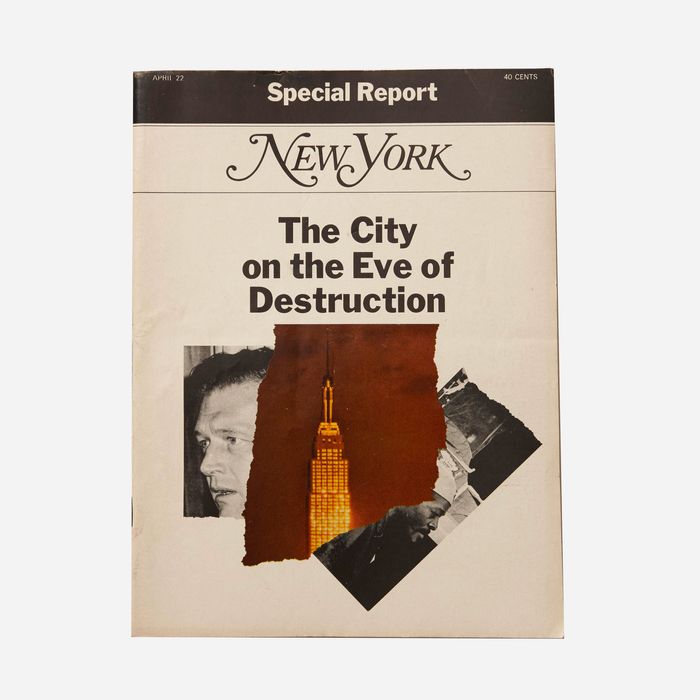

Editor’s Note: This story first appeared in the April 22, 1968, issue of New York. We are republishing a selection of Gloria Steinem’s writing from our archive to celebrate her 90th birthday.

It was a 7:15 curtain for opening night, so Mayor John Lindsay missed the first bulletin on the shooting of Martin Luther King. At 8:30 in the Alvin Theater, during a musical number called “Spring in the City,” a Negro detective got the second bulletin and started moving down the aisle.

It wasn’t the first time that Ernest Latty, a plainclothesman who serves as both aide and bodyguard, had summoned the Mayor to an emergency in the midst of theaters or public speech or the soundness of sleep. Probably, it would not be the last. But there was a special urgency in his face as he leaned past Walter and Jean Kerr, who were seated on the aisle, to hand the Mayor a note and beckon him outside. Lindsay turned to his wife who signaled to go ahead, she would stay. A good idea, he thought as he brushed past, excusing himself to the Kerrs; this was an important opening night for actor Tom Bosley, an old friend, and it wouldn’t do to have both of them leave.

But all thoughts of friends and musicals and opening nights left him as he read the fact of King’s assassination, and understood the enormity of it, and began to sense the loss. He thought: It’s stunning, it can’t be true; like Kennedy. He thought: A wild reaction, all over the country. He thought: And here.

His car was waiting outside, the motor running, but Lindsay dashed first to a telephone booth. Still in the glow of a marquee announcing The Education of H*y*m*a*n K*a*p*l*a*n, at which he had been laughing seconds ago in another life, he checked two key information centers — City Hall press headquarters run by Harry O’Donnell, and the police communications office.

But for now, the only answerable questions were small ones. In the car speeding toward Gracie Mansion with Detective Latty and communications consultant Dave Garth, Lindsay began to plan his next few hours.

He wanted to go to Harlem, that much was sure. Some kinds of riots — over rats, garbage collection, welfare complaints, for instance — usually start in younger, more volatile ghettos like Brownsville or Bedford-Stuyvesant, spreading to Harlem only by contagion. But this one, the Mayor knew, would be born in central Harlem, the country’s oldest, most politically sensitive concentration of Negro leadership, if it were to happen at all. “Besides,” he said grimly, “somebody just has to go up there. Somebody white just has to face that emotion and say that we’re sorry.”

But wouldn’t a white face, even one as accepted in the past as the Mayor’s, be an incitement to revenge? The police routinely resist Lindsay’s fondness for walking tours, but there was a real need for caution tonight. How fast could Urban Task Force members be put to work, and how many of their contacts would hold?

