Editor’s note: This story first appeared in the April 8, 1968, premiere issue of New York. We are republishing a selection of Gloria Steinem’s writing from our archive to celebrate her 90th birthday.

Ho Chi Minh was a waiter in the Bronx.

He taught poetry at UCLA before the

war.

He taught guerrilla tactics at American army camps.

I’m sure he worked in a Chinese laundry when he was young; that’s what I’ve always heard.

Sometime in the ’20s, he had a photography shop in Harlem.

Sometime in the ’30s, he lectured on Communism at CCNY.

Of course, nobody wants to admit it now, but he grew up on Mott Street.

He washed dishes someplace downtown and was very badly treated, which is why he hates us.

New York is his favorite town.

These are only some classics from a large collection of rumors. Usually they sound less like fact than a retreat to sick jokes (Ho, the brilliant leader we can’t defeat, becoming momentarily manageable as Ho the laundryman) but they have been multiplying since the first American soldiers were sent to Vietnam. Most of them center mysteriously on New York.

And most of them center on Ho Chi Minh’s life before 1945, which makes them difficult to track down. Since the last days of World War II, he has been in highly visible conflict with the French or Americans or both, but before that, he lived the wandering half-life of an expatriate revolutionary, condemned to death in absentia by the French colonial regime. Under at least eight names other than his own and variously disguised as a peasant, a Buddhist monk and “a Chinese journalist from Vienna” (the last was engraved on his visiting cards às late as 1941), he appears and reappears as an increasingly mysterious and powerful figure.

Twice in his 78 years he has been declared dead, once so convincingly that the French Sûreté lost track of him for a decade. They discovered that Ho Chi Minh really was their much arrested and occasionally dead revolutionary only after comparing old photographs with those taken at his 1945 presidential inauguration in Hanoi. The convolutions of his ears were the same; as dead a give-away, apparently, as fingerprints.

So it’s no wonder that few biographers have tried to pin down some early sojourn in New York. Or that those who do mention it disagree. He was or was not in America sometime between 1911 and 1918; when he did or did not land in New York, Boston, or San Francisco; and he jumped ship for two years, wandered around for a few days, or never got off at all.

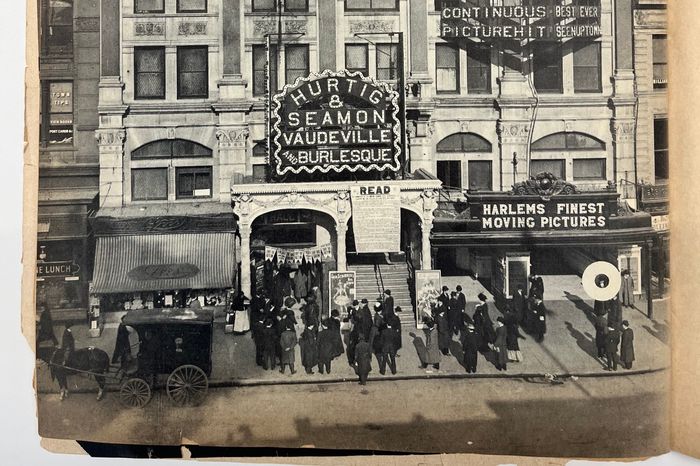

A few American sources refer to his living in Harlem—usually because of articles he wrote about the Negro problem while in Paris and Moscow—but everything in his anti-racist tracts could have come from research. Besides, scholars find the Harlem reference too pat, and a little anachronistic. Why would Ho travel to a neighborhood that was, in the period he was supposed to have been there, difficult to reach, and overwhelmingly white middle class?

Why indeed?

Biographical details are still difficult to get, even though the almost continual war in Vietnam has kept Ho in the spotlight for the past 23 years. When Bernard Fall inquired directly about his background, Ho smiled and said, “I like to hold on to my little mysteries.” David Schoenbrun once asked where he had been in his youth. “What is more important,” said Ho, “is to know where I am going.”

