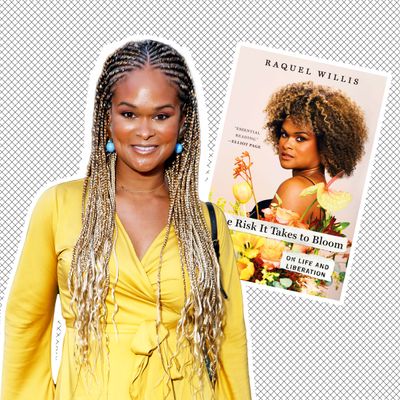

In 2014, Raquel Willis was still working at one of her first journalism jobs out of college. None of her colleagues knew she was trans. But when Willis heard about the suicide of 17-year-old trans girl Leelah Alcorn, she knew she had to say something. She recorded an emotional video pleading for more attention to be paid to the struggles of trans people. It immediately went viral, and she decided to come out as trans both publicly and to her colleagues. “You taught me that I am obligated to others, my community, and younger trans folks to blaze a path,” she writes in a letter addressed to Alcorn in her new memoir, The Risk It Takes to Bloom. It was a pivotal moment in a career that has married activism and journalism, propelling Willis from reporting for a small local paper in Georgia to becoming a national organizer for the Transgender Law Center and the executive editor of Out magazine.

In her memoir, Willis is honest and brave when writing about both her accolades and her shortcomings. She is quick to acknowledge when her desire for safety has clashed with her values as a queer activist — passages she easily could have withheld from the reader but thankfully doesn’t. She embraces the complications of surviving as a trans person. Even in moments of terror, as on a date gone horribly wrong, she maintains a powerful commitment to empathy.

Later this year, Willis will launch a podcast called Afterlives. Its first season will focus on the life and early death of Layleen Polanco, a 27-year-old trans woman who died in solitary confinement at Rikers Island in 2019. “The unfortunate truth is that death is such a feature in the lives of Black people, of trans people, of folks on the margins,” Willis told me, but she refuses to let tragedy impede her activism. “We have a duty to let those moments encourage us to grow and to bloom again and again.”

One of the things I most admire about this book is the generosity you show to people in your life and to yourself. I was struck by the chapter where you come out as gay to your mom. Against her advice, you then come out to your dad, who responds with rage and contempt. “Both of my parents were highly educated people who should know better,” you write, surprised by their reaction. But you also empathize with your family. What was it like returning to those moments of complexity in the memoir?

In an earlier draft, I was kind of matter-of-factly regurgitating the story I have been telling myself about that coming-out experience. And that’s often how it is, I think, for queer and trans folks and nonbinary folks. We have to tell our story so much that we often get our stories down to talking points. So I can nod to, I was raised in the South. That gives people a lot of information. I can say, I was raised Catholic. That gives people a lot of information. I think, of course, since I’m a Black woman, people make a lot of assumptions there as well. As I started to get into revisions, I got a new therapist, and that experience paralleled with trying to dig deeper into what that experience of coming out was like for me so young. It really added an element of healing I didn’t know I needed. That kind of starts my understanding of where this memoir is going in terms of reckoning with expectations.

Some of the most powerful sections in the book are the letters you write to the recently deceased. Many are to young trans people of color who were murdered by strangers or lovers or while incarcerated. You also include a letter to your father written after his death. What was your aim in using letters to address important figures in your life?

I drew inspiration from James Baldwin, the letter to his nephew, and Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me. I saw the epistolary form as a chance to break out of my journey as it was happening. The letters give me permission to speak directly to figures who changed the trajectory of my life’s purpose. I’m also able to shatter the wall with the reader. But what was important, of course, was making sure the narrative still moved forward. And these moments did actually happen in my life story organically. My father’s death coincided with me coming into my identity as a woman. Leelah Alcorn’s death was a catalyst for me to reconsider how important it was for me to be stealth in my career, versus using my career, my access, to make things easier for the next Leelahs out there.

I love how honestly you write about the experience of learning to date as a trans person — both its excitement and its moments of terror — from falling in love with Alessio in college to your frightening encounter with a cis man named Damon who grills you about your gender when you go to his house. What made you want to write about the full range of experiences you’ve faced?

There hasn’t been space to talk about how dating and seeking romance are a risk for trans people. Also, we have the agency to decide, Is the risk worth it?

Particularly for Black trans women, our lives can be at stake simply from flirtation. For instance, the experience of Islan Nettles, who I mention in the book, being catcalled on the street and then being murdered, essentially brutally attacked in a way that led to her murder.

It felt important not to feel like I had to share a fairy-tale experience with love. I haven’t had that experience. Most of the Black trans women — and Black women — I know have not had fairy-tale experiences. Folks are interested in messy or complicated relationships. I was excited to share my early experiences with romance because I don’t think we often hear enough about T4T experiences. And in some of my relationships then, there was also the interracial element that at points presented itself as more of a quagmire than us putting our gender-dysphoria baggage right beside each other.

