If I knew how depressed I’d be in the weeks after my breast-reduction surgery, I’m not sure I would’ve been brave enough to go through with it.

It was the spring of 2023, two months after my divorce was finalized. I had moved to Los Angeles four months earlier, a year after my ex left me and the Brooklyn apartment she never quite moved in to. 2020 through ’22 were an unpleasantly busy few years, beyond the obvious: I moved cross-country three times, from New York to San Diego, then back to New York, then back to California, L.A. this time, alone. Moving to L.A. was just one of several big decisions I rushed to make postdivorce, when I needed everything about my life to change as quickly as possible so I could once again feel in control. I quit my job, I joined three dating apps, I shopped irresponsibly, and I let a stranger cut off my shoulder-length hair. She showed me a picture of Kristen Stewart, and I wanted to believe, but back at home I looked like a gay brunette Kate Gosselin.

While I’d managed a mid-level disdain for my breasts since they appeared, seemingly overnight, when I was 19, I suddenly couldn’t stand them a second longer, either. An eventual, hypothetical reduction had occurred to me in recent years; I raised the idea with my ex once or twice, half because I meant it, half because I knew she’d object. As soon as I became single, I began seeking intel. A number of friends and friends-of-friends had recently gotten breast-reduction surgery, which the New York Times reports has risen 64 percent since 2019. Everyone I heard from was unreservedly thrilled with their new smaller chests.

When an L.A.-based internet friend posted a selfie featuring her own breast reduction, I asked for her surgeon’s name and made an appointment. As is always the case with any kind of authority figure, I expected an interrogation, maybe even a refusal, and was both relieved and vaguely disappointed when the consultation was over in 20 minutes. My surgeon wrote a letter to my health-insurance company arguing the procedure was medically necessary; you’ll never believe it, but it disagreed. My surgery would be very expensive, but I felt entitled to heartbroken spending: I had enough money to pay out of pocket because of an unexpected tax return, thanks to a new accountant who corrected the mistakes of the old one. Change was good.

On the day of my surgery, the doctor drew a purple B on each of my shoulders, a slightly discomfiting reminder of the cup size I had in mind. I was, as always, convinced I was medically special, and the anesthesia wouldn’t work, and told my doctor as much. Just as I had when my wisdom teeth were removed, I counted down from 100. I remember 97, then nothing.

I woke up three hours later, apparently kicking; my new girlfriend, Mary, whom I had met the day after I landed in L.A. (I loved change!), waited in the lobby and told me she heard the nurse instruct me, repeatedly, to put my legs down. When I sat up, the nurse told me I could go home. I went into comedy defense mode and asked just how the hell she thought I should get there. She rolled in a wheelchair and, along with my girlfriend, ferried me out to my car. On both sides of my torso, plastic tubing poked through my skin, collecting my blood in a pair of bottles that hung at my sides. Never before in my life have I been so painfully aware of every pothole and bump in the road.

When we finally got home, I slept for hours. When I woke up, I looked at myself in the mirror and I panicked: What have I done?

My poor breasts: I wanted them for so long and then when they showed up, I complained. I was an underdeveloped teenager, flat as a board front and back. In seventh-grade earth-science class, I sat beside two popular girls and behind two popular boys, and once, while I filled out the group worksheet, the boys commented that Kelly had Grand Tetons, whereas Lauren had Regular Tetons. Unsophisticated humor, nothing like the avant-garde comic strips I drew between classes for Kelly, but still, one wants to be included at 13. I believed I’d embrace Tetons of any size, so long as there was something beneath my Express shelf-bra tank tops — and for a brief window, I did.

A pair of honest-to-God jugs arrived just in time for binge-drinking and $10 going-out tops from Forever 21 and, relatedly, a fledgling awareness of my sexual power. At frat parties, I’d lean over the beer-pong table to distract my opponents; my Halloween costumes were reverse engineered around bras I acquired at discount at Victoria’s Secret, where I worked summers and holidays. By day, I was the president of the campus Feminist Majority Leadership Alliance in a button-up shirt and sweater-vest. By night, and drunk, I was Lara Croft. I liked the attention, mainly for the element of surprise, like a magician lifting a dove from a top hat: You didn’t expect to see that, now, did you?

