Editor’s note: This story first appeared in the January 5, 1970, issue of New York. We are republishing a selection of Gloria Steinem’s writing from our archive to celebrate her 90th birthday.

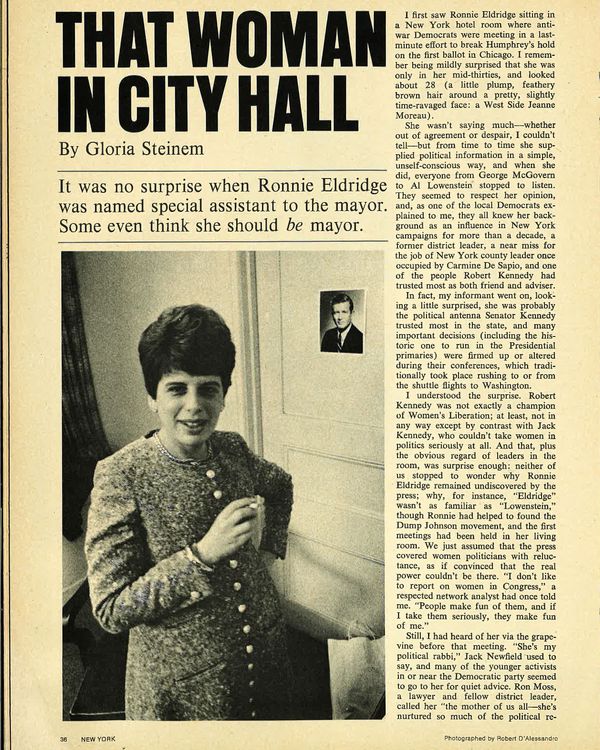

I first saw Ronnie Eldridge sitting in a New York hotel room where antiwar Democrats were meeting in a last-minute effort to break Humphrey’s hold on the first ballot in Chicago. I remember being mildly surprised that she was only in her mid-30s, and looked about 28 (a little plump, feathery brown hair around a pretty, slightly time-ravaged face: a West Side Jeanne Moreau).

She wasn’t saying much — whether out of agreement or despair, I couldn’t tell — but from time to time she supplied political information in a simple, unself-conscious way, and when she did, everyone from George McGovern to Al Lowenstein stopped to listen. They seemed to respect her opinion, and, as one of the local Democrats explained to me, they all knew her background as an influence in New York campaigns for more than a decade, a former district leader, a near miss for the job of New York county leader once occupied by Carmine De Sapio, and one of the people Robert Kennedy had trusted most as both friend and adviser.

In fact, my informant went on, looking a little surprised, she was probably the political antenna Senator Kennedy trusted most in the state, and many important decisions (including the historic one to run in the Presidential primaries) were firmed up or altered during their conferences, which tradi- tionally took place rushing to or from the shuttle flights to Washington.

I understood the surprise. Robert Kennedy was not exactly a champion of Women’s Liberation; at least, not in any way except by contrast with Jack Kennedy, who couldn’t take women in politics seriously at all. And that, plus the obvious regard of leaders in the room, was surprise enough: neither of us stopped to wonder why Ronnie Eldridge remained undiscovered by the press; why, for instance, “Eldridge” wasn’t as familiar as “Lowenstein,” though Ronnie had helped to found the Dump Johnson movement, and the first meetings had been held in her living room. We just assumed that the press covered women politicians with reluctance, as if convinced that the real power couldn’t be there. “I don’t like to report on women in Congress,” a respected network analyst had once told me. “People make fun of them, and if I take them seriously, they make fun of me.”

Still, I had heard of her via the grapevine before that meeting. “She’s my political rabbi,” Jack Newfield used to say, and many of the younger activists in or near the Democratic Party seemed to go to her for quiet advice. Ron Moss, a lawyer and fellow district leader, called her “the mother of us all — she’s nurtured so much of the political reform movement that, whether they hate her or love her, they trust her information and seek out her advice.”

Since then, the grapevine has kept humming. Having become sufficiently disillusioned with clubhouse politics before Kennedy’s death to quit as district leader (she remembers mail addressed to “The Honorable Ronnie” and free passes to Yonkers Raceway as the outstanding features of that position), she was further along in her recognition of realignments in both parties — and, in New York, their continuing Balkanization — than those Democrats who still secretly hoped a Presidential victory might unify them. After Nixon’s victory, the New Democratic Coalition got under way, with Ronnie on its executive committee, but even the Coalition seemed too big and unwieldy to her — too much of an effort to string together a variety of dissenting groups. As an alternative structure to the Democratic Party and a pressure group on a wide variety of issues, it would end up, she was afraid, with the same middle-class people doing everything.