Lindsay decided to telephone neighborhood leaders, and to check police and fire alarms again, before heading uptown. He was quiet for a moment; then referred briefly to the President’s Riot Commission Report. He had worked on it for six months. It was generally known that he had a lot to do with writing the controversial summary, and he had been criticized severely for that. “We’ve got to admit we’re in danger of breaking into two countries, black and white,” he said. “They called the Commission Report too strong. But look what’s happened.”

At Gracie Mansion he went directly to the office and conference room in the recently built Susan Wagner wing — more than City Hall, the Mayor’s inner sanctum workplace — and asked four secretaries to arrange shifts for manning the phones. There would have to be a full-time command center tonight.

No reports of incidents had come out of Harlem yet, but street loudspeakers had just begun blaring the news. Policemen and fire trucks were being sent uptown in force, and to ghetto areas in Brooklyn. The Urban Task Force — a group of about 40 officials from all city departments responsible for street welfare, plus 18 neighborhood heads who do this in addition to their various city jobs — had already been activated by its chairman, Barry Gottehrer, and was relaying work from its multiple neighborhood contacts that things looked “really uptight; bad.” But, equally important, the Task Force was functioning, even that part of it that contained white faces. “If your contacts were good before, they’ll be good now, one black leader said to Gottehrer, “even if you’re white or Puerto Rican.”

So, at 10:30 p.m., Lindsay got into an unmarked black Plymouth with three of his aides, and drove uptown. He would get out and walk or not, depending on what he found, but he wanted to be there.

It was a quiet ride, with the sweet spring air making the silence of the streets more ominous. At the 25th police precinct in central Harlem, Lindsay got an intelligence report that the area was “heating up”; then left the car with a very worried Dave Garth behind the wheel at Eighth

Avenue and 125th Street where people were gathering, and began talking to them in twos and threes, steadily moving toward Seventh Avenue so that a big crowd wouldn’t form, expressing his sympathy to individuals.

Women stood with tears streaming down their faces. Groups gathered silently outside record shops where loudspeakers blared news of violence in other cities, or the speeches of Martin Luther King. Both were frequently drowned out by sirens — a fire had started a few blocks away — or by the staccato of police calls from a nearby squad car. Small packs of teenagers were hanging back, laughing uncertainly, waiting.

With Latty, another plainclothesman, and Barry Gottehrer following behind, Lindsay was received distractedly, but with warmth. Men gathered around to stand wordless, or to greet him, or to shake his hand. “That’s the Mayor,” said a tough-looking kid, impressed. Two of the weeping women complained about the police barricades on 125th. “This is our street,” said one bitterly, “and we can’t even get through.” Lindsay was also doubtful about the blocking-off technique. It might form people into stagnant, dangerous groups; and it was causing resentment. “Better keep them moving, don’t you think officer?” he said, drawing a policeman aside for “a chat.” The set of barricades was removed.

More sirens. More clanging of fire trucks. “Man,” said a big kid in an athletic jacket happily, “there’s gonna be white blood in the streets tonight.”

On the third floor of a building across from Frank’s Restaurant, on West 125th Street, a favorite of Harlem’s elite, the Mayor met for 40 minutes with Joe Overton, a labor union leader, and other Harlem representatives. As part of a strategy to defuse 125th Street, the Mayor was to walk north, drawing some of the crowd to 126th.

Police Commissioner Leary arrived, took one look at his deployment of forces from the window, and went down to get the barricades and cross-parked police cars out of there. Better to keep the traffic moving, he decided. From the Byzantine possibilities of police tactics, he had to choose carefully. One arrest badly handled, one shot, and the whole place could be uncontrollable.

More people had gathered when Lindsay came down to act as Pied Piper. Bobby, one of several Harlem operators Lindsay had got to know in the streets, swung his six-five, 260-pound hulk in step with the Mayor. “Don’t worry,” he said grinning, “nobody can get to you while Bobby’s here.” Harlem leaders from the meeting had already assigned a couple of extra bodyguards, and Barry Gottehrer was worried. He didn’t like Lindsay walking with that kind of group around him; it attracted trouble. From the car, Dave Garth watched critically, too. The decoy to 126th Street was working, but the crowd was getting too big.

