Editor’s note: This story first appeared in the November 10, 1969, issue of New York. We are republishing a selection of Gloria Steinem’s writing from our archive to celebrate her 90th birthday.

When the Peace Movement was still young, green, and paranoid, it tended to condemn American soldiers in Vietnam right along with the military and political leaders who sent them there. Somehow draftees were supposed to burn their cards; plead homosexuality; move to Canada; choose prison or the stockade. If, at the age of 18 or so, they failed to make any of these drastic and sophisticated choices, thus ending up with a good chance of getting maimed or killed in a far-off jungle, they were often thought to condone the war, or even to like it.

Now most of the Peace Movement is mature enough to spread the broad, compassionate umbrella of October’s moratorium, welcoming old enemies with a modicum of grace; our soldiers (with the exception of gung ho officers and some Green Berets) are more likely to be regarded as victims and potential allies. Near many of the big training bases in this country, for instance, there are coffee houses, run jointly by Movement students and ex-G.I.’s, where soldiers can go to discuss problems and get non-Establishment answers. Peace workers even cut their hair and dress “straight” to bridge the social gap between them and some of the redneck, blue-collar G.I.’s. (On Moratorium Day in Boston, a Kentucky G.I. sought out a Boston University student he had beaten up last year after a peace demonstration, apologized, and asked for a black armband so he could join the march.) The activists understand how difficult it is for returned soldiers, who probably have been wounded or seen buddies killed, to question the cause for which the blood was spilled. And, regardless of position on the war, the activists agitate for G.I. civil rights, the publication of uncensored G.I. newspapers, and the like — an issue that is growing into as big a storm center as the draft.

Unfortunately, a lot of this reaching-out came too late. “Our boys in Vietnam” had already become a jingoistic symbol, whether the boys themselves liked it or not. (To be fair, they might have opted for being symbols anyway, because of divisions in style and class. As a Marine sergeant explained at the Pentagon march, “I agree with a whole lot they say, but I’m damned if I’ll admit it to these hippie college-boy bums.”) The result is that the more image-conscious doves are still reluctant to be seen with, or try for any coalition with, “our boys”; and many Vietnam veterans come home disillusioned and physically disabled only to find that they are treated like war-lovers, or roundly ignored.

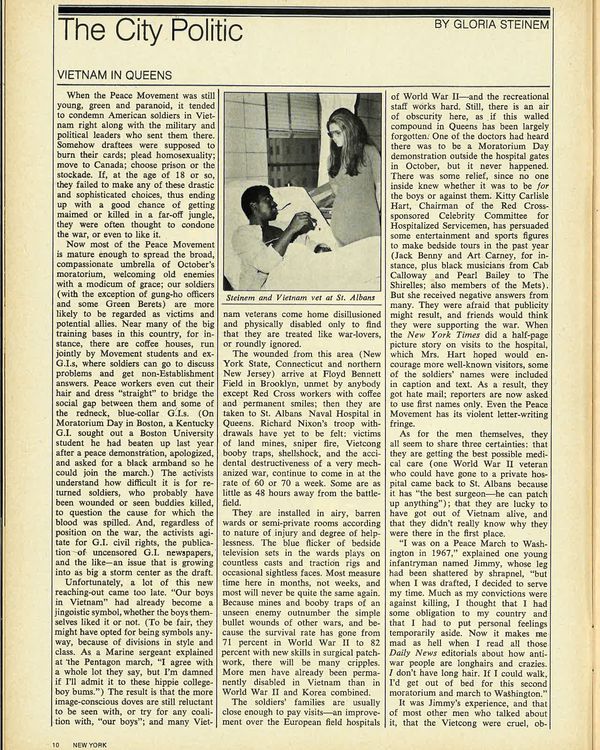

The wounded from this area (New York State, Connecticut, and northern New Jersey) arrive at Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn, unmet by anybody except Red Cross workers with coffee and permanent smiles; then they are taken to St. Albans Naval Hospital in Queens.

Richard Nixon’s troop withdrawals have yet to be felt: victims of land mines, sniper fire, Vietcong booby traps, shell shock, and the accidental destructiveness of a very mechanized war, continue to come in at the rate of 60 or 70 a week. Some are as little as 48 hours away from the battlefield.

