Warning: NSFW spoilers for Challengers ahead.

The most sexually charged scene in Challengers is not the one you think. It happens about halfway into the movie and less than a year into the ever-shifting relationship between tennis players Patrick Zweig (Josh O’Connor), Art Donaldson (Mike Faist), and Tashi Duncan (Zendaya). Tashi is dating Patrick — much to Art’s barely masked chagrin — and the guys pop over to a courtside snack kiosk for a spontaneous check-in about the not-so-happy couple. I wish I could tell you exactly what they talk about, but I spent the entire scene fixated on two churros bobbing in and out of the frame. These semi-rigid cinnamon-sugar phalluses are hard to ignore for a number of reasons: Patrick is not the kind of guy who waits until he’s done chewing to tease his best friend, so most of his jabs are garbled through a thicket of deep-fried dough; his face is also covered in churro dust, which Art tenderly reaches over to brush off halfway through their conversation. By the time the boys are snatching cheeky bites of each other’s pastries, their conversation is irrelevant.

Luca Guadagnino’s Challengers, or, as it’s more widely known, “the Zendaya tennis-threesome movie,” is filled with scenes like this one, in which the homoeroticism is palpably, almost comically in your face with innuendos and eyebrow wiggles without explicitly making its way into the dialogue. There’s a ton of playful guy-on-guy wrestling (totally platonic, they swear!), some calculated eye contact while Patrick bites into a banana, and a buck-naked sauna standoff. Although Patrick and Art spend most of the movie chasing Tashi’s affections, they have far more sexual tension between each other — making this love triangle, to put it crudely, gay as hell.

The queer chaos of this particular dynamic is not unique to Challengers. Around the same time that polyamory moved firmly into the territory of Brooklyn brownstoners, I started to notice triads involving one woman and two men popping up in all kinds of places — Gucci perfume ads, Marvel comics, the Ira Sachs movie in everyone’s group chats. While such love triangles might once have been the stuff of esoteric art films and independent European cinema, they’re now making a big entrée into mainstream culture — and into one of the splashiest movies of the spring.

The three-way setup that makes Challengers feel so culturally resonant can loosely be defined as MFM: a threesome in which the two male participants don’t interact with each other sexually. (You may also know it by its more frat-bro-friendly name, the “Devil’s three-way.”) The movie flirts heavily — like, really heavily — with the prospect of an MMF threesome, which would involve overt guy-on-guy action, but stops just short of letting it play out. That’s to its advantage — if Art and Patrick had already had sex by the time they were crossing churros, that scene wouldn’t be nearly as thick (sorry) with sexual tension. Instead, their relationship is one long, torturous tease. Even the film’s much-discussed hotel-room scene shows Tashi manipulating her “little white boys” into a hot and heavy makeout sesh, but she calls it off before anything goes further — leading not to a mid-tournament ménage à trois but to Patrick slapping Art’s boner on his way out of the room with the nonchalance of a doubles player giving his partner a high five after a well-placed lob. Tashi may have promised her phone number to whoever wins their match, but this competition is more than a little friendly.

Art and Patrick’s dynamic is proof that our culture seems to find something fascinating about men who suggest they might go both ways. Even the mere sight of Tashi drives Patrick to confide in his best bud, “I’d let her fuck me with a racket.” Though the movie is certainly interested in our largely internet-driven fixation on bisexual men — later, we find out that Patrick, at least as far as his dating-app settings go, is into men and women — that’s not the only thing that makes its trio so alluring. After decades of popular movies casting female bisexuality under a male gaze (Vicky Cristina Barcelona, Wild Things) while playing guy-on-guy action for laughs, switching up the arrangement feels like progress on two fronts: Queerness is actually taken seriously, and you’re far less likely to end up with scenes that objectify women in the throes of pleasure. In fact, Challengers descends from an older, more niche era of stories that use the MFM dynamic to put women in full control of their sexual encounters, parlaying two straight male love interests into something much racier, murkier, and far more queer.