At the CCNY campus uptown, several hundred students were watching a concert of African- American dance and music, when somebody ran into the auditorium and announced that Dr. King was dead.

Leaving the auditorium in the middle of the concert, almost 200 students, black and white joining hands, began marching down Convent Avenue to 125th Street, until they ran into Lindsay, who asked them to disband.

“We stopped,” said one student in the march, “but other people had followed us, you know, and then they started this.” The “this” was sporadic looting, rock throwing, and starting some of the 50 fires that were reported that night. Two men, their arms bulging with loot from a nearby men’s store, rushed out, unseen by members of the tactical police force who stood four abreast across the street from the Baby Grand Night Club. The CCNY student, a young woman, was shocked and confused, as the march had moved into a world lighted by the revolving lights of the police vehicles, rising smoke, and screaming fire engines. “He didn’t approve of violence,” she mumbled, “and it ain’t right to do this.”

Like many of the student marchers, they were children of the Black Power Revolution. Martin Luther King had not been their hero. Their heroes were Stokely Carmichael, Malcolm X, and LeRoi Jones. In their student world of Camus, of Fanon, and Malraux, Martin Luther King seemed antithetical to all that world symbolized. But in spite of their present militancy, the dream of Martin Luther King was more than the dream of their fathers.

“That’s it for me, a neatly dressed young man said. “They do something like that to man like King … a man like King.”

For the leaders, the activist heroes, the dilemma was even worse. Privately, most of them — even Rap Brown — had admitted that they hoped in their hearts King was right.

“Now,” explained black militant Addison Gayle, “we’re all a little scared. Because we have to believe our own rhetoric.”

Lindsay kept going. To one side, he noticed Allah, militant leader of a black youth group called the Five Percenters, signaling his followers north to help the defusing plan. This was a result, the Mayor knew, of Allah’s contact with the Task Force, but parts of the press still equated any militant with “hate whitey.” Later, store looters were identified on television as Five Percenters.

Allah and some Five Percenters were in the crowd close to Lindsay, and rivalry was developing over who was to shepherd the Mayor. There was a little jostling and complaining. Gottehrer was pushed aside roughly, but Lindsay seemed in no more than normal danger. Bobby got separated, and gave Allah a brutal shove on his way back. The Five Percenters — who believe their leader is really Allah, the god: many had no permanent person in their lives until he took them off the streets — threatened to beat up Bobby for this insult. He replied by calling Allah something not quite audible, but obviously foul. Others in the crowd had to keep the Five Percenters from tearing Bobby apart.

The disturbance wasn’t directed at Lindsay, nor was he involved, but he was too far away from Dave Garth and the car. Borough President Percy Sutton had his limousine nearby, and urged Lindsay to use it. Bobby wisely jumped in too, with the bodyguards, and the walking tour was over.

As they headed back toward Gracie Mansion — through streets emptied by terrified whites, past barricaded doors of apartment houses, past rooms in which men brought out old hunting rifles, certain that black guerrilla-fighters would come — Bobby was cheerful, except for one thing: somebody had managed to steal his watch. Right off his wrist! Lindsay laughed for the first time that night. Anybody who could lift a watch off Bobby, who had probably acquired a few in his life; anybody who could do that was something.

It was 11:30.

Mary Lindsay came home from the theater expecting to find chaos, but two of her daughters were playing a card game called Pig with staff members on the floor of the office, and everything seemed under control. She set about getting coffee for what she knew might be an all-night siege.

The Mayor arrived to be given reports of more fires and the start of looting, but nothing like the severity of the situation in Washington or Chicago or even Nashville. Television news showed policemen and National Guardsmen in other cities, horrific in their gas masks and bayoneted-rifle gear. In New York trouble spots, about 5,000 police and firemen were being deployed, but with no equipment more unusual than an occasional riot helmet. So far, none had responded to taunting and bottle-throwing. Arrests had been made carefully and without incident.

