Editor’s note: This story first appeared in the December 20, 1971, issue of New York, which contained an insert launching Ms. Magazine. We are republishing a selection of Gloria Steinem’s writing from our archive to celebrate her 90th birthday.

A very, very long time ago (about three or four years), I took a certain secure and righteous pleasure in saying the things that women are supposed to say.

I remember with pain —

“My work won’t interfere with marriage. After all, I can always keep my typewriter at home.” Or:

“I don’t want to write about women’s stuff. I want to write about foreign policy.” Or:

“Black families were forced into matriarchy, so I see why black women have to step back and let their men get ahead.” Or:

“I know we’re helping Chicano groups that are tough on women, but that’s their culture.” Or:

“Who would want to join a women’s group? I’ve never been a joiner, have you?” Or (when bragging):

“He says I write about abstract ideas like a man.”

I suppose it’s obvious from the kinds of statements I chose that I was secretly non-confirming. (I wasn’t married. I was earning a living at a profession I cared about, and I had basically if quietly opted out of the “feminine” role.) But that made it all the more necessary to repeat some Conventional Wisdom, even to look as conventional as I could manage, if I was to avoid the punishments reserved by society for women who don’t do as society says. I therefore learned to Uncle Tom with subtlety, logic, and humor. Sometimes, I even believed it myself.

If it weren’t for the Women’s Movement, I might still be dissembling away. But the ideas of this great sea-change in women’s view of ourselves are contagious and irresistible. They hit women like a revelation, as if we had left a small dark room and walked into the sun.

At first my discoveries seemed complex and personal. In fact, they were the same ones so many millions of women have made and are making. Greatly simplified, they went like this: Women are human beings first, with minor differences from men that apply largely to the act of reproduction. We share the dreams, capabilities, and weaknesses of all human beings, but our occasional pregnancies and other visible differences have been used — even more pervasively, if less brutally, than racial differences have been used — to mark us for an elaborate division of labor that may once have been practical but has since become cruel and false. The division is continued for clear reason, consciously or not: the economic and social profit of men as a group.

Once feminist realization dawned, I reacted in what turned out to be predictable ways. First, I was amazed at the simplicity and obviousness of a realization that made sense, at last, of my life experience: I couldn’t figure out why I hadn’t seen it before. Second, I realized, painfully, how far that new vision of life was from the system around us, and how tough it would be to explain the feminist realization at all, much less to get people (especially, thought not only, men) to accept so drastic a change.

But I tried to explain. God knows (she knows) that women try. We make analogies with other groups that have been marked for subservient roles in order to assist blocked imaginations. We supply endless facts and statistics of injustice, reeling them off until we feel like human information-retrieval machines. We lean heavily on the device of reversal. (If there is a male reader to whom all my pre-realization statements seem perfectly logical, for instance, let him substitute “men” for “women” or himself for me in each sentence, and see how he feels. “My work won’t interfere with marriage …” “… Chicana groups that are tough on men …” You get the idea.)

We even use logic. If a woman spends a year bearing and nursing a child, for instance, she is supposed to have the primary responsibility for raising that child to adulthood. That’s logic by the male definition, but it often makes women feel children are their only function or discourages them from being mothers at all. Wouldn’t it be just as logical to say that the child has two parents, both equally responsible for child-rearing, and that therefore the father should compensate for the extra year by spending more than half of the time with the child? Now that’s logic.

Occasionally, these efforts at explaining succeed. More often, I get the feeling that we are speaking Urdu and the men are speaking Pali. As for logic, it’s in the eye of the logician.

Painful or not, both stages of reaction to our discovery have a great reward. They give birth to sisterhood.

First, we share with each other the exhilaration of growth and self-discovery, the sensation of having the scales fall from our eyes. Whether we are giving other women this new knowledge or receiving it from them, the pleasure for all concerned is enormous. And very moving.

In the second stage, when we’re exhausted from dredging up facts and arguments for the men whom we had previously thought advanced and intelligent, we make another simple discovery. Women understand. We may share experiences, make jokes, paint pictures, and describe humiliations that mean nothing to men, but women understand.