But the clues are tantalizing. Miami newspaper editor William Baggs, probably the last American to interview Ho, was so struck by the familiarity in Ho’s questions about New York that he tried to document a visit here, but without success. (Ho had asked what was going on in New York, referred to “Chicago bandits” and “hold-ups” in the course of describing Vietnam’s situation, and seemed oddly at ease with Americans.) Other interviews yield little things: certain archaic American slang phrases; an un-Asian tendency to slap Americans on the back; references to “your big buildings” or “those crowded streets”; an attitude when speaking of the city, as if he were picturing it in his mind; even a lifelong fondness for American cigarettes. (When Ho came out of the jungle in 1945, many of his own men had never seen him. They recognized this frail old man as “no ordinary peasant” only by his shirt pocket from which protruded a pack of Camels.) Most of all, there was the occasional little non sequitur question, “How is New York?”

Occasionally over the years, he has revealed a small store of facts about himself. That he regretted never having a wife and family, for instance. (Until that was reported, many people said he had married while in Moscow.) Or that he grew vegetable gardens, even at his makeshift headquarters in the jungle, or was fond of champagne (he always served it at the signing of an agreement), or considered his typewriter the one possession he could not get along without.

These little confidences were always brief and accidental, as if they just happened to come to him in the midst of more important talk, but it seemed reasonable that somewhere, sometime, he had reminisced about a trip to New York. The only answer was to read everything findable, talk to those French and Americans he had met, and hope that the American rumors could be tracked down.

The odd thing was that most of them turned out to be true, or to have some truth in them, as if his biography were coming down in the oral tradition. He had been a waiter, not in the Bronx, but on a French steamer that shuttled vacationing colonials from Haiphong to Marseilles.

The dishes he washed were not here but in London; possibly in the kitchens of the Carlton Hotel where he later became an assistant pastry cook. He also shoveled snow for London schools, read Shakespeare and Dickens, listened to the Fabians, watched the Irish uprising with interest, and studied the literature of revolutions.

The Harlem photography shop of rumor was in Paris during World War I. (“Have your photographs retouched at Nguyen Ai Quoc’s,” said an ad in a workmen’s magazine. “A lovely photograph in a lovely frame for 45 francs.”) But photography was a meager living, a necessity. Most of his time was spent on Le Paria, an anti-colonial magazine he published, wrote and illustrated; impassioned speeches on the miseries of his countrymen; all-night discussions of socialism; reading French novelists, especially Zola; and an occasional rally for Sacco and Vanzetti. He also taught Communism and poetry, not separately in America, but combined in Moscow. At the Lenin Institute, he sometimes gave his lectures on the plight of colonial peoples in verse. The rumor about teaching guerrilla tactics at American Army camps comes from two sources: Ho did help train Kuomintang troops in guerrilla fighting, and, for two years at the close of the War, he worked with American OSS forces against the Japanese.

That Ho was once something of an American hero is no secret, but nobody talks about it much anymore. With small groups of Americans who were parachuted into the jungle, Ho and his Vietminh forces fought against the Japanese occupation, and rescued downed American fliers during 1944 and 1945. Some of the OSS men got to know him well. They weren’t all political, or even knowledgeable about the area, but they did come to sympathize with Ho’s anti-colonial cause as did President Roosevelt at the time, and they now remember him with affection and respect. In 1946 when the French were fighting to take back their colony, one lieutenant was banished from Paris for advocating support of Ho. (And America, fearful of Ho’s Communism and of losing France in the European military alliance, played down its anti-colonial sympathies.) In 1964, two former OSS men who knew Ho and felt we were “pushing the old man too hard” offered to act as go-betweens, but the State Department declined. “I know he’s a Communist,” said one of them, now a prosperous businessman, “but I still think he’s a nationalist first. He’s the closest thing to Gandhi we’ve got left.”

These temporary soldiers did get to know Ho Chi Minh probably better than any other Americans. And he did talk to two of them about New York.

That confirmation, plus David Schoenbrun’s memory of a 1946 talk with Ho, a prophetic out-of-print book on Vietnam by Yale political science lecturer Joseph Starobin, remarks by the widow of Indian Communist M.N. Roy, and a patient woman at the French consulate who looked up shipping records—these sources, combined with various accounts of the period, yielded the following:

In 1915, sometime before his 25th birthday, Ho Chi Minh arrived at the docks in New York. As mess boy on a French merchant ship, much larger than the steamer on which he had first left Vietnam, he had already visited many African and European ports. In each country, he looked for the same thing: a sympathetic hearing for the problems of Vietnam.