At 1 a.m., having checked all information centers, the Mayor again drove uptown. He didn’t get out — his aides had dissuaded him from that — and his own Plymouth was preceded by a blacked-out squad car, but he spent an hour crisscrossing from river to river, surveying the damage and trying to assess the mood.

Refuse and broken glass littered the main streets, but many of the crowds of two hours ago had dispersed. There was no real riot. Yet.

At Gracie Mansion, Lindsay ordered an extra force of sanitation men to be out with hand brooms by 6 a.m., removing all traces of last night’s violence. He had learned from two hot summers that slum-dwellers who wake up to neatness and order are much more likely to keep it that way. (The usual riot consequence is refusal of sanitation men and other city employees to enter the area. In Newark, rioters were goaded on by garbage in the streets as well as tanks.) The psychology of despair is a delicate thing.

More phone calls, more talks with the staff, more trying to get the mood of the ghetto. Finally, too tired to look at the clock, Lindsay fell into bed. It was 3 a.m.

Every Friday morning at eight in the Blue Room of City Hall, the Mayor holds a Cabinet meeting of all department heads. Sitting around on folding chairs, sweating, arguing, losing their temper and sometimes their jobs, about 40 men try, with widely varying intelligence, to figure out what’s happened in the past week and follow some rational direction in the next.

This session began with a moment of silent prayer for Martin Luther King. Deputy Mayor Timothy Costello was chairing because the Mayor had left Gracie Mansion at 7:30 a.m. to survey Harlem by daylight. When he finally arrived in the Blue Room at 9:05, he had seen the smoking ruins of a fire that started after he went to bed, checked police intelligence, and noted with satisfaction that we were in for a cold snap that might help cool off the streets.

The next meeting: With the Fire and Police Chief, and aides Lee Rankin, Sid Davidoff and Barry Gottehrer, Lindsay discussed upper-level workings of the Urban Task Force.

And the next: A press conference at 11:30, one of two he routinely holds each week. Only this time, there were non-routine questions.

And the next: An emergency gathering of the 18 neighborhood Task Force leaders (each one being responsible for a unified area, like Williamsburg or Brownsville), plus ten more community leaders and city employees drafted for the duration. The main topic was the emergency communications system. In normal times, the whole Task Force meets once a month, with neighborhood leaders sometimes upping that to once a week. Now, meetings were to be held every day, with special telephone lines set up for hourly contact.

About 2:30, Lindsay had a brief respite. That is, he got back to the street.

Touring the section he refers to casually as “Bed Stuy,” the Mayor missed a ragged but irate march on City Hall. It had grown out of a memorial demonstration in Central Park attended mostly by students and addressed by Dr. Spock. (“Dr. Spock and all those people are very nice,” said a glum Dave Garth when he heard about it, “but what happens to the crowd after they leave?”) One of the speakers, an officer of the Du Bois Clubs, accused Lindsay of wanting to use tanks against people in Harlem, and called for the march down Broadway. Most of the marchers weren’t that angry. The only damage was broken windows at a bar and the Recruiting Station in Times Square.

At 3:30, Lindsay was back in Harlem for the fourth time in 18 hours, making a stop at the Glamour Inn to thank Allah and his militant Five Percenters for their peace-keeping help. Until last year, the police had considered Allah’s group of 800 or so followers to be a violent and anti-white group. Then Barry Gottehrer discovered that what Allah really wanted was some education for his young disciples, and an occasional bus trip to the country. (When Gottehrer, surprised at this small demand, actually arranged for a chartered bus for a day’s outing, Allah said it was the first time any white man he knew had kept his word.) Lindsay stood in their favorite hang-out, thanked them warmly, and everyone looked very proud.