I derived no physical pleasure from the few men I let fondle me, but it can feel good to make someone else happy. Virtually everything in my life changed when I began dating women, except this: My breasts were for other people to enjoy. But by then, well outside the discovery phase, I began to recognize they had little to nothing to offer me.

For a decade, I camouflaged my breasts beneath black T-shirts, black sweatshirts, and poor posture; getting comfortable with my sexuality freed me of any desire to display cleavage in public and, in fact, made the very idea of men ogling me repulsive. I wanted my girlfriend to find me attractive, but I wasn’t worried about anyone else. In adulthood, my preference has been to perceive my body as a container for my brain, the part of me I actually care about. I don’t always succeed, but I’m happiest on days when my physical form doesn’t intrude on my life.

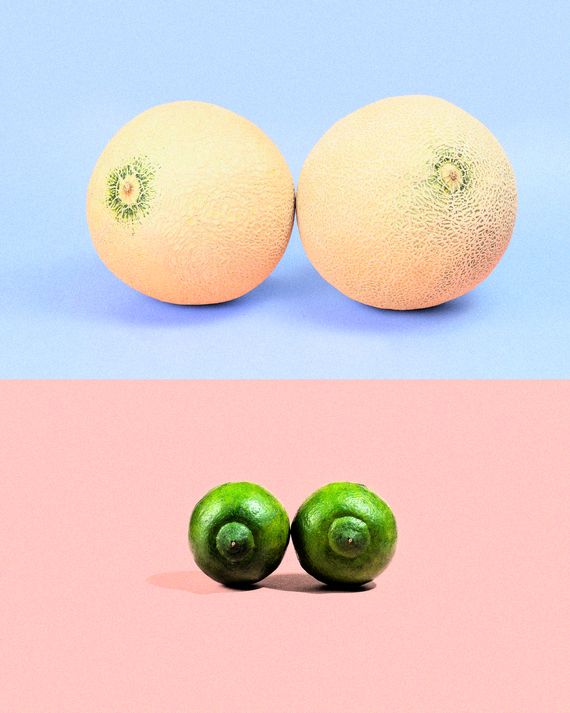

All my breasts did was get in the way. They stretched out my shirts and pulled at my buttonholes. They projected femininity, but I preferred to look tomboyish. They hurt when I exercised. They moved around too much if left unrestrained, so I slept in a bra, and that hurt, too. I kept my shoulders rounded and my arms crossed, and I succeeded well enough that whenever the subject of breasts came up between friends, my credentials were occasionally dismissed by women with bigger ones. What could I do in that situation except pull my shirt tight and submit myself for judgment? I feel strangely defensive even now, five pounds of evidence long since excised and incinerated. All that’s left now is my own urban legend: Once upon a time, I had boobs like you wouldn’t believe.

The drains at my sides hurt more than I expected them to, but in that first week, they gave me something to focus on: They needed regular emptying and careful positioning; everything would get easier once they were out. I didn’t think much about what getting them removed would entail or expect to go faint as the nurse tugged the tubes from inside my body. The popsicle the nurses brought to revive me was excellent, and I hoped that, from there, things would only improve. And physically, they did: Without a constant sting at my sides, I could finally sleep for more than an hour or two at a time.

But once the pain lessened, there was more room for despair. I guess I was naïve, but I did not expect so much weeping. Had the surgery been required — a mastectomy, an amputation — the devastation might have felt earned, but I’d chosen to do this myself, which meant I felt responsible for my sadness. When I looked beneath my surgical bra, while my girlfriend helped me change the bandaging, I felt like Frankenstein’s monster, and it was all my fault.

