When Ludovic de Saint Sernin, a young French designer, slid into her DMs, Jenna Lyons agreed immediately to meet him for breakfast while he was in New York. Saint Sernin is a darling of the international fashion press with a long Brâncusi face, shoulder-length waves, and a design philosophy that could fairly be called “empowered slut.” (His breakout piece was a grommeted pair of men’s underpants that lace up like a corset.) Five years before, he might have been reaching out to her peer to peer: She had spent 27 years designing J.Crew, where she revitalized a former mall brand and brought it all the way to the Met Gala. But no, it turned out, that wasn’t it. “When I started watching the show, I was like, Oh, I recognize her from something, but I didn’t know then,” he says. What drove his interest was not her long career in fashion but her current, more surprising one: as a new Real Housewife of New York City.

Saint Sernin is a “reality baby” (his words). He streams all of the Real Housewives series, from Auckland to Potomac, which he pronounces Pôtomac. (“I love the way you say Potomac,” Lyons says. “Makes it sound sexy.”) Lyons’s first season, the New York edition’s 14th, had premiered exactly one month before, and here at Sant Ambroeus, the little slice of Milan on Lafayette where the fashion industry gathers for $14 coconut yogurts, he’s aglow with interest. “I wanna know everything,” he tells her. “You know, I’m obsessed with Housewives.”

“I mean, listen,” Lyons says. “It was a massive, massive risk.”

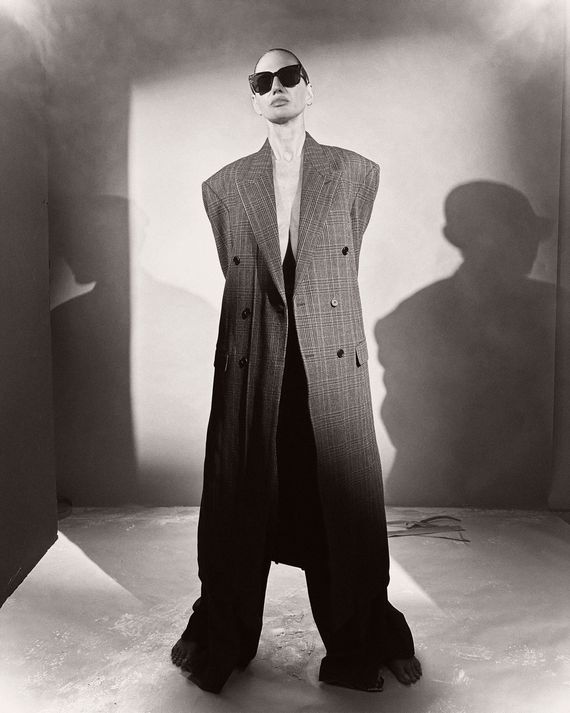

As if conveying the seriousness of the risk, she peers intently through her oversize glasses — one of her now-recognizable signatures from the show. (Other Lyonsisms include her syncopated patter and her retreat into a baby voice when confronted with conflict.) Viewers will also recognize the peacock-prep style she popularized at J.Crew, a mix of masculine and feminine, sex appeal and tomboyism, a mannish tailored shirt unbuttoned to the sternum. Today, it’s a well-loved marled sweatshirt from El Cosmico in Marfa with a strand of diamonds. She doesn’t immediately telegraph reality star, unless you happen to notice that her overflowing handbag is a Birkin. But that’s the point producers made by casting her. Lyons had been one of the biggest designers in America, and after her J.Crew exit, many expected her to jump to another American megabrand, a Coach or a Kate Spade or a Ralph Lauren. Even, a few speculated, to one of Paris’s vacant houses. “I was waiting to see what she was going to do,” Todd Snyder, who had run J.Crew’s men’s collections for many of the years Lyons ran the women’s, told me. “I remember saying, ‘If there’s anybody that could do their own collections …’ She just told me she wanted to do something different in her life.”