Walking east along a busy but peaceful 125th Street, smiling and shaking the dozens of hands stretched out to him, Lindsay bore little resemblance to the man who, according to the press, had been forced out of Harlem last night by hostile, bottle-throwing crowds who wouldn’t let him speak. The New York Times gave the impression that the animosity between Allah and his followers and Bobby had been directed at the Mayor; possibly because they didn’t know who Bobby and Allah were. (Besides getting them a bus, Barry Gottehrer gained the confidence of Five-Percenters last year by getting the Times to change a story referring to them as “anti-white”; a misjudgement made by one reporter, and repeated by the journalistic custom of writing from clips.) Harry O’Donnell called a reporter who had written about “missiles” flying through the air around the Mayor last night. What were they? Pop bottles? Rocks? O’Donnell had been there, too, and seen none. “Just missiles,” said the reporter.

In combustible times, even small exaggerations are dangerous.

“Rumors,” notes the Riot Commission Report, “significantly aggravated tension and disorder in more than 65% of the disorders studies …” Some choice ones circulated that night in white Manhattan:

Negroes are going to dynamite all tunnels and bridges.

The New York Stock Market has been bombed. (Police investigated a bomb scare there, but found nothing.)

All public transport has been stopped.

A white girl and her mother were knifed to death on Madison Avenue for the mother’s mink

coat.

Negro veterans from Vietnam are planning sniping attacks to panic the city.

As a result of rumors, or generalized terror, midtown was strangely empty. Broadway theaters couldn’t sell tickets, and many restaurants were deserted. Some big companies closed early and small ones sent their women employees home. By 8 p.m., many taxi drivers had gone in, and the streets were deserted caverns. Couples canceled dinner parties, and ordered their children away from windows. Doormen worked in pairs for security. A woman in Sutton Place called the police for someone to walk her dog.

A doorman of a luxury apartment going to work on an almost deserted subway found himself facing a pistol in the hand of a black man wearing a black armband of mourning. Terrified, he pulled a crucifix from his pocket, held it up, and pleaded, “What do you want with me? Look. I’m a Catholic.” The gun was lowered. “Get off this train at the next stop or I blow your brains out,” he was told. He got off.

In black Manhattan, the rumors were more fearful. Those of the underdog always are:

They’re going to burn us out, block by block, and say we did it.

They’re using Mace. They’re putting something in the water.

A white gang is coming up with guns.

They’ve got concentration camps all ready for us in New Jersey.

Downtown, they’re happy that Dr. King is dead.

In the ghettos the suspicion and fear was like tinder. A few militants were already urging people to strike before they were struck. One police misjudgement, one anarchist, or one black-white street fight could set the match.

There were some private feuds adding to the tension in Harlem Friday night. The Five Percenters were still out to avenge Bobby’s insult to Allah. That night black extremists distributed a mimeographed sheet accusing Allah — mainly because of his peace-keeping activities of the night before — of atrocities like “cutting black women” and being in league with the whites. (The sheet also called for the murder of all black policemen.) There was another, older animosity. Allah, considering himself the real Allah, believed Elijah Muhammed should be his messenger, which the Black Muslim leader felt was sacrilege.

At 8:30 Friday night Jesse Gray, Harlem tenant leader, stood at the corner of 125th Street and Lenox, urging people to wait for the sound truck to arrive so the rally he had called could begin. Finally the truck arrived and the crowd grew silent and faced the platform. Toward the front a junkie kept his eyes fixed on a beautiful sister with a natural hairstyle.

Jesse began: “The white man got off the Mayflower shooting and killing Indians and now it is his objective to kill off the black people. Four years ago on July 19th, 1964, we served notice … it’s been four years now and there are more white cops now than in 1964.” The junkie staggered, and his eyes never left the girl.

The next speaker was Charles Kenyatta, sword-carrying commander of a paramilitary group called the Harlem Mau-Maus. Earlier that evening, stirred by the Mayor’s personalized tactics in Harlem, he had manned a sound truck to break up a gang of kids threatening trouble. Later, in a television interview, he said: “Lindsay helps because he’ll leave Gracie Mansion on five minutes notice, and he’ll talk to the bottom of the barrel.”