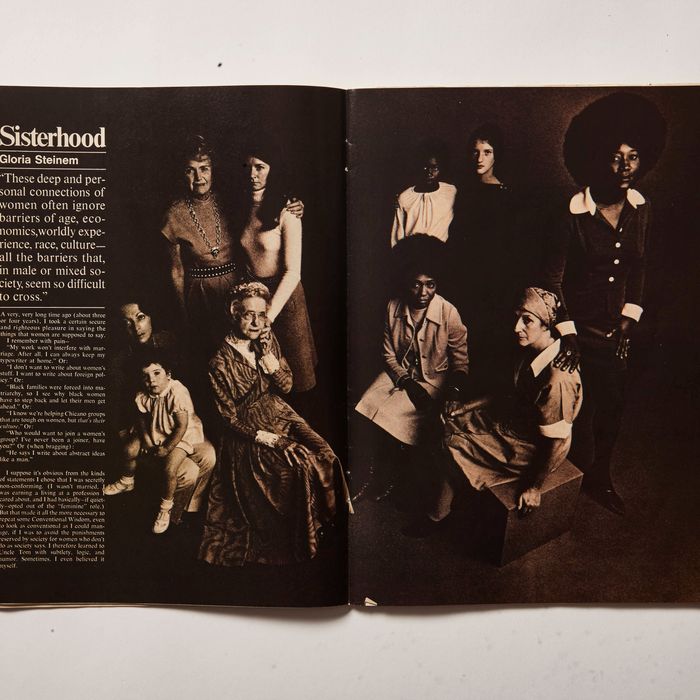

The odd thing about these deep and personal connections of women is that they often ignore barriers of age, economics, worldly experience, race, culture — all the barriers that, in male or mixed society, had seemed so difficult to cross.

I remember meeting with a group of women in Missouri who, because they had come in equal numbers from the small town and from its nearby campus, seemed to be split between wives white white gloves welded to their wrists and students with boots who talked about “imperialism” and “oppression.” Planning for a child care center had brought them together, but the meeting seemed hopeless until three of the booted young women began to argue among themselves about a young male professor, the leader of the radicals on campus, who accused all women unwilling to run mimeograph machines of not being sufficiently devoted to the case. As for child care centers, he felt their effect of allowing women to compete with men for jobs was part of the “feminization’ of the American male and American culture.

“He sounds just like my husband,” said one of the white-gloved women, “only he wants me to have bake-sales and collect door-to-door for his Republican Party.

The young women had sense enough to take it from there. What did boots or white gloves matter if they were all getting treated like servants and children? Before they broke up, they were discussing the myth of the vaginal orgasm and planning to meet every week. “Men think we’re whatever it is we do for men,” explained one of the housewives. “It’s only by getting together with other women that we’ll ever find out who we are.”

Even racial differences become a little less hopeless once we discover this mutuality of our life experience as women. At a meeting run by black women domestics who had formed a job cooperative in Alabama, a white housewife asked me about the consciousness-raising sessions or “rap groups” that are the basic unit of the Women’s Movement. I explained that while men, even minority men, usually had someplace where they could get together every day and be themselves, women were isolated in their houses; isolated from each other. We had no street corners, no bars, no offices, no territory that was recognized as ours. Rap groups were an effort to create that free place: an occasional chance for total honesty and support from our sisters.

As I talked about isolation, the feeling that there must be something wrong with us if we weren’t content to be housekeepers and mothers, tears began to stream down the cheeks of this dignified woman — clearly as much of a surprise to her as to us. For the black women, some barrier was broken down by seeing her cry.

“He does it to us both, honey,” said the black woman next to her, putting an arm around her shoulders. “If it’s your own kitchen or somebody else’s, you still don’t get treated like people. Women’s work just doesn’t count.”

The meeting ended with a housewife organizing a support group of white women who would extract from their husbands a living wage for domestic workers and help them fight the local hierarchy: a support group without which the domestic workers felt their small and brave cooperative could not survive.