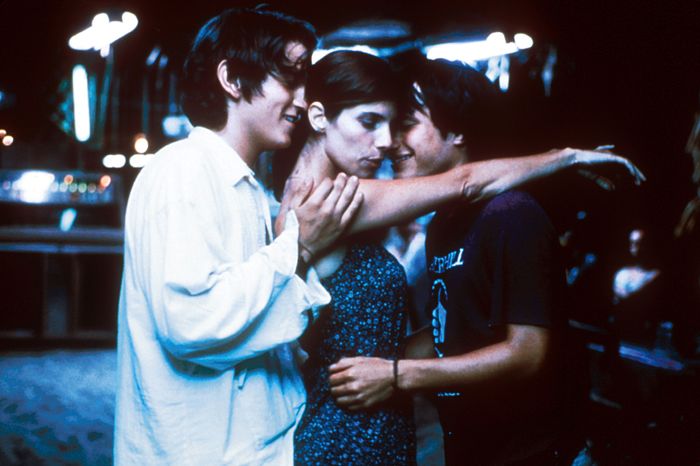

In the late ’80s and ’90s, queer cinema pioneers like Gregg Araki often used erotic dalliances involving two men and one woman to challenge the monogamous love triangles of mainstream entertainment. In his 1995 film The Doom Generation, Araki put a trio of hot young outlaws — a straight couple of rebellious teens and their mysterious criminal interloper, Xavier — on a murderous road trip through an apocalyptic-looking California, culminating in a threesome. Doom’s opening title card cheekily bills it as “a heterosexual movie by Gregg Araki,” a nod to a producer who had told him his movies were too out-there for gay audiences and he could get more funding if he focused on a straight story line. When the film was restored and rereleased last year, Araki called it a “Trojan horse” — it may seem like you’re watching two men go for the same woman, but the chemistry between the guys is impossible to ignore. “The subtext of it is so ridiculously gay, it’s almost camp,” he said. Sound familiar?

Araki’s gonzo MFM antics have since earned their own cult following, but the bisexual threesome that found the most mainstream success is in another road movie: Y tu mamá también. Alfonso Cuarón’s sultry 2001 romance follows teenage best friends Julio and Tenoch on a spontaneous road trip with Luisa, the older wife of Tenoch’s cousin. It’s easy to see Julio and Tenoch serving as the blueprint for Challengers’ boyish doubles partners, whose homoerotic friendship is bound up in youthful athleticism and unrestrained teenage horniness. An early scene in which Julio and Tenoch trade commentary on each other’s dicks at the spa showers in a private pool club — after masturbating on parallel diving blocks — was almost certainly on Guadagnino’s vision board. Y tu mamá también uses the guys’ youth and inexperience to put Luisa in the driver’s seat (figuratively, at least; she spends most of the movie riding shotgun): She’s the one who initiates sex with each of the boys, she decides when it stops, and she directs, almost move-by-move, the eventual threesome.

But for all its box-office achievements, Y tu mamá también presents us with a relationship that still feels taboo. Taking place throughout Mexico in 1999, a time when the country was on the precipice of upheaval, the film puts its characters in transition — from one place to another, from one political regime to the next, from youth into adulthood. Where better to liberate three horny people from the constraints of mainstream sexuality than on the open road, in a liminal space where the rules need not apply?

If anything, MFM movies got even more transgressive with time. Two years after Y tu mamá también, Bernardo Bertolucci released The Dreamers, which follows an American exchange student, Michael, who has an erotic fling with French twins Théo and Isabelle — all while Paris explodes with the student protests of May 1968. The Dreamers — which just so happens to be getting a rerelease this year — found the idea of two men with a woman so perverse that it had no problem adding incest to the mix. The movie was as illicit as they come, and our memories of it are similarly racy — any 30-something cinephile will tell you they blushingly rented The Dreamers in secret or watched it with their finger hovering over the “Last” remote button.

Doom Generation too was stuffed with “666” references and anti-authority wisecracks that telegraph how this is a movie by, about, and for outsiders. Araki, whose early work is often marked by his signature scrappy, bare-bones production values and a rebellious punk-rock aesthetic, doubled down on that perspective last year when he said, “My movies are for the outsiders and the weirdos and the punks and the queers.” That’s the sensibility that has allowed erotic MFM (or MMF) triangles to thrive on the fringes of mainstream entertainment, where deviance is all but guaranteed.

Challengers is less for the punks than it is for the country-club members, at least on the surface. Instead of freeing its trio from the judgment of polite society, it embeds their deliciously messy dynamic in a sport that values rules, cleanliness, quiet, and emotional repression above all. Monogamy is all but built into tennis gameplay — in the most publicized matches, only two people can face off against each other at a time — and Tashi, Art, and Patrick rotate tortuously through all their pairings, never seeming satisfied with just one partner.

This movie is one big edgefest for its audience, too, but the tease is the point. After years of pop culture nestling queerness into palatable domesticity, Challengers wants to provoke, and it can’t do that if its characters are down to commit to life as a tennis power throuple. Like the transgressive MFM filmmakers before him, Guadagnino chafes against the limits of queer acceptance, less concerned with the mantle of representation than with reveling in the tension between what these characters want and what they have deemed acceptable.

What do Guadagnino’s predecessors think of this new generation of MFM storytelling? I called up Araki, who hadn’t seen the movie yet, to ask. “I’ve had people tell me, ‘Doom Generation made me fucking gay,’” he told me. “Challengers has a good chance of being that movie.” Plus, it’s a boon for onscreen churro representation.