“I have a really different idea of what success looks like now,” Lyons says. Without the security of a single employer, she became a consultant-polymath, hustling to maintain. “The scaffolding that is required to build a life here is massive,” she tells me. “I think everyone’s scared of not having security. And I was terrified.” She lined up backroom corporate gigs consulting for a venture-capital firm she contractually can’t name and for Rockefeller Center on its retail strategy. Having fallen in love with interiors during her years working on J.Crew stores — and on her own previous home, whose Domino cover shoot has been Pinterested in perpetuity — she edged deeper into design, advising friends on their house and cottage projects.

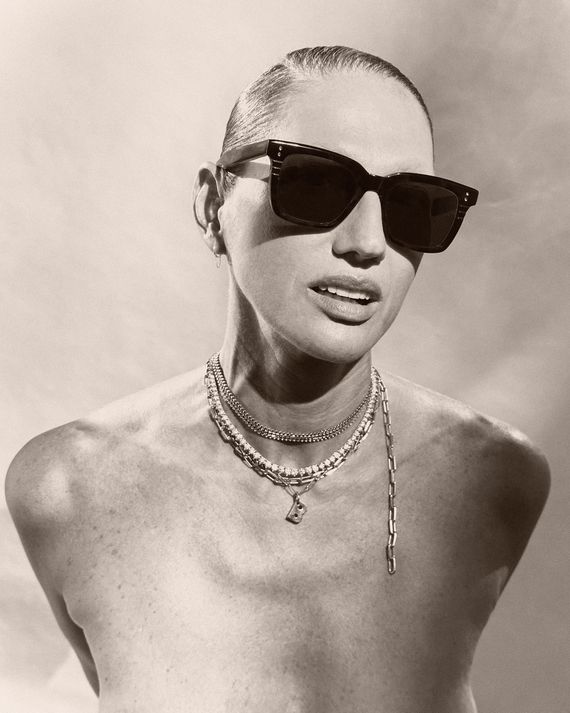

She could have receded into a comfortable, well-compensated anonymity. But she didn’t. Having tasted public-persona-hood at J.Crew, she continued to seek it out, and though wary about running toward fame, she also, clearly, ran toward it. Yet without a national brand behind her, Lyons’s most public-facing ventures seemed to founder. Stylish With Jenna Lyons, her 2020 television series that originally ran on what was then HBO Max, received mixed reviews and disappeared from streaming services altogether in the Warner Bros.–Discovery merger of 2022. A new company, LoveSeen, a line of false eyelashes — which Lyons wears owing to a genetic disorder, incontinentia pigmenti, that has left her without eyebrows or lashes of her own — went into 1,000 Target stores, but at many of them the lashes sat on the shelves. Target executives fretted. “They kept saying, ‘You need a national campaign for awareness,’” Lyons says, but she couldn’t afford one. “And then this comes in.”

“This” was RHONY, the beloved, reviled, and now rebooted Bravo reality series on which Lyons agreed to star. It is a delicate moment for the show, whose existing cast was replaced wholesale following a few years of declining ratings and last season’s allegations of racism among the wives. When news of Lyons’s casting came in May — hers had been the last contract signed, still unfinished as of the night before the announcement — the hometown response was befuddlement. As the New York Times headline put it, “The Famously Stylish Former President of J.Crew Has Joined the Rebooted ‘Real Housewives of New York City.’ Why?” “She and I had a long talk very late in the casting process, where I troubleshot every bad thing that could come about from this because I felt a little personally on the hook for this one,” says Andy Cohen, the Bravo exec turned ringleader of the Housewives universe. Lyons knew some of the past New York Housewives, like Carole Radziwill and Kelly Killoren Bensimon, socially, and “obviously I know all of them have suffered in their reputation,” she says.

Her motivation was her business. Not so much for the cash — careful not to nibble the hands that feed her, Lyons would say only, “It’s not an embarrassment of riches” — but the marketing opportunity is nearly priceless. For all the bad rap old-fashioned linear TV gets, Brett Bouttier, one of Lyons’s business partners, tells me it still moves the needle on product sales. “It’s directly related,” he says. “You can see it in the numbers practically instantly. I can watch it move by time zone.”

