It’s almost unimaginable now that Suzanne Scanlon, who’s an English professor in Chicago and the author of two novels, spent three years of her early 20s in a state mental institution. As a Barnard student, she’d attempted suicide, suffering from a depression that stemmed from her unresolved grief over the death of her mother when Scanlon was only 8 years old. But instead of being treated and released, she was transferred from the care of one incompetent doctor to another for years, given shifting diagnoses and experimental drug treatments, and locked away from the world for so long that reentering it began to seem impossible.

Yet, as Scanlon writes in her new memoir Committed: On Meaning and Madwomen, the experience was in some ways perversely, almost inadvertently, helpful. “In the hospital I took it for granted, the idea that we somehow needed to get worse,” she says. “They would break us apart and then put us back together again.” This process of breaking apart shaped Scanlon’s life and worldview irreparably. In her novels Promising Young Women and Her 37th Year: An Index, Scanlon used the same material that she then went on to mine in her memoir, but this book reads very differently — it seamlessly interweaves the writing of other writers and thinkers in a conversational way, sort of like if Maggie Nelson didn’t write like an academic. Scanlon says that she sees the novels and the memoir as one ongoing book, with a story that changes as she gets older and is able to see things from a distance. The result is a deep, sometimes harrowing book about loss, grief, and the way literary representations of mental illness shaped Scanlon’s experience of her own life.

Most people don’t have the experience you had anymore, unless they’re very rich, of being institutionalized for three years. What did you especially want to get down on the page about that experience?

For many years, I was trying to get out of what that situation did to me. But now, from my vantage as a mother and an educator, I see young people having very different experiences with mental-health care — just an ability to talk about it. And maybe the stigma is still very real, but also there may be less shame around it than I experienced. That was, in many ways, the most difficult thing about it for many years — that shame.

And I still have a hard time with that, and it’s part of what makes this book scary. Even though I’ve written about it before, there’s still something very fragile about returning to the material. It was such a specific moment in mental-health care that is now gone. Some of the ideas about what was helpful or necessary have definitely changed. The idea that someone should be in a hospital that long is now very clearly seen as a bad idea for lots of reasons. As I wrote about it, I came to see that I was also discovering how much it shaped my self. It wasn’t something where I could completely say, “Oh, this was bad,” because it was so much a part of me. In many ways, I think it was very helpful. I can’t categorically say, “Oh, that was this awful treatment that I had to recover from.” This question I talked with Sarah Schulman a lot about was, “How much did this help you? And are you here now writing this because it was fundamentally very helpful and in many ways saved you?” And I couldn’t say no to that anymore. When I started the book, maybe I wanted to say no to that.

So that was part of the question of the book. And because I see how shitty mental-health care is now. There are things about the attention I got and the kind of help I got that people don’t get today that led me to be this person who could survive in the world. A lot of people don’t get that. I also wanted to acknowledge the complexity of the experience. And maybe in Promising Young Women, it was more negative to me and it was more absurd, I think. But that book was also more speculative because I didn’t have the answer. So I was playing it out in characters, different ways of living within this experience.

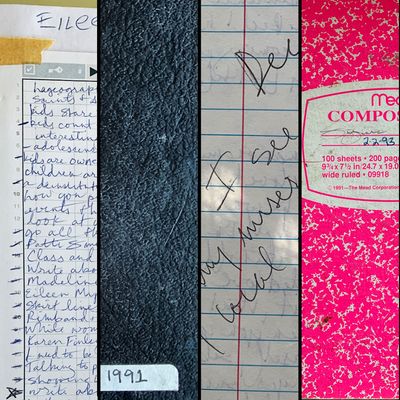

You had your medical records to go off of, as well as your own notebooks, and you talked a little bit in the book about how you had resisted at first opening up those notebooks. But then they ended up being so helpful to you in writing this book.

I really saw myself almost as a mother now to this girl. And I see how messed up, how confused and lost and suffering she was in a way that I can’t relate to anymore. I mean, it’s not that I don’t write anymore about things that are plaguing me and painful. But it was a different kind of writing — it was much more hopeless and desperate. Now I think more about an audience. Back then, I didn’t know who the audience was. This real desire for an audience was in the writing itself, and not just the desire for an audience, but the desire to be a person and to communicate.

Describe a little bit what the treatment was like in the hospital.

There were always new drugs, and it was a collective thing. Everybody’s going off whatever we were all taking, and now we’re all taking Ativan or whatever it was. And then it was suddenly like, nobody can take Ativan anymore. It was suddenly like they discovered that it wasn’t good, or it had bad side effects, so we all had to go off it and then do another.

So we were often processing this, adjusting to drugs constantly or dealing with side effects. It’s very hard to separate what was wrong with us or what we were suffering with from that heavy pharmaceutical treatment. And there were always new drugs.

In your notebook, you wrote down a line that one of the doctors said that you felt was a key insight for you, that actually helped you.

He said, “Being sick is a cure for how bad you feel.” At that point, I had been there so long and I was determined to be sick or to still be sick or to not get better. And I think it’s very hard. Even the idea of getting better was so disturbing to me when I still felt so awful. But what they mean about getting better is not that you’re not going to feel awful, but it’s more about getting better at dealing with life and coping with these emotions and so on. It was very much like this idea of radical acceptance, like you’re still going to feel horrible, but oddly, that’s such a paradigm shift. So much of the problem in the hospital was this idea that you’re sick and you get better. It was quite binary. In order to keep getting this care that was inherent in the hospital, it was like you had to be sick or better, but ultimately being better was this new way of being abandoned. And you didn’t have tools, or you’d lost the tools if you ever had them, to live on your own. They weren’t preparing us for coping with life.