From ex-Kennedy aide Adam Walinsky to ex-McCarthy supporters, some of whom strongly disapprove of her (and defeated her for state committeewoman at the primary two weeks after Bobby’s death), there is agreement on her good instincts about elections, if not about the future of the NDC. “Somehow, Ronnie seemed to know even before Procaccino won the primary that we were all going to end up supporting Lindsay,” said one NDC leader. “She was more prepared to support a Republican than we were, since she’d already given up on conventional parties in the city anyway. When we had trouble getting an endorsement of Lindsay for a while after the primary, I think she got more impatient with the NDC than ever. She has no patience with deal-making. She thought we should just get down to work.

As Adam Walinsky admits, “Ronnie knew that Lindsay could win at a time when I wasn’t sure he had a chance.”

That early confidence endeared her to the Lindsay campaign staff, and she joined it as a liaison with Democrats who couldn’t stomach Procaccino. They occasionally criticized her for not being a properly neutral conduit of all Democratic views (“too hostile to certain reformers,” was one verdict); for voicing her personal views too strongly (with Bella Abzug, Women Strike for Peace organizer, she urged the introduction of Vietnam as a populist, taxpayers’ issue at a time when some aides winced at the word “peace”); or for being too agreeable with Lindsay’s campaign manager, Dick Aurelio. But the fact remained that her communications within the splintered Democratic Party were probably as good as anyone’s, and that she was one of the few people from whom Lindsay’s existing campaign staff could take advice without tempers blowing up.

I used to see her at the Fifth Avenue headquarters or some meeting of heavyweight Democratic contributors, always calm and always working with primary interest in getting something done and little apparent interest in what other people thought about her. She even got along well with aides like Jay Kriegel, whose combination of youth and confidence in his own intelligence often put people off. And she hit it off with the mayor himself, whom she hadn’t met until the campaign began, even though the popular wisdom was that he didn’t work well with women.

So it should have been no surprise when, after the election, she was given the job of special assistant to the mayor. (In fact, had she been a man and/or from a borough other than Manhattan, she might have been named the Democratic deputy mayor, at an equal level with Aurelio; there are some Eldrige-boosters around town who are upset that she was not. As it is, there may still be another deputy appointed, ideally a Jew from Brooklyn or Queens.) But reporters kept remarking on “a woman in City Hall” who will, like it or not, have considerable authority over political patronage (a far cry from Bess Myerson’s consumer post). And Ronnie herself seemed a little stunned.

“It isn’t that I don’t think I can do it,” she explained, trying to keep an enormous red dog named Samantha from climbing into her lap as we sat in the living room of her comfortable West 93rd Street cooperative. “The more you meet political leaders, the more you’re convinced it can’t be as difficult as you thought. It just seems strange to be inside an administration, getting paid; turning professional for the first time. I guess I’m losing my cover as a nice Jewish housewife.”

Though a psychoanalyst husband named Larry, two daughters aged 7 and 8, and a 10-year-old son were racketing around the kitchen at that very moment, it seemed unlikely that anybody else would support her self-image as Jewish housewife. As mayoral assistant she will have special responsibility for coordinating the 58-member Fusion Advisory Council, a potential hornet’s nest in itself. She will also deal with patronage problems, help decide who gets on what committee, and share some responsibility for communications with local and issue groups.

In fact, she hadn’t yet been told all her duties, but was already worrying about possible conflicts between working for the mayor and encouraging local groups that would and should be pressuring him. Her deepest belief was that parties were fading, and that a variety of issue groups ought to take their place. But could she encourage these issue groups while she was on a salary?

Couldn’t she consider her salary as coming from taxpayers, not the mayor? She thought about that for a moment and smiled. “Good,” she said. “It makes being on the inside seem less of a change, less shocking. Now, if I can just keep my housekeeper, and get up in time to make breakfast and get three kids off to school before those early City Hall meetings, everything will be all right.”

“Anyway,” she explained, “I was born political. I remember being 5 years old and wearing an FDR button, while my best girlfriend wore one for Landon. All my kids have grown up with buttons and placards on their baby carriages. I feel guilty about them, but their teachers say they’re doing fine. Emily writes letters to Nixon about the war, and worries about Black people who have to live in bad houses and don’t have air conditioning.” She smiled at the last, and added that her son once asked her why she didn’t run for President. “But he was really disappointed,” she said, “when he found out I wasn’t going to be mayor. He thinks we should all live at Gracie Mansion.”

As it was, calling up people for opinions of Ronnie Eldridge in City Hall, I found that several assumed I was asking about Ronnie as mayor. Ron Moss said yes, he’d been hoping to make her a candidate for years. Jack Newfield said he would back her. Steve Smith said yes indeed, she was his candidate. “I’m for her,” he said. “It’s some tragedy for the Democrats that they never recognized her potential, and now the Republicans have.” So the woman behind the scenes is now in City Hall, with a framed copy of a 1965 letter from Robert Kennedy on the wall. Scrawled across the bottom it says, “Why don’t you run for mayor?” The press had better pay more attention. Ronnie might be in City Hall to stay.