Many Housewives try, but few become Skinnygirls like Bethenny Frankel, the rags-to-richest Housewife who has been the most successful so far at selling herself and her products with the show as her springboard. (Her line, begun with diet margaritas, has expanded to include salad dressings, preserves, and, briefly, deli meats.) More stumble — Sonja Morgan and her designer toaster come to mind — by trying to hawk products only to find that they are the product themselves.

So Lyons struck the reality-TV bargain: to sacrifice control and risk tabloid-style humiliation for attention and possible gain. In so doing, she’s not only inviting a level of public scrutiny she hasn’t had since her J.Crew days but also testing the limits of niche fame. In New York, Jenna Lyons is a notable. Across America, on televisions and streamers, she’s a question mark. “This is one of the New York Housewives, right, the fashion girl?” says Chelsey Stephens, a casting director who has worked on several Housewives cities, when I ask about Lyons. “She might be big within the fashion world, but is she big kind of across the scale?”

Will the true Housewives devotees, the ones who listen to Housewives podcasts and attend BravoCon and know what went down in the Beauty Lab + Laser parking lot, take to Lyons’s particular, and maybe peculiar, brand of wonky chic? If Lyons is an unusual choice for the series — among other things, she’s an out queer woman — there is the real possibility that she’s actually not unusual enough. She doesn’t emote. She is empathic to an almost disquieting degree, and to sit with her is to experience a level of interest that can border on interrogation. These are not the qualities that generally distinguish Housewives. She doesn’t even drink. Her most salient qualification, the most Housewife-ish thing about her, may be her openness to rolling the dice on it at all. “She says ‘yes,’” her friend Charles Porch, a top executive at Instagram, tells me, “to everything and anything.”

Lyons is the first to admit she had barely seen the show before joining the cast. The idea came, she has said, from a suggestion made by the hosts of a podcast she was a guest on, Dyking Out. She is not a reality baby like Saint Sernin; she seems curious why anyone would be.

“What do you love about it?” Lyons asks him with genuine interest.

“To me, when I watch, it’s aspirational,” Saint Sernin says dreamily. “Because they’re stunning, and rich, and stupid.”

In the lead-up to the season premiere in July, Lyons was preparing to hide. Her 16-year-old son son, Beckett, had, coincidentally but conveniently, recently set off for a camping program where he would be out of range. (“I’m no drama,” he told me at lunch a few weeks before. “She’s the drama.”) “I’m just going away,” Lyons said over lunch at Rockefeller Center of her own plans for her debut. “As soon as it launches, I’m getting on a plane and being as far away as possible with no cell service.”

There would be a quick stint at VivaMayr, the Austrian wellness clinic famous for its detox deprivation diet (“‘Continuous Bathrooming,’ as I will henceforth refer to it for the sake of politeness, would be a central theme of the week,” wrote Vogue, approvingly). Then on to Corfu, where she and her new girlfriend, the photographer Cass Bird, would board a yacht to sail the Greek islands with some friends. “Not my boat,” she clarified. “Someone who has money that I don’t have — their boat.”

It had the makings of a great Housewives trip, but you won’t see any of it on the show. “We watched an episode all together on the boat,” says Porch, who invited Lyons on the trip, but as for the yacht or its high-flying passengers appearing on the show next season? “No, I don’t think it was volunteered.” (He asked me not to mention the ship’s owners, citing security concerns.) More, probably, than any of her castmates, Lyons lives a life that is genuinely glamorous, but she is very judicious about what she’ll share. On the show, she parcels out little nuggets of intel but none of the petty bullshit that is the engine of reality TV, tearing up about a recent breakup but refusing to point fingers. “She doesn’t know how to be free and open and talk about life,” Erin Lichy, 36, another Housewife and a real-estate agent, complains in one of the season’s early episodes.

“I think they felt like I was being standoffish,” Lyons says of her co-stars. “They are younger than I am. They have a sense of abandon that I don’t have. And I can’t create that. I’ve spent so much time trying to be a boss, to be professional, to be thoughtful about the words that come out of my mouth.”