As for the “matriarchal” argument that I swallowed in pre-feminist days, I now understand why many black women resent it and feel that it’s the white sociologist’s way of encouraging the black community to imitate a white suburban lifestyle. (“If I end up cooking grits for revolutionaries,” explained a black woman poet from Chicago, “it isn’t my revolution. Black men and women need to work together for partnership, not patriarchy. You can’t have liberation for half a race.”) In fact, some black women wonder if criticism of the strength they were forced to develop isn’t a way to keep half the black community working at lowered capacity and lowered pay, as well as to attribute some of black men’s sufferings to black women, instead of to their real source — white racism. I wonder with them.

Looking back at all those male-approved things I used to say, the basic hang-up seems clear: a lack of esteem for women — black women, Chicana women, white women — and for myself.

This is the most tragic punishment that society inflicts on any second-class group. Ultimately, the brainwashing works, and we ourselves come to believe our group is inferior. Even if we achieve a little success in the world and think of ourselves as “different,” we don’t want to associate with our group. We want to identify up, not down (clearly my problem in not wanting to write about women, and not wanting to join women’s groups). We want to be the only woman in the office, or the only black family on the block, or the only Jew in the club.

The pain of looking back at wasted, imitative years is enormous. Trying to write like men. Valuing myself and other women according to the degree of our acceptance by men — socially, in politics, and in our professions. It’s as painful as it is now to hear two grown-up female human beings competing with each other on the basis of their husbands’ status, like servants whose identity rests on the wealth or accomplishments of their employers.

And this lack of esteem that makes us put each other down is still the major enemy of sisterhood. Women who are conforming to society’s expectations view the non-conformists with justifiable alarm. “Those noisy, unfeminine women,” they say to themselves. “They will only make trouble for us all.” Women who are quietly non-conforming, hoping nobody else will notice, are even more alarmed because they too have more to lose. And that makes sense, too.

Because the status quo protects itself by punishing all challengers, especially women whose rebellion strikes at the most fundamental social organization: the sex roles that convince half the population its identity depends on being first in work or in war, and the other half that it must serve as docile (“feminine”) unpaid or underpaid labor. There seems to be no punishment inside the white male club that quite equals the ridicule and personal viciousness reserved for women who rebel. Attractive or young women who act forcefully are assumed to be male-controlled. If they succeed, it could only have been sexually, through men. Old women or women considered unattractive by male standards are accused of acting only out of bitterness, because they could not get a man. Any woman who chooses to behave like a full human being should be warned that the armies of the status quo will treat her as something of a dirty joke; that’s their natural and first weapon. She will need sisterhood.

All of that is meant to be a warning but not a discouragement. There are so many more rewards than punishments.

For myself, I can now admit anger, and use it constructively, where once I would have submerged it and let it fester into guilt or collect for some destructive explosion.

I have met brave women who are exploring the outer edge of human possibility, with no history to guide them, and with a courage to make themselves vulnerable that I find moving beyond the words to express it.

I no longer think that I do not exist, which was my version of that lack of self-esteem afflicting many women. (If male standards weren’t natural to me, and they were the only standards, how could I exist?) This means that I am less likely to need male values to identify myself with and am less vulnerable to classic arguments (“If you don’t like me, you’re not a Real Women” — said by a man who is Coming On. “If you don’t like me, you are not a Real Person, and you can’t relate to other people” — said by anyone who understands blackmail as an art).

I can sometimes deal with men as equals and therefore can afford to like them for the first time.

I have discovered politics that are not intellectual or superimposed. They are organic, because I finally understand why I for years inexplicably identified with “out” groups. I belong to one, too. It was take a coalition of such groups to achieve a society in which, at a minimum, no one is born into a second-class role because of visible difference, because of race or sex.

I no longer feel strange by myself, or with a group of women in public. I feel just fine.

I am continually moved to discover I have sisters.

I am beginning, just beginning, to find out who I am.