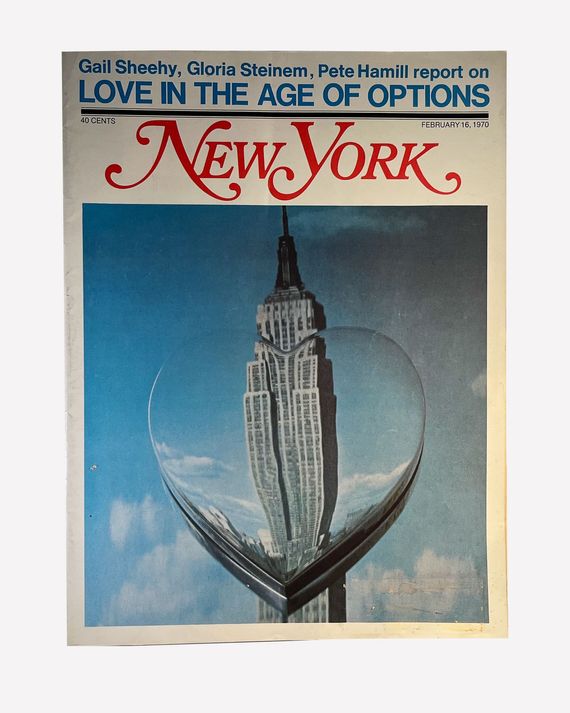

Editor’s note: This story first appeared in the February 16, 1970, issue of New York. We are republishing a selection of Gloria Steinem’s writing from our archive to celebrate her 90th birthday.

New York is a Distant Early Warning System for art, fashion, industry … and for love styles.

Are Jewish-Christian marriages still an oddity in the country clubs of the Midwest? Here, religious differences are barely noticed anymore, and we’ve progressed to another question: who’s got the money? Is interracial dating still a phenomenon confined mostly to campuses? In New York, we have already figured out that white woman–Black man is the most usual combination, but that the reverse works out better in case of divorce (mother and child being more likely to match). Are mothers in Detroit worried about teenage marriages and college drugs? Here, a third of all out-of-wedlock babies are born to girls still in their teens, and some schools hold special graduation ceremonies for pregnant students. By this summer, the number of “child addicts” (heroin users, often under 16) is expected to reach 100,000. Avant-garde women struggle for alimony in the rest of the country. In New York, avant-garde women in the Women’s Liberation Movement struggle against dependence on alimony, and run ads like this one from The Village Voice: “If your ex-wife’s an alimony junkie, we’ll try to rehabilitate.”

Of course, in the midst of all this change, there are still islands of ethnic calm. Week-long Italian marriage celebrations, Chinese courtships carried on by letter, young Greek men going home for a bride, Puerto Ricans who won’t marry across island feuds — all these anachronisms can be found side by side with the unmarrieds who live together and the marrieds who are resting between divorces.

But the city creates love styles of its own. In courtship, nobody much meets the parents anymore. They’re more likely to meet the children by some other marriage. White husbands cheerfully explain the parentage of assorted children in terms formerly reserved for horses. Black mothers assume such questions come from welfare investigators, and clam up. It has been suspect for years for two men to live together. Now two women are beginning to get strange glances: more so, for instance, than male-female roommates who aren’t married at all. City politics are famous as a meeting and dating ground. There’s a deep suspicion that, in New York, the candidate with the largest number of sexually viable volunteers is the one who wins.

Even the sacred month of June has gone out the window as far as marriages are concerned. In the past three years, August has crept past it in the marriage license offices of most boroughs: August is the month of business vacations in this town.

The whole country is becoming urbanized. And so is love.

On the Upper East Side, there are tests to be passed: concentric circles of intimacy. The girl in the Rich Hippie clothes and the suede-jacketed man looked each other over, exchanging symbols with tribal care. (“Sugarbush,” “Whenlwasatboardingschool,” “McCarthy,” “Bloomie’s,” “The New York Review of Books.”) They ferreted out and discussed all their mutual friends: his from Yale, class of ’59; hers from one semester at Finch six years ago. “I went to see Oh! Calcutta!,” he said, sending out the first discreet sexual signal, “but it was boring.”

Then they went to bed, an exercise slightly marred by his habit of keeping his watch on (Cartier, she noted, but was annoyed just the same) and her determination to seem inexperienced. The next morning, they exchanged the numbers of their unlisted phones.