And yet you managed to leave. Can you describe a little bit what your first days and weeks and months outside of the hospital were like and what you were up to at that time in your life and your decision to live?This was very hard to write about because I definitely was worse when I left, and it took a long time to get better. And I was hospitalized again a number of times, and I was continually struggling with suicidal ideation, as we call it now. I went back to school. I think I was lucky to still be able to do that eventually. And so I think I had another year and a half or so of college. It was September 1996, the last time I was hospitalized. That was when I had to decide that being hospitalized was a dead end and that continuing in this pattern with doctors was a dead end.

I was able to make this internal decision to stop letting myself think about suicide as an option. And I absolutely wasn’t able to say any of this at the time because I didn’t really believe it. It’s only many, many years later, looking at what happened, that I see that that was very important. It was like quitting a drug. That was about the same time I had started Nardil. So as much as I want to attribute it to this powerful moment of personal agency, I also, in writing the book, see that Nardil probably really, really helped me. It was the only antidepressant I ever remember helping me. It changed my life.

I think I really believed when I was in the hospital that if we found the right drug, that would be it. And I’ve stopped believing in that. And yet also, I still need them on some level.

So you initially went to the hospital because you tried to commit suicide. And then you were there for years, and one of the things that struck me about that was during my comparatively very brief time in the hospital, only a little less than a month, the people who got out the fastest were the people who were there because of suicide attempts.

Really?

There was a girl who tried to drive her car off the Williamsburg Bridge, and she was only there for four or five days. I think they just talk to you and make sure that you have family support or some external support, and they make follow-up appointments with you, and they put you on whatever antidepressant they’re going to put you on. And then they just are like, “Well, there’s nothing else we can really do here for this, so see you later,” basically. “Maybe call 911 if you feel like you’re going to drive your car off the Williamsburg Bridge again.” But I guess they know what they’re doing now more than they did then, at least.

I don’t know, I wouldn’t say that. I would say that it’s much more about money and insurance and decisions and the availability of care for people. I think a lot of it is people who repeatedly have these short-term stays. I mean, in the first short-term hospital, I saw plenty of that. And even then, we knew it was about insurance. It was when their insurance ran out. It’s not good.

In the book, you write against the idea that you are your diagnosis.

That’s how I see it now, obviously. I think again, still, the stigma is self-protective. The shame and the person I was back then who felt quite hopeless, for whom this idea of being sick was totalizing. Now, because I’m functioning in the world, I’m able to see that differently.

What about the books that you lived in and that shaped you and that you bring into this book so gracefully? You write a lot about Virginia Woolf and also about the Charlotte Perkins Gilman story “The Yellow Wallpaper,” and the way you initially read those things and the way that you read them later in life, especially as you were teaching them.

“The Yellow Wallpaper,” I didn’t love. When I first read it, it didn’t speak to me the way a book like The Lover or Beloved or these other books did when I was young, like 18, 19, 20. And it is funny because “The Yellow Wallpaper” could have been so obviously linked to my experience, but I wasn’t willing to read it that way. And so I reread it as part of this anthology, and there were these critical essays around control and discipline, and that became very interesting to me and made me want to revisit it, and that helped me. It so clearly seemed to be explaining or speaking to my own experience by that point in my life, and I was very much in a different life. My son was a baby.

Then I became fascinated with it. In revisiting it for this book, I became very interested in this alternate reading of it, now, because it became reclaimed as this feminist text and taught so much; students and readers in general have this one reading of it: The patriarchy made her crazy. But I’m also interested in her desire to ask for help.

I did really want to put my trust in doctors. In the hospital, there was this whole theory around this place where I was and the treatment plan there. And I write about this one woman who was very critical about it, and she didn’t stay long. They wanted her to give up AA meetings that she was going to, and to give up other outside responsibilities. So she saw through it in some ways. I think there has to be this desperation or belief in the idea that somebody will have this answer for you when, really, you’re the only one who can figure it out. But for me part of being young was wanting to be defined by someone else, as I wanted my mom to define me, so I would look for someone else to tell me who I was. But I’m not saying I was conscious of that or had control over it.

One way that a diagnosis can be helpful, though, is that it connects you to other people, and if there is a literature of your particular diagnosis, then you can read that specific literature and find little reflections of your experience in it.

This book must have been very difficult to write, I think, and one of the most difficult aspects of it, I am just guessing, is going back repeatedly to the circumstances of your mother’s death and the unresolved grief that you felt. And then your father’s very quick remarriage in the addition of the stepmother and her children, and then a year later the addition of their child to your family, and what that did to you as an 8- and 9-year-old kid and how that shaped your life. It’s hard to even extricate it from your experience of being institutionalized because it’s the big precursor to it.

That’s the hardest part for me to have to deal with coming out into the world. It feels so fragile. But I love writing and I love when something’s working; that’s the best feeling. It still can cause this emotional reaction in me because this is a thing that never heals. It’s just this part of me, and even still, I am surprised by it.

The stuff with my mom feels the most necessary to write, but it’s the most painful because it’s everything. Because my life would’ve been completely different had it not happened that way. It’s not that I feel like, Oh, I wish it hadn’t happened, because that doesn’t make any sense to who I am now. But I felt like for this book, I had to be more honest about her death as context for what happened after. I had an early reader who made that point, like, “You can’t leave out what happened in between your mom dying and you being hospitalized, because it’s not that many years.” That part was really hard to write, and it’s not going to make people in my family happy to read it, but the book needed it.

In the U.S., the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255.