Now, Kenyatta addressed the crowd. He used the rhetoric of revolution — a militant leader has to stay ahead of his followers — but he was telling the crowd to cool it. “Let me tell you something,” he began. “When Mayor Lindsay comes up here, how come he’s always talking to those bullshit leaders in Frank’s. When he comes up here, we want him to talk to the people. Young people who don’t own nothing. But he don’t, so you know what you got to do. And don’t be snatching no drawers or shoes either — we must have a higher revolution than this. These n–– are crazy. If this city must be flattened, let’s do it downtown. And I’m telling all of these leaders to put up or shut up because a revolution don’t have no leaders. This country is up for grabs. We gonna move this thing until King’s dream turns into a nightmare.”

Livingston Wingate, a former director of HARYOU-ACT, was the next speaker. He spoke to an authentic emotion in the crowd. “Brothers and sisters of the colony of Harlem,” he began, “they have us in another crisis, but we are the children of crisis. Before the white man killed King, they killed his movement … King was simply waving the Constitution right back at them. And they snatched it, put it in their hip pockets and shot him down … and he wasn’t the first either. Remember, Carmichael, Rap, and every other militant used to be a part of King’s movement.”

His voice trailed off as the crowd took up the chant: “We want Whitey! We want Whitey!” The junkie straightened up, his eyes opened wider, and he went toward the girl, “wha’s your name girl? You beautiful bush-head, you look like wild African lady.”

“Them people out there are stupid. They’re just showing my Five Percenters they are blind, deaf, and what?”

“Dumb!” came the chanted answer.

“We are the only ones who are civilized. We are trying to save our people’s lives. The revolution

must come from within. Clean up your homes first. Our job is to civilize the what?”

“Uncivilized!”

He turned to one member, “If a Five Percenter don’t listen, the penalty is what?”

“Death!”

“There is no teaching in a bar. Bakar Kasim and two sisters got busted over in Brooklyn where they were teaching. Some cops come messing with them, and one of the sisters bit him on the hand. He shouldn’t have had his hand on her, and the man should have took his head! Now, you know we believe in peace, but I didn’t say if we are attacked don’t fight! You say you are God, and a sister is in jail for biting a policeman on the hand. Malcolm said he’d rather have the women than the n––. And another thing I taught you was to respect the American Flag. You respect any what?”

“Government!”

“I’m telling you, my Five Percenters have got to be healthy, strong and good what?”

“Breeders!”

“But you’re healthy all right. Some of you brothers outrun a reindeer or a telephone call every time a riot starts. You ain’t ready! You can’t fight no guerrilla warfare here, because you don’t plant nothing. You have to buy from the white man. Why? Because when his superiors give him the orders, the penalty for disobedience is what?”

“Death!”

“You’re out there looting. My wife had to go downtown to get some milk. Some brothers are looting. Don’t say you’re a Five Percenter if you gonna do it!

“You say you the civilized of the world. The white man won’t give you this government until you have given your word you will not destroy him.”

Whatever the black extremists were writing about him, Allah himself seemed monumentally unconcerned. A wiry, squinting man of 40, whose real name is Clarence “Puddin” Smith, he had lived through a break with the Black Muslims. (He once was a member.) Through a murder attempt that left a bullet lodged in his chest. (Allah was “on the list” after Malcolm X.) And through a stay in the Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, which probably got him out of a murder rap of his own. (He was allowed to plead insanity. After all, he thought he was Allah.) That bullet, plus an intricate mathematical catechism perfectly memorized by all his followers, proves that he is ‘Allah,’ the Islamic word for God. To those who doubt him, he says, “If I’m not Allah, who is?”

In his storefront academy at 127th Street and Seventh Avenue — financed by the Urban League, which is preparing several of his followers for college entrance — he conducted a Friday night teaching session.

“Peace!” about 80 of his followers shouted ritually as he entered. He stood in the middle of the floor and began a tirade, punctuated only by the words he left out, which the Five Percenters efficiently filled in.

Allah is one of many youth leaders, some in contact with the Urban Task Force and some not, who helped keep the peace Friday night, along with such groups as Harlem CORE, the NAACP and Haryou’s Neighborhood Boards. When the meeting was over, Five Percenters began filing out past a life-sized photograph of the Mayor and Allah. The inscription read, ’To Allah, thanks a lot, John V. Lindsay.’