He was still known by his servant’s name of Ba, but on shore, he tended to wear dark Western suits with high-collar shirts, and to resume his real name, Nguyen Tat Thanh. Small, beardless, and quiet, he went about, according to Jean Lacouture’s description of a police photograph taken near that time, with “a small hat perched on top of his head, looking delicate and unsure of himself, a bit lost, a bit battered, like Chaplin at his most affecting.”

His French was good, though not as confident as it later became at Paris political meetings, and his English rather scanty, but he was determined to make the best use possible of his two-week shore leave.

America, after all, had made a successful revolution. “You Americans ought to remember,” he said later when explaining the power of Vietnamese nationalism, “that a ragged band of barefooted farmers defeated the pride of Europe’s best-armed professionals.”

New York Age and Max Eastman’s Masses magazine were likely reading then, but the newspapers he mentioned later were the “bourgeois press” picked up in Europe. If he found his way to the radical social group of the day, as he had in other cities, it would have been Mabel Dodge’s famous 23 Fifth Avenue salon near Washington Square. Carl Van Vechten had begun to bring in West Indians and Negroes, not always to the social pleasure of Miss Dodge. Walter Lippmann, then a socialist, attended often, and doesn’t remember any small South Asians wandering in; but then neither does Malraux, who met Ho Chi Minh with Borodin in China. The young Ho was not a visually memorable man.

He did make a pilgrimage to the Statue of Liberty, a sight to which he now indirectly refers. “Tell, me, gentlemen,” he said reproachfully to American visitors last year, “is the Statue of Liberty standing on her head?”

The visit to Harlem turns out to be true, but almost accidental, and not for the reasons now given. He wasn’t asking for the Negro district (at least, not in this instance), but for the way to Columbia University. Traveling uptown on the Eighth Avenue Elevated, then the only fast transport, he may have discovered that lodgings in Harlem were cheaper, and for a rather odd reason: Negroes had just started block-busting.

Obeying Booker T. Washington’s mottoes, “Get Some Property” and “Work and Money,” they were buying up buildings as individuals, churches, and realty companies. Harlem was selected only because it was too far away for many whites, and contractors had over-built, leaving many brownstones and apartment buildings unrented. Negroes had been arriving for some nine or ten years, but the total atmosphere was still overpoweringly white and upper-middle-class. James Weldon Johnson, the Negro historian, describes white families fleeing “the invasion” if one Negro face appeared on the block.

Ho audited some Columbia classes, and tried without much luck to interest people in the fate of a far-off people. Though San Juan Hill in the West 60s was still the Negro center, a hair-straightener millionairess named A’Lelia Walker was beginning an uptown salon. It’s doubtful that Ho would have found it to his taste (the crowd was more theater and business than intellectual), but no one remembers him.

Whoever the people he talked to, Ho remembers them now with disappointment. He had looked to America as an anti-colonial country, but no one was interested in anti-colonialism. With good intentions and bad results, we were just sending Marines to bring order out of anarchy in Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Three Mexican names—Zapata, Pancho Villa and General Carranza—were frequently in the headlines, and President Wilson seemed to be on the verge of a reluctant war with one or all. Europe was on the verge of a war, which Americans were trying to ignore. Negroes themselves were much disillusioned with Wilson, and a wave of segregation was causing even those in the post office department to lose their jobs. Whites worried about the beginnings of a new movement for “the Yellow Peril and the Black Peril to join hands round the world.”

It was, in fact, a period not unlike now.

But Ho remembers other things, too: a family he boarded with, their names long forgotten, who treated him kindly; the crowds and vitality and streets-paved-with-gold that he saw here. Perhaps even for President Wilson, to whom Ho, in rented suit and bowler hat, appealed personally at the Versailles Peace Conference four years later.

He reads American authors, welcomes individual Americans in a way that one cannot imagine, say, a Frenchman welcoming Germans; and draws what seems more than a politically advantageous line between Americans and their leaders.

He is an old man now, perhaps no longer in total control of the Vietcong, or even of North Vietnam’s rival forces. But every once in awhile, he still peers quizzically at some visiting American, and says, Tell me. How is New York?”