By the following weekend, he had met her two blond children by a post-debutante marriage (who lived, as befits the privacy of a young divorcée, on the top floor of her brownstone duplex with their nanny), and she had seen some color photos of his children, the athletic image of their 30-ish, Vassarish mother carefully cut out. When the standard dinner invitations arrived that week, each dismayed his or her singles-seeking hostess by asking if the other could come along. Soon telephones were buzzing as friends discussed the merits of this latest pairing-off.

She took him to an Off Broadway play, and he pretended to like it. Here is a man, she said to herself, who shares my interests, not like my husband, who thought only of his import-export trade. (But who did, she had to admit, take his watch off and generally seem more interested in bed.)

He took her to dinner and dancing at Raffles, a club his former wife had pronounced poorly ventilated and overpriced. Opening a new stage of Confidence-Sharing, he explained the particulars of his separation agreement: a bitter complaint about the size of his alimony payments came with the steak Diane, and a list of personal possessions kept by his wife (a favorite desk, all the best records, the sailboat — his sailboat, for chrissake) accompanied the fraises parisiennes. Why, his new companion thought to herself as she nodded and smiled, do divorced men, no matter how rich they are, complain all the time about records they lost? The alimony they are paying? A form of bragging, she decided, and refrained from telling him that her alimony was even higher.

Here is a girl, he thought approvingly as they got up for their First Dance Together, who would never take advantage of a man.

Monday morning they exchanged numbers of their private unlisted phones: the ones with no nosy answering service.

Tuesday they got their first joint dinner invitation, the hostess slyly noting that she was sure they would want to come à deux.

Wednesday they dressed in their brand-new old clothes and sat for hours at Elaine’s over lobsters, wine, and their First Sexual Confidences. He told her about his marriage and youthful affairs, exaggerating just a little. (Obviously, this unawakened flower — so much less aggressive than his wife — needed to learn what real love affairs were all about.) She told him the same, minimizing quite a lot. (How could she tell a man whose idea of lovemaking was ten minutes before a snoring good sleep about a husband who, after a successful business deal, had kept her awake all night long?) They decided that they were officially In Love.

Only three more symbolic acts remained. His children met her children. Their various divorced and remarried parents met for a drink. And finally — much the most difficult — a suitable place to combine closets and possessions was found within the boundaries of 60th and 81st Street, between Fifth Avenue and Third.

They see less of each other now that they are married. She goes to exercise class every day, and he relieves work boredom by tinkering with a new sports car. In the evening, they go to dinners and benefits where couples are seated far apart. But she is pleased that the strain of being the Extra Girl is over, and he is generally happy to spend weekends with racing car magazines and sports programs, knowing that the charade of Adventurous Bachelorhood is past.

The other day, while buying some shirts for her new husband at Meledandri (the same style, size, and shop that her first husband had used), she realized that these few East Side blocks had contained her birth, growing up, two marriages, and the birth of her children; that the same could be said for both husbands (whom she thought of more and more as a pair) and for most of their friends.

In fact, she thought, depressed by the limitations of her days, there’s really not much difference between me and all those housewives who watch television and buy shirts and never move outside Queens.

She looked down at the toes of her $120 Italian boots and brightened. But no one in Queens, she thought with satisfaction, would ever believe it.

_

At LEAP (the Lower Eastside Action Project), a group of Puerto Rican boys is meeting with some writers and sociologists who have been concerned with New York’s ghetto problems for a long time. The Puerto Ricans, who are trying to pull themselves up from the roughest kind of street life, considered this meeting an important occasion and therefore put on jackets and ties. They are insulted by the old pants and frayed sweater of Paul Goodman, the radical social critic; they think he didn’t have enough respect for them to dress up, and this takes a while to explain.

Goodman, on the other hand, seems upset by their desire for high school diplomas, “good” jobs, and the materialistic lifestyle of the middle class. He talks to them on “the culture of poverty”: the non-middle-class satisfactions they already have in communal living, street culture, and “good sex.”

“Meester Good-mon,” says one young Puerto Rican finally (significant emphasis on the “Meester,” though they have been asked to call him Paul), “Meester Good-mon, you ever have ‘good sex’ and a cockroach fall on your back? You ever have ‘good sex’ like dat, Meester Good-mon?”

_

Leo is a Polish taxi driver from the Bronx, about 50 years old, the father of one married daughter and one son in City College, and today is his wedding anniversary. A color snapshot of a plump, 50-ish woman with an exceedingly big nose is Scotch-taped to his dashboard. The baby she is holding is their second granddaughter, Leo explains, and the ugly, imitation-brick house in the background has been their home since their wedding trip to the Jersey shore 25 years ago.