Reality TV tends to privilege a certain kind of personality: an immature narcissist with a flair for the dramatic. Lyons may have a touch of the narcissism required (“I’m obsessed with ’em because they’re obsessed with me,” she says, laughing and pulling out her phone to show me Instagram memes from the self-appointed “Lyons Lesbians,” with whom she has been DM’ing), but she’s also an experienced, corporate-trained 55-year-old adult. The show has to work hard to paint her as an inscrutable oddball. “Most girls in this group think Jenna is a total enigma,” confesses one of her fellow Housewives in the first episode. “She doesn’t like dill, but she loves parsley.” By contrast, Mary Cosby, one of the Real Housewives of Salt Lake City, married her stepgrandfather.

Whatever the reaction, there was every possibility that once the show was out in the world, it would cannibalize much of Lyons’s earlier renown, introducing her to a whole new generation, yes, but introducing her as this. “The thing I’m struggling with is I had an identity attached to my work and my accomplishments, and I’m very careful — I don’t want my identity to become wrapped up in the show,” she tells me. Whether that would be easier said than done was an open question. “I think it’s gonna be really different when it airs,” she says. “I think. I don’t know.”

At the premiere party at the Rainbow Room two weeks later, girls in heavy makeup took kissy-face selfies in front of the Real Housewives step-and-repeat as Lyons and her castmates circulated. Her co-wives were in the expected variety of spangled cocktail dresses; Lyons was in oversize jeans and an Oscar de la Renta cape. Cohen, in his best carnival-barker mode, quieted the crowd to welcome the new cast to the family. A hundred phones pointed toward the sister wives as the DJ spun and the ladies shimmied gamely — Lyons looking, it seemed to me, ever so slightly abashed. “I’m so excited for people to see this side of Jenna,” Ubah Hassan, 40, a Somali Canadian model and new Housewife, told me.

Cass Bird is FaceTiming me from the Hamptons. Six episodes have aired, and I wanted to know how she feels about her girlfriend of a few months appearing on reality television — a girlfriend she got together with in the sunny interval between the show’s being filmed and its starting to air. I sent her a text, expecting nothing. Bird is a more private person than Lyons, and Lyons had warned me that she didn’t think she would want to speak. But within minutes, a typing bubble appeared. “I love her to pieces and don’t want anyone else to look at her. Is my response,” Bird wrote. And then the phone rang.

When Bird’s face appears onscreen — salt-and-pepper braids, enviable tan — there is Lyons’s too, cuddled up and laughing right next to it. For a minute, they titter and spiel like flirty teenagers caught prank-calling. But then Bird turns thoughtful and ambles to another room with the phone. She doesn’t particularly want to talk to anyone about Lyons, she says, and the prospect of doing so makes her nervous. The two first met 12 years ago, but became reacquainted at a friend’s place in Brooklyn a few months back, after the dissolution of both the relationship Lyons tears up about onscreen and Cass’s own long partnership with Ali Bird, an agent with whom she has two children. “It was laughy and silly,” Bird says of their meeting. “We hung out and were like, Yep. She is an actual mutant. Which I know you know already.”

I wonder how the reality bargain actually plays out now that the show is airing. “She’s always been a public person,” Bird tells me. “It wasn’t like I was unaware of her size in the world.” So day-to-day, the public eye on Lyons, the commentary around her, the loss of control of one’s image that putting oneself in the hands of television executives and editors requires — it’s not an inconvenience, I asked, not an impediment or something that makes you nervous or uncomfortable?

“I would say it is all of those things,” Bird replies.

But they have watched a couple of episodes — “I fast-forwarded a few of the parts” — and her worst fears have not come to pass. Lyons, in fact, has emerged as the show’s early breakout star, and not for wine-tossing, table-flipping reasons. Sobriety is one of the great unpracticed secrets of maintaining one’s equanimity on TV. The show, for its own dramatic purposes, has had to play up Lyons’s coming out of her shell. That doesn’t mean Bird is eager to participate. “Never,” she says when I ask if we would see her on RHONY next season, assuming it returns and Lyons returns with it. (Too soon to say, Cohen tells me, though he hopes it will continue with the full cast.)