Business was brisk in Harlem and Brooklyn all Saturday. The burnt-out stores, that were being cleaned out, and guarded by calm-looking policemen, could almost be ignored. Police had resisted pressures to make mass arrests for the looting last night. The concentration camp rumors had not been supported by one gas mask, or one bayonet. Harlem was returning to its normal condition of simple struggle for day to day survival.

Harlem is a community which, while it easily identifies a common enemy, is so torn internally and so divided against itself that it is usually helpless to help itself no matter what course it may choose. It has immense cleavages between its middle class and the man in the street, between its old and young.

The black middle class are called “boojies,” (from bourgeois) and the resentment of them can surpass that held for whites. Their numbers have increased in recent years as thousands of middle-income positions have been made available on the anti-poverty payrolls. These poverty profiteers are bitterly referred to as poverticians.

The bar at Frank’s was filling up with its usual Friday night clientele, who spoke only occasionally of King or the violence on the streets.

“Hell, they can’t burn down Lenox Terrace, one was heard to exclaim jovially.”

Another greeted a late arriving friend with, “Hey, baby, you up here to cool ‘em?”

“Sheeit,” came the reply.

“Yeah, I know. It’s got to be in the upper brackets for you. Ha Ha Ha!”

The crowd continued to gather. Labor leader Joe Overton; Judge Andrew Tyler; Assistant to the Borough President Mel Patrick; Amsterdam News editor Jesse Walker; author-playwright Loften Mitchell; City Commission on Human Rights Chairman William Booth; State NAACP President Donald Lee, and others.

Randy Rankin, the architect of HARYOU-ACT neighborhood boards stood chest to chest with Inspector Eldridge Waith, who was recently promoted to Assistant Chief Inspector of the police force.

“The people didn’t like Martin Luther King,” Inspector Waith analyzed, “but it was a releasing of emotions. The cops weren’t the targets like in Newark and Detroit where the triggering instruments involved cops. Of course,” he continued, “the people were tense and emotional last night, and probably will be tonight. I know I was crying. But people do need to get things off their chest and the cops know it.”

It wasn’t until 1 a.m. Saturday morning at Jock’s Place that the Mayor began to relax, to believe that things might be all right, “at least for another day.”

Barry Gottehrer had phoned Lindsay to come to this Harlem bar and restaurant, a hangout for local politicians, and witness an extraordinary event. Donald Washington, the one Negro on whom Gottehrer had focused his personal fear (Washington had once threatened convincingly to kill him) now wanted to work with Lindsay. And there were a lot of Democratic machine Negroes at Jock’s — men who had opposed Lindsay as a Republican if nothing else — who now seemed rather grateful to have him. Moreover, these were some of the men who, in the old system, had been called on by white politicians whenever black faces were needed in the ranks. (Harlemites refer to it as the “Hertz Rent-A-N–– Service.”) In a riot, few of them were much more help than their middle-class white neighbors in Westchester or Long Island, so Lindsay’s administration tried to eliminate the middleman and go right to neighborhood groups.

Lindsay arrived at Jock’s about 1 a.m., and was welcomed like a member of the club. He shook hands with former wildman Don Washington (who explained that he had changed; he had a wife and baby now), and stood at the bar with politicians who once campaigned against him.

At 7 a.m., John Lindsay Jr. tiptoed into his parents’ room with an urgent question about the location of some toy trucks. He had been moved in with his sister to free a bedroom for Lindsay’s aides who were working in the Mansion around the clock, and his 7-year-old sense of order was offended.

The Mayor, who got to bed at 3 a.m. after the usual round of phone calls, felt justified in putting a pillow over his head and pretending not to hear Mary’s whispered replies. Miraculously, there had been fewer fire and police alarms last night than on an average Friday.

But by 8:30, he was up, having breakfast, and making calls.

Since Thursday night, journalists and TV newsmen had been pressuring O’Donnell for advance notice of Lindsay’s walking tours. Partly for the Mayor’s own safety, and partly because cameras, lights and reporters were in themselves an incitement, the information had been refused.