He starts this conversation by asking his passengers, a tall black man and a pretty white girl, if they are married. They say they are not. From there on, it is pretty much a monologue.

“I don’t know what I would have done without that woman there,” he says, gesturing toward the snapshot. “From the day we got married, she’s made her own clothes, and made suits for me. I got sick and things were bad, so she started up a little dressmaking business in our living room. Made quite a lot of money, too, but she would have made herself sick working if I hadn’t stopped her. She didn’t want me to come back to the cab too soon after the operation. She’d work in the middle of the night so she wouldn’t worry me, and I’d wake up and take the fuses out of the box so there would be no lights, and she’d have to stop.

“The kids are beautiful and the grandkids are beautiful; I miss them when they’re not around. But I tell you, if anything happens to that woman, it better happen to me, too. She knows my thoughts and I know hers. We don’t have to talk anymore, we can just look. And I get such a kick out of pleasing her. Tonight, for instance, I’ve arranged a little surprise party at this bar in the neighborhood, and I’ve got spareribs for everybody, and real Polish kielbasa. I can’t wait to see her face. I’ve invited everybody from the neighborhood, and her mother’s family from Staten Island, and my kids and I bought her a beaver coat. She’ll look bee-you-tee-ful in that coat! I’m no saint, you understand, but I get as much kick out of buying things for her as I do for myself.”

His passengers get out at the Eighth Street Playhouse, smiling and saying good-bye to this lovestruck man they’ve come to know in a 20-minute ride. As the tall Black man pays him through the window, Leo says something that the girl doesn’t quite catch.

“Did I hear what I think I heard?” she asks, staring after the American flag sticker on the taxi’s rear window.

“Yeah,” the man says, shaking his head. “He said, ‘You two nice kids ought to get married.’ He said, ‘You’re what this country is all about.’”

_

In spite of recent “liberalization” of New York State divorce laws, dissolving a marriage here takes more time and money than most middle-class couples can afford. Only the very poor, who are trapped here, and the very rich, who fear future claims on their money if divorces aren’t airtight, put up with the procedure that now allows grounds other than adultery but still takes two years. For everybody else, the overnight divorce trip to Mexico is still very much part of New York’s love styles, even though the legality of such divorces is still in question.

“The more people who do it, the more likely it is to be legal,” explains one hardened divorce lawyer. “Now, the only difference is that separation papers can be filed in New York and become effective after two years, with the Mexican divorce to cover you in the meantime.”

Three days to get married, two years to get divorced. When asked why the first shouldn’t be made more difficult than the second, those few New York legislators who will talk about it generally mutter something about the danger of illegitimate births going up. The mutter stops when abortion-law repeal or reform comes up, because the point is less humanitarian lawmaking, or even common sense, than avoidance of a political hot potato.

The more psychologically minded, however, think that Albany’s motivations are as much personal as political. Politicians tend to be even more repressed than most of the early-marrying middle class, since they can almost never get divorced and they worry more about blackmail and scandal. Therefore, they seem to enjoy, consciously or not, punishing those who are free to divorce; punishing the poor and the Black, whom they imagine to be sexually free; and punishing women (the liberated ones they can’t have, the repressive wives they’ve got), who must be made to suffer what 19th-century inequities the law can preserve.

When legislative sessions are over, the legislators gather across the street in the bar of the Hotel Ambassador. The discussion of sexual adventures they have had, or say they have had, or are hoping to have, is reported to be somewhat below the maturity of those in reform school dormitories.

“The two most sexually repressed places I know,” said one assemblyman’s secretary, “are the State Legislature and the lobby of the New York Hilton at convention time. It’s worth your life to walk through either one of them.”

A lawyer is sitting in his small office at a Manhattan publishing house. Since he is also the office Good Person and general ombudsman, he isn’t very surprised when Stella, the receptionist, comes in for advice. (Already that morning, he has steered one colleague to a clergyman’s abortion-referral service and advised a second on how to get clothes back from a hostile ex-roommate.) But he is surprised at the matter-of-fact way she states her problem: she is pregnant, and her boyfriend is still married to someone else.