But the Jenna on the show, Bird admits, is a recognizable version of her girlfriend, a real reality star.

So the TV version is Jenna Lyons the character, I ask, and you’re getting Jenna Lyons the person?

“No, I’m not even getting Jenna,” Bird says. “I get Judy.”

Judith Lyons and her younger brother, Spencer, were raised in sunny California, just like the Housewives. Their mother, Barbara, was a single parent who worked as a piano teacher and with whom Lyons had an enduringly difficult relationship. (Barbara, who died about a month before the filming of Housewives began, was on the autism spectrum, Lyons says now.) The two were not close “at all,” and money was tight. “There were not a lot of funds,” Lyons says, and she was able to go to Parsons, where she rechristened herself Jenna, only thanks to a settlement from a car accident in her teen years. “Did you grow up with a lot of money?” she asks me at one point.

Six feet tall and ungainly by middle school, with incontinentia pigmenti on top of that, she felt estranged from the tanned Cali ideal. Lyons discovered herself through fashion by making clothes that fit her proportions. “I left California ’cause everyone was blonde hair, blue eyes, and big fake boobs,” she says. “I wish I looked like that. I just don’t. And, like, I tried desperately to do it, but it did not work. When I moved to New York, I was super-tan with ratty blonde hair and chicken cutlets in my bra.”

At Parsons, Lyons felt like a poor relation, obsessed with Calvin Klein and Jean-Charles de Castelbajac and Krizia but dressing mostly in sweatpants and vintage tees. Her roommate, the daughter of a wealthy Canadian public-utilities magnate, went on $10,000 shopping sprees. Lyons graduated in 1990 and took a junior position at J.Crew. She became a favorite of Emily Woods, one of the company’s co-founders, and glided through the ranks. It was a gig that lasted so long, and was so complete, that Lyons still refers to it simply as “my job.”

By the mid-aughts — as J.Crew was buoyed by the patronage of Michelle Obama, who as First Lady wore it often to signal her good-sense bona fides — she was making a significant salary and wielding significant influence. When she left in 2017, as president, she was responsible not only for J.Crew but for its little-sister line, Madewell, and all of the company’s Factory outlet collections and stores. “It always felt like she was the most popular person in the school,” says Jenny Kang Bishop, who worked at J.Crew as a stylist in the 2010s. “Everybody loved her. Everybody wanted to be near her. She was a star.”

Lyons’s was part of the sell. She shared her own style, which people copied, and her life, which fans admired. “Jenna’s Picks,” a section of the J.Crew catalogue in which she selected favorite items and gave styling suggestions, often featured pictures of her and her family at home. Lyons, who had married the artist and art director Vincent Mazeau, was seven months pregnant when J.Crew went public in 2006; Beckett began appearing in the catalogues as a toddler.

She had become the face of the company, the J. in the Crew. Her co-workers say her growing celebrity stemmed less from her own professed desire for the spotlight and more from J.Crew’s marketing department and Mickey Drexler, J.Crew’s CEO and her boss and mentor. But she proved very good at it. When they did company presentations together, Todd Snyder says, “I knew I was gonna have a tough time getting the microphone out of her hand.” The Kingdom of Prep, a book about the rise and stumble of J.Crew published earlier this year, quoted another former colleague: “She wanted to be exactly what she became — the attention, the accolades.”

Lyons became a target as well as an idol. In the spring of 2011, she endured a Fox News nightmare when she was photographed painting 5-year-old Beckett’s toenails pink, spurring a fatuous save-the-children news cycle. (Because J.Crew had just gone private again, in a $3 billion sale to two private-equity firms, it was at least not beholden to shareholder squeamishness on the subject.) But that was only a taste of what she would endure that fall when “Page Six,” the New York Post gossip column, published an item outing the newly separated Lyons.

J.Crew was supportive, but the experience was bruising. Her mother, she has said, was ungracious. Lyons and Mazeau divorced, and she began her first relationship with a woman in earnest. “I didn’t even know that I wasn’t myself,” she would later explain to her fellow Housewives.

