Editor’s note: This story first appeared in the January 26, 1970, issue of New York. We are republishing a selection of Gloria Steinem’s writing from our archive to celebrate her 90th birthday.

I am opening my mail one snowy morning, and, sandwiched in between the seventh computerized bill from a New York store where I’ve never bought anything and a fan letter suggesting I kiss the flag (due to “obviously pro-Communist” column on Agnew), I find a cheerful notice from Congressman Ed Koch.

“During the New Year recess,” says the printed letter, “I will be in New York City and would like to meet with constituents to hear your problems and ideas as well as to share some of my own views …” There follows a list of neighborhood subway stops where the Congressman will be available, 8 to 8:45 a.m., for the next two weeks; also the Second Avenue storefront where he will be on Friday afternoons; also a phone number to call “for assistance anytime during the new year.” I doubt that even a Congressman could convince Abercrombie & Fitch’s computer than I am not Mr. Steiner who owes them money, but the idea that an elected official is out there in near- zero weather asking questions is enough to cheer a New York voter’s heart. (Is Mendel Rivers standing around at country crossroads asking constituents how he can help?)

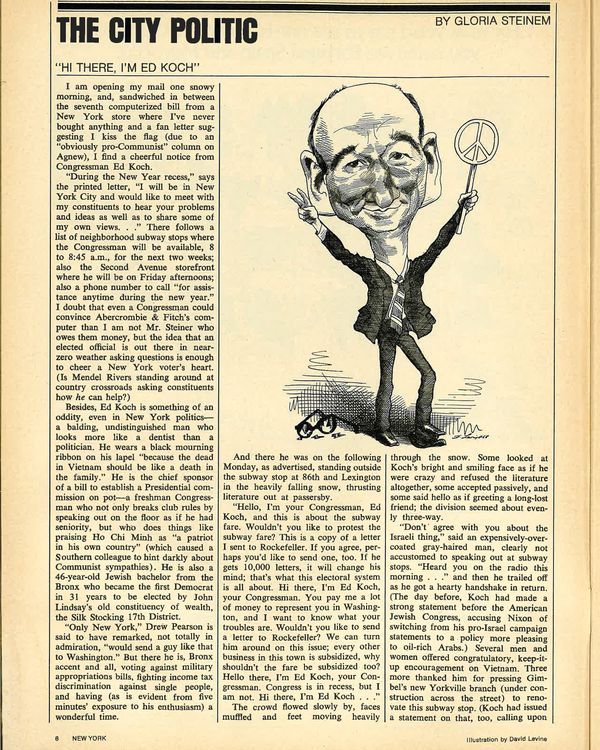

Besides, Ed Koch is something of an oddity, even in New York politics — a balding, undistinguished man who looks more like a dentist than a politician. He wears a black mourning ribbon on his lapel “because the dead in Vietnam should be like a death in the family.” He is the chief sponsor of a bill to establish a Presidential commission on pot — a freshman Congressman who not only breaks club rules by speaking out on the floor as if he had seniority, but who does things like praising Ho Chi Minh as “a patriot in his own country” (which caused a Southern colleague to hint darkly about Communist sympathies). He is also a 46-year-old Jewish bachelor from the Bronx who became the first Democrat in 31 years to be elected by John Lindsay’s old constituency of wealth, the Silk Stocking 17th District.

“Only New York,” Drew Pearson is said to have remarked, not totally in admiration, “would send a guy like that to Washington.” But there he is, Bronx accent and all, voting against military appropriations bills, fighting income tax discrimination against single people, and having (as is evident from five minutes’ exposure to his enthusiasm) a wonderful time.

And there he was on the following Monday, as advertised, standing outside the subway stop at 86th and Lexington in the heavily falling snow, thrusting literature out at passerby.

“Hello, I’m your Congressman, Ed Koch, and this is about the subway fare. Would you like to protest the subway fare? This is a copy of a letter I sent to Rockefeller. If you agree, perhaps you’d like to send one, too. If he gets 10,000 letters, it will change his mind; that’s what this electoral system is all about. Hi there, I’m Ed Koch, your Congressman. You pay me a lot of money to represent you in Washington, and I want to know what your troubles are. Wouldn’t you like to send a letter to Rockefeller? We can turn him around on this issue; every other business in this town is subsidized, why shouldn’t the fare be subsidized too? Hello there, I’m Ed Koch, your Congressman. Congress is in recess, but I am not. Hi there, I’m Ed Koch …”

The crowd flowed by, faces muffled and feet moving heavily through the snow. Some looked at Koch’s bright and smiling face as if he were crazy and refused the literature altogether, some accepted passively, and some said hello as if greeting a long-lost friend; the division seemed about evenly three-way.