Sometime during week two, I felt low enough to send my doctor a mental-health update, a kind of hopeless FYI. One of the nurses emailed me back. She said what I was feeling was not only normal but common: Poor reactions to anesthesia and/or pain medication, as well as the general physical stress put on one’s body during surgery, can result in postoperative depression. This was comforting to hear, but it also made me wonder why nobody warned me before.

After a month, I was allowed to exercise again, so long as I didn’t lift weights. After six weeks, I was allowed to walk my dog. In that time, my hair grew approximately 0.6 inches: almost chin-length on the right, almost ear-length on the left. My breasts sat oddly high on my chest, still swollen from the surgery. I would need to wear a bra 24 hours a day for a year to prevent sagging, and while I felt they could frankly stand to drop a few inches — and while the ability to go braless was one of the surgery’s main draws — I did as I was told.

My scabs healed, and I started wearing silicone tape meant to reduce scarring. When the pain was gone, a near-constant itchiness took its place, and the tape exacerbated it. I turned to r/Reduction on Reddit, where I found lots of people with the same reaction. When I texted my surgeon’s office about how badly my scars itched, it was suggested I take breaks from the tape. I did, and it helped a little, temporarily, but I didn’t want to give up. The pictures my surgeon had showed me featured thin white arcs under his patients’ breasts, but my scars were raised purple welts: either hypertrophic or keloid scarring — he wasn’t sure which. Every time I went in for a follow-up, we’d commiserate over shared disappointment. I didn’t want him to feel bad, so I talked about my body like bad weather nobody saw coming. Meanwhile, his surprise at the severity of my scars only compounded my remorse.

Eight months or so after surgery, when it became clear no amount of silicone tape would flatten my scars, my surgeon offered to perform a scar revision, which meant he’d cut out my scars and sew me back up with a different kind of stitch in hopes I’d heal better the second time. This process was “not uncommon,” he told me, which again made me wonder why I was only now finding out. The procedure would be free except for the cost of an oxygen tank: Like most of his patients, I would be awake for my revision, placated by local anesthesia, Xanax, and laughing gas. I scheduled the appointment for February, 2024, ten months after my reduction.

In his office, before being taken into the operating room, I asked the nurse if it ever happened that laughing gas didn’t work or, rather, if it ever made things worse. In the two years prior, I had largely quit weed and alcohol, having become increasingly sensitive to both, finding they only made me more anxious than my anxious baseline. I worried aloud to the nurse that the laughing gas might do the same. She reassured me: No one didn’t like laughing gas. It would help me dissociate from my body and what was being done to it.

A thin blue curtain was hung between my head and the rest of my body, blocking my view. At last I was a floating brain. The nurse wheeled an oxygen tank alongside me and handed me the tube. “This is all yours, so inhale as much as you’d like,” she said, taking a position of guardianship behind my head as the surgeon prepared to inject me with anesthesia. I bit down on the plastic tube and breathed in. My skull seemed to expand and lose mass, a balloon that might float away. Maybe some people enjoy this feeling, but I did not. Maybe it was my fault: By fearing the worst, I made it happen. But when the surgeon began to slice through my skin, I felt everything. I groaned and writhed. “Suck in,” the nurse told me again and again. The surgeon injected more anesthetic and tried again. I obeyed. But I could still feel myself being cut, and soon tears were streaming down the sides of my face.

The surgeon and the nurse discussed what to do with me as if I were not there, but I was there, hearing and feeling everything. I began to sob around my oxygen tube, which made my body shake, which frustrated my surgeon, who told the nurse he didn’t want to hurt me. He asked if they might give me fentanyl, but the nurse refused, not without an edge to her voice. She petted my hair, her blue-gloved hands rubbing circles into my temples while I wept. It was decided this wasn’t working, but my body was still open. The surgeon still needed to close it. I asked for a break first and then I cried while he stitched me together.