She would remain at J.Crew for six more years, but they were increasingly difficult ones. Saddled with debt from its sale, the company struggled, and tastes moved away from Lyons’s quirky style. Having been given much of the credit, Lyons now found herself receiving much of the blame. She decided to step down and was allowed a queen’s abdication — roomfuls of employees toasted her with Champagne. There had been rumors she might go, says Bishop, but even so, “it was hard to imagine J.Crew without Jenna.” Drexler would step down only a few months later.

J.Crew had given her the kind of financial stability she hadn’t had as a child — her salary was in the seven figures, and she stood to benefit from both J.Crew’s IPO and its subsequent sale — but after leaving, personally and professionally, she was at sea. Her relationship ended after six years. When she created her own company, the umbrella for her various projects, she called it Lyons L.A.D., for “life after death.”

It was around this time that she met Bouttier and his partners at Magnet Companies, which funds start-up commerce businesses with private-equity cash. She was toying with the idea for Stylish, a competition show that, on the face of it, seemed to be about Lyons’s search for an assistant for her company, though what that company would be, and what that assistant would do, was unclear. The show was designed to bring viewers into Lyons’s world, and Bouttier envisioned it as a launchpad for an e-commerce marketplace where Lyons’s taste and “picks,” as in the J.Crew days, would once again be shoppable: things she manufactured as well as things she selected and curated.

Stylish was a victim twice over — of its many perpendicular aims (was it a competition show? A reality show? An infomercial for Lyons’s company?) and of the corporate realpolitik of the Warner Bros.–Discovery linkup, where the prestige of Warner-owned HBO was grating against the homeyness of Discovery. Kyle DeFord, Lyons L.A.D.’s chief of staff and Lyons’s gay Friday on Stylish, decamped to work for Drexler, who had taken up residence at his son’s J.Crew-ish clothing company, Alex Mill. For the moment, Lyons had one product, LoveSeen eyelashes, and she needed to sell them. Then, at a live podcast taping at The Wing in the winter of 2021, the two hosts of Dyking Out suggested The Real Housewives.

Back in Soho, Lyons is wrapping up breakfast. Her assistant has been frantically calling; Lyons, the Housewife with not one job but many, is late for her next meeting. She starts a power walk back to her apartment, which, like her old Brooklyn brownstone, has been photographed, published, and obsessed over. “Love you on the show!” calls out a girl on the street.

Lyons is a hit. Those who love the messy Housewives had worried about the media-trained, reared-on-reality women who replaced their predecessors. Were they “new shiny hood ornaments,” where “we were all train wrecks,” as Bethenny Frankel opined — Frankel, who was promoting a would-be revolution to unionize reality performers just as rebooted RHONY debuted. But Lyons in particular has been embraced. “I am holding off on officially judging most of the women until episode five, but I am obsessed with Jenna Lyons,” one recapper wrote. “I have never felt there was a Housewife who was aspirational until we met Jenna, and the more we know about her, the more I absolutely stan.” “Can you imagine how badly this new RHONY would suck if they hadn’t added JFL late in the game?” (That’s “Jenna Fucking Lyons,” which she jokes on the show should be her monogram.) The other women may not have known what to make of Lyons — whose name they tend to use in full and in a single breath, “Jennalyons,” like a brand — but viewers do.

The show is a more qualified success. Initial linear-TV ratings showed a continued drop in viewers from previous seasons. Peacock, the NBCU-owned streaming platform that also airs the episodes, doesn’t reveal its numbers. NBC brass did crow that RHONY’s season-14 premiere attracted more than 2 million viewers across platforms in its first seven days and was Bravo’s most-watched season premiere in Peacock history. “Any time anyone posts ratings for live viewing, it doesn’t mean anything because that’s not how ratings are measured,” Cohen says. “I measure success by how the fans are reacting to it, and they are embracing it. And that’s as much as I or any of us could have hoped.” But nothing in the season so far has come near the moon shot of Vanderpump Rules and its recent “Scandoval.”

