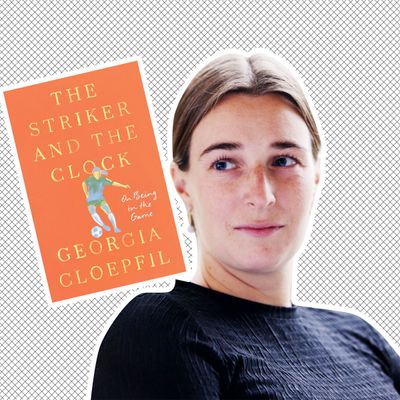

When Georgia Cloepfil began writing what would become The Striker and the Clock, she started by jotting down thoughts between practices. Cloepfil, who had been playing soccer seriously since she was a child, made a career as a professional forward, or striker, outside of the U.S., signing contracts in six countries — including South Korea, Lithuania, and Norway — over six years. When she was overseas, she published her first essay with N+1. “I was in Korea, and I remember the very room I was sitting in when I was emailing with my editor,” she says. “Being in dialogue with someone who understood what I was trying to say about these bigger ideas around soccer — I remember thinking, I would love to keep doing this.”

The book she eventually wrote is a lyrical account of ambition, frustration, and the occasional euphoria of playing. She’s attentive to the game’s small joys, but she also spends many pages on the reality of injury: throbbing toenails, nerve damage, the pain-killing injections that leave behind an uneasy numbness. Then there are the nonphysical strains. At one point, she writes out exactly how much each team paid her to play: $500 a month in Sweden; $1,200 a month in Lithuania; $37,000 a year in Korea.

Now, Cloepfil is a writing professor and assistant soccer coach at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington, where she lives with her husband. When we talked over Zoom recently, she leaned forward enthusiastically at the mention of the Olympics. “Getting Emma Hayes into the United States national team is so exciting — she’s a celebrity in her own right on this very celebrity team,” she says, then rattles off most of the rest of the roster. “The team is just a joy to watch.”

You write about how when you were a young soccer player, it was kind of a hard truth that there wasn’t a professional league in the U.S.; the Women’s United Soccer Association shut down after running from 2001 to 2003, and a successor hadn’t come along yet. Can you talk a little about what it was like to want to play this game but not know if you’d be able to do it long-term?

The league not existing, or kind of coming and going, when I was in high school and college meant I had to ask myself, “What are you aspiring to?” I grew up near the University of Portland, which was home to legends — Christine Sinclair, Megan Rapinoe, these women were playing there, and I went to every game with my little team. So first I aspired to play in college like the University of Portland girls, because that was something I could see.

I knew that I could go and play professional soccer overseas. But how do you navigate that? There’s very little information, so you’re Googling, like, “Who’s an agent?” and asking everyone you know and casting an enormous net trying to get a little bit of traction. Piecing together the agent, finding the right league, knowing anything at all about where you’re going before you go, those things were challenging.

There’s a scene in The Striker and the Clock when you’re looking at a Google Earth satellite image of a place trying to figure out what it would be like to live there. You’re stepping into the unknown, and you’re more or less at the mercy of the league you end up in, the coaches, the place.

That desperation sets you up for some vulnerability for sure. When you’re like, Any agent, anything, I’ll just grab on to that because I want to keep playing so badly. So when an opportunity comes in … Oh, I’m so grateful. I’m gonna cling to that with everything I have and just go no matter what, even if I’m a little skeptical and not making enough money or this contract looks a little weird or not what I expected. It’s so easy to look the other way when it’s the only opportunity that’s come up.

The book has a unique structure. It has 90 short passages meant to mimic the minutes in a game of soccer. Can you tell me a little about how you landed on that?

I didn’t want to tell the classic story about sports: “I was young, and I did this, and then I had an injury, I struggled, and then I won the championship.” I felt like if I followed my journey chronologically, I would slip into that narrative, but I still wanted to structure it in a way that sort of followed the arc of a career. There are 90 minutes in a game, so there are 90 small sections, plus one stoppage-time section, in the book. That artificial constraint itself also mimics the feeling of playing. You have to stop at some point, maybe when you’re very young in your life — I was really processing what playing meant to me right after making the decision to retire. The game ends, the season ends, and there’s this feeling of “When is it going to end?” that I wanted to have in the book.

