Part manifesto, part workbook, Jezz Chung’s This Way to Change is worth taking in slowly. The book is grounded in a teaching from Grace Lee Boggs — “Transform yourself to transform the world” — and may remind you a little bit of The Artist’s Way and kamra sadia hakim’s Care Manual. It was originally pitched as a workplace survival guide for people of color, but once Chung started writing, they quickly realized they didn’t want to center the workplace at all. They also felt resistant to telling other people what to do with themselves. “I can’t change someone’s life,” they tell the Cut. “I can only create space and share resources for people to change their own lives.”

In 2020, Chung quit their eight-year advertising career and took the risky leap to become their own boss as an artist, poet, and performer. As their life changed, so did the book they were writing. “I wanted to divest from systems of harm and design a life of care and a life of agency and choice and one that aligned with my values of healing, care, and collective liberation,” says Chung. “This book is an archive of that process.” In poetry, prose, and reflective practices, the three sections — “This Distance,” “This Difference,” and “This Dreaming” — map out a liberated future by closely inspecting the past and present, both in Chung’s own life and in the wider world. More than anything, they describe themself as a student of movements, from disability justice and queer liberation to Black Lives Matter and the movement to free Palestine. “Every movement for liberation is connected,” says Chung. “We’re all interconnected, and every movement for freedom and liberation throughout time has happened because people believe that change is possible.” Below, Chung shares five of the projects that helped inform and inspire their work.

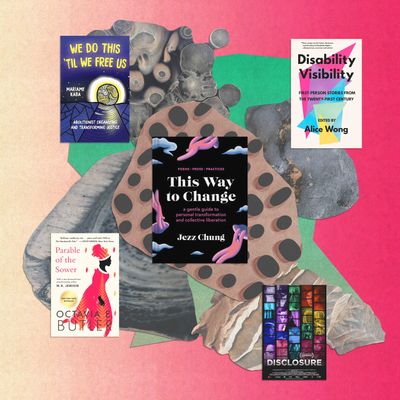

Disclosure, directed by Sam Feder

It was so important for me to have a single resource that I could point people to to be like, “Hey, this is the state of transphobia in this country. This is why there’s so much transphobia. This is why trans people are killed. This is why there’s so much violence against trans people.” Disclosure feels like a comprehensive way of looking at the landscape of how trans people are seen in America and why — especially the why.

I wrote about it in an excerpt titled “Unlearning Transphobia,” and I talked about how in order to address transphobia, we must be able to identify it. Collectively, we’re able to identify racism pretty skillfully — but transphobia and ableism, not so much. Our collective literacy on it is very low. I wrote that transphobia is so prevalent in our culture that no one has escaped its influence. It requires active undoing.

Disability Visibility, edited by Alice Wong

Reading Disability Visibility was the beginning of the revelation that I’m disabled and have had disabled experiences. There is no such thing as being late in your journey. You can realize that you’re queer at any point in life. You can also realize that you’re disabled or neurodivergent at any point in life. I write about a lot of that change that I experienced when I realized I am disabled and neurodivergent. This is why all these experiences have been hard. This is why I felt so different throughout my life. The power of it also reminds me of the power of firsthand stories and the importance of archiving these stories from people we haven’t historically heard from.

We Do This ’Til We Free Us, by Mariame Kaba

I love how We Do This ’Til We Free Us had all these examples of how people are practicing abolition already. It’s so much about practice: What does abolition look like in practice? What does abolition look like in conversation? What does abolition look like in relationships? A third of my book is practice. I was reading We Do This ’Til We Free Us while writing this book — because I fall into pits of despair all the time — looking at the state of everything and thinking, We can’t even secure health care in this country. How are we going to get to this future where everyone has their needs met so that people don’t have to resort to crime, so that we don’t put people in cages, so that we don’t need this level of policing that is so harmful and violent? Well, who has done it? Who is doing it, and who knows way more than me? I love the work of Ruth Wilson Gilmore and love Mariame Kaba’s work because they’ve devoted their lifetimes to this. I’m a student of their work, and I very much resonate with these concrete examples and ways to put all these theories into practice.

Parable of the Sower, by Octavia Butler

In my book, I have a poem titled “Future Parable,” and I talked about how so many people I know started reading Parable of the Sower when the pandemic started. It parallels everything going on right now. I related a lot to it because the main character has hyperempathy syndrome. That has been my life. I have been debilitated, paralyzed by other people’s pain and by witnessing collective pain. That book was so formative in helping me understand how to embrace change. Like Octavia Butler says in the book, “All that we touch we change. All that you change changes you. The only lasting truth is change.”

That’s become a thesis for my life, a motto that I live by. I can see change is a lifelong process instead of thinking that I have to do everything now and fully change myself now and fully heal now. No — healing is changing, and growing is changing, and all of that has incremental steps. I have to trust that every book that I read, every show that I see, every conversation that I have, every piece of art that I consume or make changes me. That also keeps me really focused on being intentional about what I consume.

All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, directed by Nan Goldin

I love Nan Goldin’s commitment to calling things the way they are and making people aware of what they are participating in. Over the past few months, we’ve seen a lot of protesters shut things down — disrupt spaces, disrupt museums, disrupt public events — and these disruptions are so important. It’s a sign of something larger.

If people’s first reaction when seeing someone disrupt a space is frustration or judgment, I really urge those people to ask what those people are being disrupted by. Why are those people being so disruptive? It’s because genocide is really disruptive. Food insecurity is really disruptive. Climate crisis is really disruptive. Inflation is really disruptive. Watching Nan Goldin disrupt the Met like that was so iconic. She put herself at risk. I don’t like thinking in terms of binaries, but when something is so blatantly wrong, we have to call attention to it and decide that we can’t accept it as it is. Having an artist who has such an expansive body of work and who is so established in her career take initiative like that — I think we need as many examples of that as we can find.