Not that she wants an abortion. Married or not, both she and her boyfriend want the baby and consider abortion somewhat old-fashioned. They wouldn’t bother to get married at all were it not for the practical problems of giving the baby a birth certificate and a name. (They would really like to follow the hippie-commune practice of having the baby delivered outside a hospital by a radical young doctor or midwife so that the child is born “free,” without a social registration number of any kind. Regretfully, they’ve decided that this tactic — which takes care of all school, fingerprint, and draft problems in advance — is still impractical in the city.) What has brought Stella in for advice is a simple problem of cash. Neither she nor her musician boyfriend has much. In fact, both of them share all expenses and household chores, believing that this helps to break down the male-female stereotypes that would keep her in the kitchen and send him off to war.

So far, the lowest figure quoted them for a Mexican divorce is $1,000, and they just can’t afford it.

“Too much,” says the office radical sympathetically. “Four seventy-five is the real minimum — $225 for the Mexican lawyer and the rest for a roundtrip plane ticket to El Paso, motel, and food.” New York divorce lawyers, he explains, charge $500 for a simple phone call to arrange things in Mexico that should cost $50 at the most. Furthermore, as a man experienced in turning the system against itself, he figures out that their joint income tax return for the first year will more than pay for the divorce.

Stella leaves the office greatly cheered, bearing the good news to her boyfriend. The lawyer — rather flattered that she has chosen to confide her secrets in him — goes out to lunch.

“What about it?” asks the chief accountant. “Can you get Stella her divorce?” The elevator boy asks the same thing. Stella, the lawyer discovers, has discussed her problem — in her 23-year-old, un-hung-up way — with everybody in the office and her Brooklyn postman father besides.

The lawyer is only 36, but the years suddenly hang heavy. You can’t go home again, and even Italian receptionists from Brooklyn will never be the same.

_

In the world of expense accounts, company yachts, and decorative wives, big executives employ public-relations men to guide their extracurricular lives. The right charities, the right tailor and interior decorator, the right speechwriter, the right art-buying advice: all this goes into the PR man’s creation of executive image. The only trouble is that, once successful, the executive likes to believe the taste was his own, and the PR man gets quietly dropped.

To defeat this turnover problem, one distinguished PR man inserts himself insidiously, permanently, into the client’s love style. Is the executive’s beautiful wife bored to death with the endless stock deals and board meetings? The PR man will seat her discreetly next to the ski-champion son of another client. Is the executive married to the un-beautiful, un-chic wife of his youth who hasn’t quite “grown” with his career? The PR man will escort the radical daughter of a famous American fortune to the next charity party and guide the beautiful young thing gently toward his client with instructions to raise money for her “cause.” (Thus achieving full fringe benefit of client-education. “More culture has been acquired in bed,” the PR man is fond of saying, “than in all the world’s museums and theaters combined.”) Or he may introduce his client to a beautiful female executive, knowing that their leisure-time needs are about the same.

Unless pressed, he will not procure any actual hookers, however expensive and tasteful they may be. His clients know him as a man of high moral standards, and that’s one of his best selling points. Besides, the point of the exercise is to become the confidant of both parties, thus working himself inextricably into the fabric of their lives. And who wants to become the confidant of a hooker? No, the idea is to be the catalytic agent in all areas of a client’s career, and to absorb the stock tips, house-party invitations and endlessly renewed PR contracts that come as a reward.

“Say, what you need is my PR man,” one executive is forever saying in response to the troubles — any kind of troubles — of another. “He’s one of the few real gentlemen in the business.”

Gilda is 13 years old. If her eyes were not so empty and her smooth, cocoa-brown face so unfocused, she would be a very pretty girl.

Right now she is lying on a sofa bed in the 104th Street apartment of an aunt, and there is no sound except the hissing gas jets of the kitchen stove, the only heat in the three-room apartment. Next to her, wrapped in a clean blanket that once belonged to a hotel, is her 7-month-old baby, Joseph.

At least, his birth certificate and the welfare investigator call him Joseph. Gilda hasn’t accepted the name yet, because she’s still searching for a fine, romantic one, something never before heard of on 104th Street, something like the one her own mother, a 15-year-old girl who watched television during most of her pregnancy, picked up from an old movie about a beautiful goddess and bestowed on her baby daughter.

What stops Gilda is that it must be a man’s name. And what fine name can there be for a man? All she can think of is the name of the baby’s father (which she hasn’t told to anyone, for fear the welfare investigator will try to get him back), or the name of the big man from Honduras her mother is living with now, or the names — fearful names! — of the street boys who chased kids to school, and stabbed a boy who wouldn’t give them his money. She keeps coming back to the baby’s father’s name, but he once told her it carried a voodoo curse, and she can’t think of a way of making sure.