That’s not to suggest that RHONY has been without its own scandals. A TikToker using public data discovered that Lichy had donated to the Republican Party’s political-action committee WinRed immediately following the November election — in essence, he inferred, to Trump’s “Stop the Steal” campaign. Headlines circulated that she was an election denier, and Lichy was forced to issue a statement that she had never supported “Stop the Steal.” Lyons is a well-known Democrat—she is not shy about sharing life lessons learned from the Obamas — but she expresses only sympathy for her castmate. “I feel terribly for Erin,” she says. “I’m used to things being written in the press about me that are not true, but I think she felt really upset. She’s not a Trump supporter. She is not in any way, shape, or form an election denier. She just somehow donated to something that she did not realize had connections to that. And now she’s getting sucked into it.” (“I was an early-on supporter” of Trump’s, Lichy said on a recent podcast. “I thought he was going to be really good for Israel … People’s views change.”) Her advice to Lichy, in the group chat the women keep and to which Lyons doesn’t often contribute, was to wait it out. “You are not big enough to hold the news for that long,” Lyons told her.

So far, Lyons has avoided any such drama. Her life, she says, is not much different than it was. Her Instagram following has increased, that’s for sure, from around 200,000 people when we first began meeting to almost 600,000 now. She has worked LoveSeen into the show over and over, from her opening-credits tagline (“My lashes may be fake, but I definitely keep it real”) to a model casting in a recent episode. Her fellow Housewives may complain — “Everything’s a branding opportunity. I can’t stand it,” says Brynn Whitfield (age: 36. Tagline: “I love to laugh, but make me mad and I’ll date your dad”) in one episode — but the impact it’s making on the business is real. “It’s been a multiplier effect,” Bouttier told me when I called him back a few weeks into the season.

At Lyons’s loft, she jumps into one iPad-enabled meeting after the next. On social media, her team had offered buyers a perk that the show could only have sweetened: Buy a pair of LoveSeen from Target and Lyons will Zoom you through a ten-minute application tutorial. A smiling blonde attorney in Nashville named Savannah pops up on the screen. Demonstrating on herself, Lyons guides her through fitting a LoveSeen lash. “Don’t be afraid. Get in there!” Lyons says with the barest edge of flirtation as she suggests other LoveSeen products Savannah might like (“With your lighter skin tone and blonde hair, it might look really pretty”). Lyons has a gift for establishing immediate intimacy, though the prospect turns exhausting when it becomes clear this is the first call of many. “I’m booked through October,” she says. “It’s easier to do them back-to-back ’cause it’s all set up. But the thing that happens is after I put the seventh one on, my face is caked in glue, which is not chic.”

Another call begins. Lyons continues to work with friends on home-design projects, but for not-yet-friends she offers one-on-one consultations via the Expert website, a kind of Cameo for design gurus. These sessions cost $1,500 for 55 minutes, and the site says she is in its top-ten most-booked designers. Now, a team of Expert staffers appears onscreen to help Lyons stock her online “showroom” (she gets a percentage commission from the sales). A new round of friendly, sales-y preamble: “How old is the baby?” Lyons remembers to ask someone.

Before the work begins, the chat turns inevitably to Housewives. “You’re in the center of the storm right now, I imagine,” someone says.

“I’m really not,” Lyons replies. “It’s so funny. I was just talking about that. I think it was much more chaotic when we were filming. Now, I don’t feel like I’m the center of anything other than my own deep, dark thoughts.”

Lyons’s time at J.Crew — as savior, then star, then punching bag — is still, five years later, never far from her mind. “Culturally, we want the underdog to win,” she had told me a few months before Housewives hit the air. “But as soon as they’ve won, then we’re like, ‘Okay, well, wait, wait, wait, that’s too much. You’re the underdog and we’re gonna lift you up, or you’re way up here and we’re gonna try and take you down.’” Lyons knows from experience. Or as she puts it to her needling fellow Housewives, “Yeah, I’m fucking guarded. I’ve been fucked so many times.” She also knows that work must be done to keep the crowds watching, to keep the machine fed. You’ve got to be Seen to be Loved.

This story has been updated to more accurately reflect how Lyons and Cass Bird met.