They are installed in airy, barren wards or semi-private rooms according to nature of injury and degree of helplessness. The blue flicker of bedside television sets in the wards plays on countless casts and traction rigs and occasional sightless faces. Most measure time here in months, not weeks, and most will never be quite the same again. Because mines and booby traps of an unseen enemy outnumber the simple bullet wounds of other wars, and because the survival rate has gone from 71 percent in World War II to 82 percent with new skills in surgical patchwork, there will be many cripples. More men have already been permanently disabled in Vietnam than in World War II and Korea combined.

The soldiers’ families are usually close enough to pay visits — an improvement over the European field hospitals of World War II — and the recreational staff works hard. Still, there is an air of obscurity here, as if this walled compound in Queens has been largely forgotten. One of the doctors had heard there was to be a Moratorium Day demonstration outside the hospital gates in October, but it never happened. There was some relief, since no one inside knew whether it was to be for the boys or against them. Kitty Carlisle Hart, chairman of the Red Cross–sponsored Celebrity Committee for Hospitalized Servicemen, has persuaded some entertainment and sports figures to make bedside tours in the past year (Jack Benny and Art Carney, for instance, plus Black musicians from Cab Calloway and Pearl Bailey to the Shirelles; also members of the Mets). But she received negative answers from many. They were afraid that publicity might result, and friends would think they were supporting the war. When the New York Times did a half-page picture story on visits to the hospital, which Mrs. Hart hoped would encourage more well-known visitors, some of the soldiers’ names were included in caption and text. As a result, they got hate mail; reporters are now asked to use first names only. Even the Peace Movement has its violent letter-writing fringe.

As for the men themselves, they all seem to share three certainties: that they are getting the best possible medical care (one World War II veteran who could have gone to a private hospital came back to St. Albans because it has “the best surgeon — he can patch up anything”); that they are lucky to have got out of Vietnam alive, and that they didn’t really know why they were there in the first place.

“I was on a Peace March to Washington in 1967,” explained one young infantryman named Jimmy, whose leg had been shattered by shrapnel, “but when I was drafted, I decided to serve my time. Much as my convictions were against killing, I thought that I had some obligation to my country and that I had to put personal feelings temporarily aside. Now it makes me mad as hell when I read all those Daily News editorials about how antiwar people are longhairs and crazies. I don’t have long hair. If I could walk, I’d get out of bed for this second moratorium and march to Washington.”

It was Jimmy’s experience, and that of most other men who talked about it, that the Vietcong were cruel, obsessed, and infinitely more given to atrocities than American soldiers. (“Those kids who wave the Vietcong flag around get me mad, too,” Jimmy said. “They just don’t know what they’re doing.”) But he felt we had no right or ability to permanently protect Vietnamese from each other. “I write to my buddies who are still over there,” he said. “Our guys and the ARVN sell American machine guns and grenades on the black market. The VC buy them, and a week later we’re blown up by our own stuff. It’s crazy. We should get out.”

A 19-year-old with bad teeth and many tattoos said he hoped American tourists would go to Vietnam, that they should be told it was a vacation spot. Then he cackled darkly, as if imagining a soft white tourist in the jungle. He hated Humphrey and Nixon, he said, and thought Bobby Kennedy or even Goldwater would have made a better President because they were “more like real men — they would have got us out.”

Of the 40-some men I talked to in two wards, five felt we should keep on fighting. A handsome boy with a guitar said, “We could beat those bastards if they let us fight the way we wanted to. We see them, and some officer says, ‘Don’t fire on them till they fire on you.’ If we leave, Vietnam will go Communist, and all those other countries too.” He and his friend agreed that leaving now would mean admitting that 40,000 American lives had been wasted.

“You see that man over there?” asked one soldier with a plastic-coated leg elaborately suspended. He gestured toward a blond boy who was groaning as three orderlies removed a cast, revealing a large steel bolt protruding bloodily from both sides of his knee. “I could write a book. I mean, you see these guys suffering, and you wonder, ‘What the hell for?’”

“We’ve got a whole world here,” said a one-time assistant manager at the Village Gate. “We sit on each other’s beds and talk about what the surgeon said today like a bunch of old ladies discussing their operations. But every once in a while, we wonder if anybody knows that we’re here.”

The Peace Movement’s welcoming of soldiers could be a tactic. As Tom Hayden said before Chicago, you can’t radicalize the individual cop if you’re going to lump them all together as pigs. Or it could be a philosophy that stretches to include even the political hawks and the generals. “We want to protect the victim from being the victim,” said Cesar Chavez, speaking his feelings about domestic injustice as well as Vietnam. “We want to protect the executioner from being the executioner.”