“Don’t agree with you about the Israeli thing,” said an expensively overcoated gray-haired man, clearly not accustomed to speaking out at subway stops. “Heard you on the radio this morning …” and then he trailed off as he got a hearty handshake in return. (The day before, Koch had made a strong statement before the American Jewish Congress, accusing Nixon of switching from his pro-Israel campaign statement to a policy more pleasing to oil-rich Arabs.) Several men and women offered congratulatory, keep-it-up encouragement on Vietnam. Three more thanked him for pressing Gimbel’s new Yorkville branch (under construction across the street) to renovate this subway stop. (Koch had issued a statement on that too, calling upon President Bruce Gimbel to “take the initiative in illustrating how the business community and the city should work together,” and noting Gimbel’s inevitable profit from the stop.) Most just said hello, appearing startled to see this apparition in the snow.

The two aides handing out more literature nearby weren’t even doing the step-right-up-and-meet-your-Congressman kind of ballyhoo. They weren’t presenting a hero — just a guy with a big smile, a long nose, and a lot of chutzpah. “Hello, I’m your Congressman. I can’t do it alone, but together we can change your lives. Wouldn’t you like to write Rockefeller about the fare? Hi, I’m Ed Koch. Let’s sock it to Rocky!” The tone was unflagging, determinedly cheerful. One could see why he was still (and today turned out to be his 46th birthday) a bachelor. His constituents were his children; and politics, no matter how tedious the endless talking and public exposure might seem to others, was, to this lawyer son of an immigrant fur manufacturer, a full, rich life.

The one old woman who stopped to talk because she “didn’t like that last thing,” got his full and sympathetic attention. “That last thing” turned out to be Koch’s recent and controversial visit to American draft resisters in Canada, and the old woman had a grandson in Vietnam. “If those yellowbellies don’t even want to help,” she said, tears in her eyes, “then I don’t want to help them!”

Patiently Koch explained that there were almost 60,000 young Americans in Canada already, and Canadian officials were expecting (with pleasure, as the Americans were generally talented and welcome immigrants) as many as 150,000 more before the war was over. Shouldn’t we consider what options these young men would have when the war was over? Shouldn’t other young men be able to decide according to conscience? Even if they are drafted, couldn’t they be allowed to volunteer to go to Vietnam? Koch wasn’t advocating a correct leftist position, but trying to make contact with the woman, explaining that there were historical precedents for these solutions. In the end, she still may not have understood the “yellowbellies,” but she was feeling friendly toward Koch. The tears dried. She said, “I agree with everything else you’ve done.”

Warming up over coffee at the end of this daily marathon, he discussed his conclusions about constituent feelings. “Vietnam is still the major and overriding issue,” he said, “maybe not with Nixon’s people out there, but it is with mine. They’re horrified that it’s continuing, and they understand that the war — not welfare or Black people — is the real reason for high taxes and inflation. My district is probably exceptional,” he added with satisfaction, “but they really want me to be independent and speak out on the big issues.”

Other problems he is asked to solve tend to be personal: getting help from the Army in locating a constituent’s son who wasn’t writing home, speeding up the Immigration Department, aiding small merchants who are getting squeezed out of the neighborhood by high rents. But it is this kind of personal concern — in the form of resentment over the subway fare and the Long Island Rail Road — that he thinks might defeat Rockefeller this time around.

Koch’s main efforts in Congress have centered on cutting appropriations for Vietnam, ABM, and MIRV; reforming the draft; sponsoring a $10 billion Urban Mass Transit Fund bill; arguing for marijuana reform and tax relief for single people. The flood of facts concerning each of those was well ordered, and I wasn’t surprised to see a card full of notes nestling next to his coffee cup. For an interview with a local reporter, no politician except the enthusiastic Ed Koch would make careful preparatory notes. What with his talking and my scribbling, we never got to the coffee.

The last burst of facts was about his weekly routine. Every Monday morning, he gets up at 5:40, leaves his Village apartment at six, and gets the seven o’clock shuttle to Washington, where, among other things, he answers 100 constituent letters a day. Thursday night he’s back for three days of meetings, street-corner and otherwise. Newsletters at $1,600 a mailing are paid for out of his own pocket. He’s crazy about his staff of 11, whom he considers outstandingly competent. The worst thing that has happened to him so far was being forced by social pressure into shaking hands with the President. (“I really didn’t like the guy, but I told myself, well, he was a constituent. When he heard my district, he said, ‘There’s a lot of money there!’ What a crass guy.”) Koch is pragmatic and has political ambitions — Senator or Governor, his friends say. That future may be endangered by his replacing William Ryan as court jester of the left in Congress, but Koch clearly doesn’t think it’s happening. He sees progress, and his enthusiasm makes others, at least for the moment, believe it, too.

We take the subway downtown together, and I leave him smiling into the middle distance, concentrating already on the next appointment in a crowded day. (He has proudly shown me his appointment card. It ends with Long John Nebel, a few hours before dawn.)

Let me know if you need anything,” he says, as happily as if the phrase had never been said before. “That’s why I’m here!”