loved shopping for John, also; a few friends remembered an avocado-green velvet suit, picked by her.

Mid-century furniture was a favorite of hers, 20 years before it became commonplace. It was for a certain collector and taste. Carolyn’s refined eye found her center even with interiors. She borrowed clothes from other designers and would gift pieces randomly. Marrying into wealth didn’t mean she feasted on her mother-in-law’s jewels or chose to invest in her own collection. In fact, she kept to her relatively strict diet for formalwear, wearing one jewelry piece per outfit.

Mr. Blahnik had commented on this almost austere disposition Carolyn maintained while shopping; she was often granted all access to his store, but she took only what she absolutely needed and would always try to pay; she was never “greedy or demanding” and had the true markings of a lady. As a friend explained, she was not a compulsive shopper nor was she a “clothes horse.” She would often buy the same thing but in different colors, from shoes to individual pieces, exacting and almost frugal with her purchases. For sustainable advocates today, she has set an example for how our shopping habits could be. Our social and environmental responsibilities can’t be ignored, and now as “overconsumers,” we must face them. I have a feeling that if Carolyn were to acknowledge or feel comfortable with the concept of a legacy or a book in her name, it would be to support a cause like this.

Excerpt from the new book CBK: CAROLYN BESSETTE KENNEDY: A LIFE IN FASHION, by Sunita Kumar Nair, published by Abrams.

Text Copyright: © 2023 H11, Inc.

Page 24 credit: © Globe Photos/ZUMA Wire

Page 43 credit: © William Regan/ZUMA Press

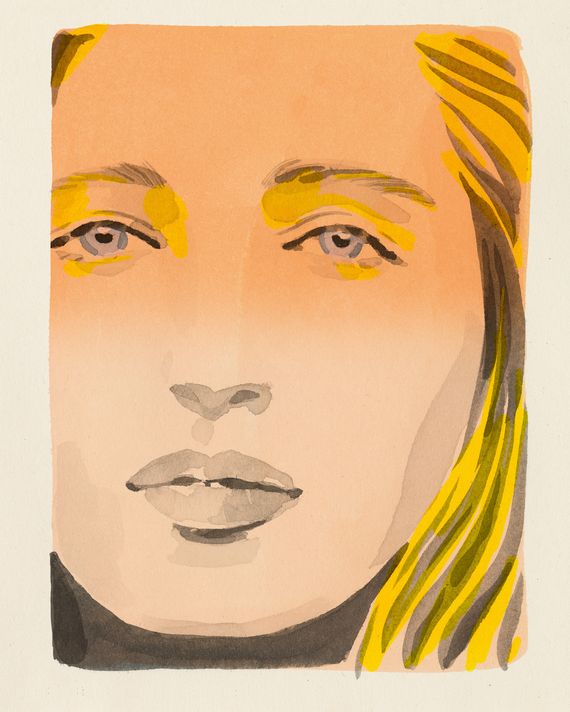

Page 172 credit: © Cecilia Carlstedt; Page 172 caption: CBK, by Cecilia Carlstedt, 2023.

Page 175 credit: © Robert Curran Photography; Page 175 caption: CBK and Betsy Reisinger Siegel, Miami, 1998.