The chapter on Damon was an exercise in trying to make sense of where I fell in the middle of hookup culture almost a decade ago, when there really wasn’t the same level of visibility. With the later chapter “Girls Night Outing,” there was a conversation I wanted to have about being a Black trans woman living in the era of Me Too. While we’re visible in some ways, those nuances of our experiences with misogyny are erased from dominant conversations.

About Blake Brockington, the 18-year-old transmasculine activist who died by suicide in 2015, you write, “Blake’s death revealed to me how visibility doesn’t necessarily lead to increased vitality for trans people.” How have your feelings about visibility changed during your time as an activist?

My relationship with visibility has become more complicated. In the time of the deaths of Leelah Alcorn and Blake Brockington and the emergence of Caitlyn Jenner, representation for representation’s sake was still the dominant frame. It was the end of the Obama era. Something that revealed itself during the Trump era is that identity isn’t enough. We see that right now with conservative politicians — in Tim Scott, a Black man running for office, or Vivek Ramaswamy and Nikki Haley. These figures make clear that identity isn’t enough. The values piece does matter. And then, of course, Caitlyn Jenner has shown her entire ass. Just because she is transgender doesn’t mean she’s invested in trans liberation. It’s become more complicated because now we have more case studies of the pitfalls of relying on identity as a signifier of progress.

But there is utility in visibility if we understand that it must be connected to changing the material realities of the most marginalized in our community. Are you using your visibility to speak on the genocide of Palestinians and the continued epidemic of violence against trans women of color and anti-Black police brutality and the failures of the United States to preserve our reproductive justice? If you’re not, then what is your visibility for other than your personal quest for validation?

During your first journalism job, as a reporter for the Monroe Chronicle, you decided to go stealth and not come out to your colleagues as trans. This leads to countless reckonings with your personal values. For instance, when considering whether to invite your partner, a gender-nonconforming woman, to a drag show you’re reviewing for work, you ask, “How strong were my values if a part of me desires the safety of being in a perceived cis, straight couple? What was the line? How far could I ethically go to keep my life sectioned off like this?” How did you decide to explore this in your memoir?

All figures are put on a pedestal, definitely folks who emerge as activists. There’s this idea that our politics are pure, that we always have the right thing to say, that we’re the most radical and progressive. And that’s not true. I have so many insecurities to work through — I’ve tried to work through many of them on the page. But I also have privileges that act as shields, that I have to consistently maneuver around to get to truth.

It was important to own that as a trans woman who was living with the choice not to share my transness with the world and fully living in my queerness; I had to make conscious decisions about that. I say that as someone who knows trans folks who don’t carry their identities on their sleeve or don’t want the weight of being visible in their everyday lives.

You open the memoir at the 2017 Women’s March, a moment full of highs and lows. You are asked to deliver a speech to the crowd, but the organizers cut you off before you can finish. The book concludes, however, at a genuine high point, with the success of the March for Black Trans Lives, where you deliver the speech one might wish you were able to give at the Women’s March. What stands out about the differences between those two events?

Perhaps the difference between my presence at the Women’s March and my presence at the March for Black Trans Lives in Brooklyn in 2020 is uncertainty and certainty. I feel like I recovered a sense of resolve that I had at 14, when I was coming out to my mom and had no idea what the reaction would be. Or when I came out as trans around age 20 with no idea what the reaction would be. Or when I decided to be open in my career as a trans woman after the death of Leelah Alcorn in 2014. There was a certainty that I had power and that the various groups of folks I belong to had power despite the powerlessness we felt in the moment — collectively, whether it was due to the pandemic or it was the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd and so many others.

You acknowledge how important it was for you to read other trans writers during your transition as a counterpoint to the shallow depictions of trans people many of us grew up seeing on TV. How do you see your memoir fitting alongside the books and blogs that were so vital to you when you were younger?

I hope The Risk It Takes to Bloom serves as a testament to the importance of southern voices in the discussion of trans liberation. I hope it encourages other folks to have an agenda around collective liberation. I’m very aware that it is unique in the sense of coming from a Black trans woman who had a certain amount of success and a career in journalism. I hope folks understand that trans folks aren’t waiting to be saved; we’re doing the work to elevate ourselves. I know that it’s just a bridge between what has come before — as recently as Geena Rocero’s Horse Barbie or Elliot Page’s Pageboy or Schuyler Bailar’s He/She/They — to whatever comes next. It’s just the bridge. And that’s also only talking about nonfiction. So we have folks like you and so many others holding up the fiction space.

Beyond the trans-canon discussion, I hope that whatever “general audience” means, the folks who fall into that category will be inspired to shatter their own expectations. We’re all trying to figure out how to navigate our time on this planet in pursuit of the truest form of self-expression and connection. You’re not going to get there unless you realize these systems of oppression were formed against all of us, even the people who think they have the most power.