Not that she hates him, or loves him. She can’t even remember his face quite right after all these months. What she does remember is the taste and feel of summer days with him on the roof of the school, or walking down the street next to him with a can of Pepsi in her hand. What she remembers most is the feeling of being paid attention. Daydreaming through the icy days now, she thinks about that feeling and forgets the baby lying there. Sometimes she looks down at his dull, quiet eyes, and she can’t remember who he is.

A black lady nurse has told her to hold him and talk to him or he won’t grow up the way he should, he won’t learn. She tries to remember this, but with her aunt at work and the cousins at school, she slips into her daydreams for hours.

The nurse told her not to leave milk or food on the baby’s face, because that might attract rats. She told her not to be ashamed or worried, that there were thousands of girls like her in the city who had babies when they were too young.

“Okay,” Gilda said, “I won’t be ashamed. But my aunt is ashamed, and my teachers are ashamed, and I can’t go to school or out in the streets with the baby to watch.” The nurse, who always looked like she was holding her breath to keep from smelling something bad, seemed mad about that, and started asking questions of her aunt. Did all five kids have the same father? Had she ever been legally married? Was Gilda’s mother her real sister or half-sister? She was writing the answers down in her little book for a “report.” Gilda’s aunt threw the nurse out.

The next day, Gilda put her old school clothes on and went out to the street for company, but only a few pushers and old women with shopping bags were around. And it was so cold that two policemen had built a fire in a metal drum. When she got back upstairs, there was a rat the size of a cat sitting right in the middle of the bed. Joseph was okay, but Gilda dreamed about rats eating his face away after that. In the last two months, she hadn’t so much as set foot in the hall. Sometimes, she thought she couldn’t remember how to talk. She even missed the visits of the nurse, and she hadn’t felt easy with that nurse at all.

If there are thousands of girls like me, she thought, where are they? What do they do? How can they get through a whole day?

_

St. George’s Episcopal Church still rises grandly in the center of Bedford-Stuyvesant, a remnant of the neighborhood’s European past. The weddings there are as flower-banked and status conscious as ever, but now the couples walking down the traditional aisle are black.

Today’s wedding party includes two maids of honor, 12 bridesmaids, 20 ushers, two veil-bearers, the schoolteacher bride herself, and the nervous groom, blinking through his glasses like the city clerk he is.

“Such a beautiful wedding,” say all the ladies in satin hats as they gather at Brooklyn’s Granada Hotel for a big reception. “Such a perfect couple,” say all the girls who went to City College with the bride, knowing that a prettier girl could have got a doctor or lawyer instead.

“Such a bad scene,” thinks a friend of the groom, the only man present wearing a Dashiki. “Nobody but nobody is more middle class than the Black middle class.”

But he doesn’t say it out loud. He grew up in this neighborhood too, and he knows how hard the bride’s mother worked at “day work” in white women’s kitchens to keep her five children off the streets and in school. He knows how the bride’s father brought his longshoreman’s pay straight home every week and got back just enough for a Friday night haircut and Saturday night beer. He knows all the scrimping and saving and cheap cuts of meat and castoff white people’s clothes that went into a down payment on the old brownstone the family was finally able to buy, making them “boojie,” in the militant’s vocabulary — part of the Black bourgeoisie.

But there are some things he still holds against them, and against the bridegroom, too. The pride in being West Indian, for instance, that made them display a picture of Queen Elizabeth on the wall and act superior to Blacks from the South, even when they were scrubbing the same kitchen floors. Or their insistence on standards of “good family,” “behaving like gentlefolks,” and “steady, good-future jobs.”

“How much did all this cost them?” the young militant wonders sadly, looking around at the cake and musicians and new clothes. How much could have been used for the Panthers’ breakfast program (many of the guests here would think of them as “troublemakers”), or even for the reward of these old people who had worked so long? He remembered an old grandmother who had died slowly in Bedford-Stuyvesant, crying silently for the sunny island of her youth. But she wouldn’t let her grown children pay for a trip to Barbados, and she lectured her grandchildren on the value of “scrubbing your knees and getting to school on time” until the end.