But today seemed comparatively calm, and the press wanted badly to get pictures of Lindsay “making the magic.” (Were other mayors seeking Lindsay’s advice?, asked one journalist. “Sure,” said Dave Garth, “we’re glad to explain our system. But the first thing you need is a mayor who can show himself.”) O’Donnell agreed that he would make some brief release on the walks after they were over.

Brownsville: He walked for a while amid crowds of Saturday shoppers on Pitkin Avenue, and stopped at Smitty’s for a hot dog and coffee. A small group talked to him while he ate, their number changing as passersby stopped for a while and moved on. They talked about Martin Luther King, about their fear of riots, about looting. Some waved as they passed, and called out, “How you doin’?”

Bedford-Stuyvesant: At a Community Youth In Action storefront, at a looted store called Winston’s TV, and anywhere people stopped to talk, Lindsay conducted Instant Seminars along Fulton Street. “Why don’t you go back to Gracie Mansion!” shouted one man in one of the day’s few sour notes. At the corner of Bedford Avenue, Chuck Willis, a Task Force worker, was standing with the Mayor’s group, and so was Barry Gottehrer, but neither saw an elderly man get struck by a car until Lindsay dashed out to help. Apparently, all those walking tours have given him the eye of an Atlantic City lifeguard. An ambulance was sent for, and Lindsay stayed with the old man until it came.

Harlem: At WLIB, where he frequently takes on-the-air questions from listeners who telephone in, Lindsay spent 40 minutes doing an impromptu community radio show. Striding out onto Lenox Avenue with Willis, he immediately became a moving magnet.

“Man, he only some itty-bit shorter than Wilt the Stilt!”

“He ain’t never gonna get killed, because we like him.”

“Thank you, Mr. Lindsay. Bless you for coming up to see us.”

“God bless you, Mayor Lindsay, we love you.”

He got back in his car, smiling.

There was one more hurdle to get past, one more mass meeting that could be the lightning rod for violence: the Sunday memorial ceremony for Dr. King in Central Park.

Lindsay had tried diplomatically to discourage any plans for Sunday. But the fact that there had been no violence thus far was used as a pro-memorial argument by Rockefeller, whose idea the Sunday program was. It was necessary, apparently, for Dr. King to be paid a highly visible Establishment tribute in New York State.

For one bad moment when uptown groups got to the park, it seemed calmness was at an end. They found all the space around the bandshell occupied, mostly by midtown whites, and the merging wasn’t easy.

But when Lindsay arrived — taller than anyone in the crowd and movie star enough — there was a surprising round of applause.

The ceremonies ended in peace and surrealism. Rockefeller put his arm around the shoulders of

Allah, a Baptist minister thanked Kenyatta in a prayer, Percy Sutton referred to Mayor Lindsay as Mayor Wagner, and a Du Bois Club anti-Vietnam banner for Dr. King was held up for an

admiring white photographer from the News.

There had been no riot.

Mary Lindsay was watching television, looking at the smoking ruins in Washington. There had been troops ringing the White House and tear gas and crossfire; even tanks on New Hampshire Avenue. “It all seems so strange,” she said. “It’s a sight one can’t quite believe.”

In more than 40 American cities, there had been disturbances serious enough for some form of martial law, or weapons usually reserved for a battlefield. In New York, the biggest city, the place where everyone expected it to happen: There had been no riot.

The real reason was in the ghetto-dwellers themselves. Restraint in the face of despair came from unexpected people, unexpected groups. Other reasons were smaller, more tenuous, but just as important: sweeping the streets; chartering a bus; arranging a reconciliation between Bobby and Allah (as is now being done); setting up an all-night phone system; having the Task Force ready to go; and electing a mayor who can show himself. “If Lindsay hadn’t gone up there,” said one black militant, “if he hadn’t known who to talk to, we might have felt a lot different.”

New York will need a lot of luck if all these variables are to hold together again.

“The patience of an oppressed people cannot endure forever.” —Martin Luther King.