The plan was to remove and revise my anchor scars on both sides as well as the raised rim around my right nipple, but I made it through only one, under my right breast. The failure to finish what I’d started only sharpened the pain. I couldn’t look at the nurses or my doctor; I didn’t want them to say another word. I let myself be wheeled toward the waiting room, weeping. Mary rushed over, held my head to her stomach. She drove me home and put me to bed. While I slept, she went to get me a Shamrock Shake from McDonald’s — one of late February’s few mercies — and it helped for as long as it took me to consume it.

Later, I am told the way I reacted is rare; most people my doctor treats do well with local anesthesia. Still, he and all the nurses sympathize. They can’t say sorry, exactly — for liability reasons, I assume — and, anyway, I’m not sure it’s their fault. I’m angry, but there’s nowhere fair to direct it. I can’t even be relieved, because two-thirds of the job is unfinished. My surgeon tells me he’ll fix the remaining scars — but put me under this time. The revision is covered, but I’ll need to pay a $1,350 deposit for the anesthesiologist.

I scheduled the appointment and paid the deposit because I wanted to be done. I wanted to look how I’d imagined I would look. I wanted to get past the pain quickly, as if there were a finite amount allotted to me and I could fast-forward through it.

The incision beneath my right breast began to heal and then scar, looking very much like it did before. At the same time, I found myself consumed by a new fixation: the skin between my chin and my neck, which no one on television has anymore. I pinched at it, studied it in the mirror, and sent a selfie to my best friend, who claimed never to have noticed. I absorbed entire reality shows without watching anything but anyone’s jawline. I could see it now: This is how it starts. Having tried to correct just one thing, I simply moved my target.

And when my presurgery instruction email arrived — reminding me to fast, remove all my jewelry, shower with harsh antibacterial soap, wear loose-fitting clothes day of — I had a panic attack. I canceled the appointment, requesting a video call in its place. Mary held up my phone’s camera to show the surgeon the newer of my two scars. He agreed it didn’t look much different and said there was no guarantee the other revisions would fare better; each and every incision carries a risk. Again it surprised me how much nuance was articulated after the fact. Beforehand, all I remembered, all I perceived, was confidence. But I am that way, too: black-and-white bravado well before I’ll admit to gray.

My deposit was returned to me. I wished the same were true of the laughing-gas fee: $200 for the least-fun drug experience of my life.

On certain days — mainly when I feel broke — I wish I had it all back. Although it was money I never expected to have, $19,000 is an awful lot of money. It’s impossible for me not to wonder if I might be happier now had I saved it and continued to live with my body as it was. Like most people who pursue cosmetic surgery, I believed I’d made a decision for and by myself. But what if no one had ever commented on my breasts, or the prior lack thereof? What if I hadn’t seen 50 million TikTok videos of young women with flat chests in baggy T-shirts? What if my doctor had told me that I might be depressed for a month and my scars might look much worse than the pictures in his portfolio? Would I still have done it?

Less often, and less practically, I worry, too, that by giving up breast tissue, I’ve sacrificed some future, as-yet-discovered version of myself: What if one day I want to dress like Sydney Sweeney but no longer have the rack for it? Never mind that I’m a homebody writer and almost 40. Never mind that I stopped showing any cleavage 15 years ago. I’m more than capable of feeling regret for not doing things I never wanted to do in the first place; I do it all the time.

It’s been more than three years since my separation, almost two since my surgery. My appetite for big changes has all but evaporated. I understand they’ll come anyway. I don’t want to claim I’m any more prepared for change now than I was before, because that feels like a dare, and I’m superstitious. But when I look at my chest in the mirror, and see how the unrevised scar beneath my left breast has started — so slowly — to flatten, well after I believed it could, I feel largely indifferent. In a T-shirt, and a wireless bra, I feel better. I didn’t achieve the perfect, permanent satisfaction I desperately craved. Everything takes more time than I want it to. But Mary says I stand taller now than I used to, and my hair has almost reached my shoulders.