The clock is ticking toward a final moment, even if the feeling of saying good-bye to the game is an unending thing. That’s how it felt while playing: It will end no matter whether you choose or not. It has to end.

You describe not really wanting to write about soccer when you were getting your M.F.A. How did you come around to making this the subject for your first book?

I think I had a lot of insecurities about what it meant to be someone who loves sports while also being someone who loves books. I just didn’t see a lot of that happening. On my soccer team, I was the nerd who read on our road trips. Then on the other side, in literary circles, people say, like, “No, I hate sports. I hate jocks.”

In writing this, I was trying to understand that there’s actually a lot of overlap. I wouldn’t be who I am as a writer without soccer. And I probably wouldn’t have been the same player and have the same career if I wasn’t processing things in the way I do as a writer. I’m interested in these really big themes that soccer brings up, like gender and ambition and endurance, which to me go so far beyond sports. And in grad school, I was still very insecure; I did not want to be The Soccer Writer. In the end, I was slowly accumulating this project on the side, and I finally had to admit that it was something that I really wanted to finish.

You talk about the realities of getting injured and feeling like you need to push through — it’s a very gendered thing in a way. At one point you write about endurance running, for instance, and how women can excel at that specifically.

There’s one side of it — I write a little bit about the science of why women start to surpass men at races that are 200 miles long. Is it because we’re built for that sort of thing, that women’s bodies are built to endure pain? Or is it because the world has demanded that we endure through pain to prove that we’re able to run a marathon, that we’re able to play soccer, to be on the football team with the boys? I played football, and I remember thinking, I cannot fall over or cry, because it’s all boys. And they already think I’m not tough; they already think I’m small and weak. I think maybe there is something physiological that enables women to succeed on these outer edges of endurance sports and also push through pain, to not flop in soccer, and it also becomes something that’s integral to the female athletic experience because it has been demanded of us if we want to prove that we want to compete on this stage.

In your memoir, you have this canvas of the soccer field, and you look at it in a really interesting, literary way. You write about how people anthropomorphize the ball — the personality of a soccer ball, the way it “crawls,” “tempts,” “has a mind of its own.” You also write about your teammates, but to me, the book felt very solitary.

That is definitely a tone in the book that I wanted to come through. I think there were two prongs to that loneliness. One was me traveling abroad, not knowing the language, not knowing people, and having soccer as a grounding force — the ball doesn’t change. The teammates were there for sure. But the professional locker room is a little different when international players come and go. It’s not the cohesion that you have on a rec-soccer team when you’re little and playing with your friends. Then I talk about the loneliness of playing, for instance, in Korea, where I was playing in stadiums built for 50,000 fans, and there were probably 100 people scattered in the stands. That feeling of more existential loneliness: Why am I playing when no one is watching? And what are we doing here? And what is the point if no one will ever see the product of our play?

Some of the best sports books I’ve read are about more obviously lonely sports: swimming, boxing, tennis. Each individual is in their corner. But there’s a different sort of loneliness and probably a more complicated loneliness in a team sport.

Even when the stadiums were quiet, though, competitiveness kept driving you forward in your career. But you also write about this pure experience of playing soccer that, on a physical level, is very joyful. How do those two things relate?

In writing this book, I started to understand that it’s harder to write about joy than it is to write about pain and suffering. Part of that is because the joy is all physical — you almost black out from adrenaline when you score a goal. All you experience is physical euphoria, which makes it really hard to translate.

There’s a hunger that is innate in someone who’s really competitive or really in love with something, whether it’s a sport or something like writing. It’s about trying to make public something that you really love, that maybe could be a hobby or something close to your heart, but you’re actually trying to achieve something very public. That sort of chasing is integral to the personality of someone who’s going to continue to play for a long time, or continue to write for a long time, or continue to make art, or to ride horses, or whatever it is. That compulsion toward movement is really integral to my experience.

More From This Series

- The Track Star Making Space for Moms in Sports

- Caitlin Clark Shuts Down Angel Reese Rivalry Rumors

- A Primer on the WAGs of the 2024 World Series