He watches the bridegroom dancing with his bride, and a photographer (another $50, the militant calculates) capturing this moment for the overpriced white plastic album that would soon be gathering dust in their tiny apartment, also overpriced. The bride would keep on teaching school, and the joint savings account would fill slowly. There would be two or three scrubbed children, no swearwords or animals allowed in the house, and a level of funkiness and soul about equal to that on Cape Cod.

“It’s the victory of class over race,” he thinks, watching the squealing bridesmaids compete for the bridal bouquet. “If they could see this in Scarsdale, they wouldn’t worry about a thing.”

Three semi-intellectual, semi-rich young white matrons are having coffee after a chance meeting at the cheese counter of Zabar’s. They discover, while evaluating the audience-stimulation possibilities of Oh! Calcutta!, that all three are having, or have had, affairs with their analysts.

The most sociologically minded of their number has it all figured out.

“Psychiatrists,” she says firmly, “are the male geishas of our time. I mean, the women who go to analysts usually have empty days on their hands, right? And Freud was too male-chauvinist to figure out we needed professions as well as sex, right? So these analysts get a lot of attractive women in their offices and encourage them to talk about their sex lives, and, well, one thing leads to another. Those poor bastards are usually stuck with the wives who put them through medical school anyway, if you see what I mean.

“Now, the beautiful part of all this is it’s perfect for the woman. She gets sex and someone to listen to her with a little sympathy — the two things she’s probably missing in her marriage. Intelligent companionship in the daytime. What husband could object to his wife’s appointments with her doctor? Besides that, she’s sure he’ll never tell, because it would be terrible for his professional reputation; I mean, transference just isn’t supposed to lead to that. When she’s tired of the thing, all she has to do is plead guilty or play on his guilt at being unprofessional and cancel her appointments. She might even get him to refer her to another psychiatrist. And, voilà! a whole new romance!”

The other two digest this information silently for a while, realizing the importance of such a formulation.

“You know,” says one finally, ’“you’re absolutely right. I wonder how many women in the city have made the same discovery?”

“I don’t know,” giggles the third, “but if our husbands ever figured out how much men and women think alike, they’d go right up the wall!”

_

He is a successful hotel executive with an odd reputation among women. (Rumors of beatings and lovemaking recorded by bidden cameras abound.) He is also a “liberal” political activist whose hatred of draft-evaders and longhaired peace-marchers no one can quite understand. (“But I can,” said a girlfriend who had suffered at his hands. “His idea of the male role is sadist, and those kids undermine his whole thing when they say that men don’t have to love war.”)

His new ladyfriend is a beautiful, gently bred divorcée with two daughters, and no one can quite see what she sees in this rough, self-made man. (“But if you knew her first husband,” said a socialite friend, “you’d understand it. She whispers and minces and puts down ‘unfeminine’ women because she’s a genuine, dyed-in-the-wool masochist. He beat her, too, but apparently not enough.”) Currently she is writing a book on decorating, but the text is strangely full of what working women and Women’s Liberation girls are “doing to themselves.” In fact, the subject of non-subservient women is the one thing sure to crack that ladylike exterior with a rash of adjectives and rage.

The divorcée and the hotel man are about to be married. They seem gloriously masculine-feminine together, like Beauty and the Beast.

“You could laugh, if it didn’t make you feel like crying,” said the socialite friend as they made an entrance into Sardi’s. ”They’re the perfect sadomasochist pair.”

_

Like thousands of girls who arrive in New York each year, Catherine came in search of freedom. She has found a little of it, plus a successful photography career. Each year she puts off marriage, but still doesn’t think in terms of “career.” What that produces is a state of temporariness, and this state, she has decided, is the chief characteristic of New York.

“Everybody has a dream,” she said. ”Nobody plans. Maybe that’s especially true of all the single women here — women aren’t taught to plan, they’re brought up to think decisions are made for them — but it’s true of the men and the children, too: Tomorrow your stock investments might go up, you might get a big part in a play, your article might get bought for the movies, you might meet a terrific new lover at some party, your company might get bought up in some big-money merger. If you live in a ghetto, you play the numbers because that’s the only dream.

“It messes you up a little to live on hope of bigger love, bigger success. But I like it. It’s the hope in the air that attracts everybody here.”

She looked around her furnished apartment at the debris of contact sheets and developing pans. She is 27 and in that state of expectation that, when you stop to examine it, turns out to be happiness.

“Still,” she said, “I wish I’d known it would be like this. I could have bought some lamps.”

_

No one can be sure what the end will be; which of these love styles are here to slay. But cities are the experimental centers. Whatever happens, New York will be the first to know.