This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Judy the psychic’s feet were firmly planted on the floor of the cramped, windowless room, her petite body rocking slightly as she stood in the corner. We were tucked away at the back of Crystal Vortex, a shop in Sedona, Arizona, where she was giving readings. My decision to see her while on vacation had been spontaneous, made while perusing the citrines and pyrites up front. The cramped space was occupied mostly by a large wooden table neither of us sat at. My chair turned out to better face Judy. “I like to be a pendulum,” she explained, “to sense where the energy is.”

The half-hour reading was mostly a meandering fishing expedition that matched her swaying, until she asked, “Is there anyone who’s passed on that you want to connect with?” I clenched my teeth and nodded. “Give me a name,” she said.

“Guadalupe.” My maternal grandmother who lived with us and helped raise me and my siblings. Judy swung to the right and instantly connected to her.

Judy tapped the tops of her fingers and said my grandmother was happy I was using her jewelry. My hands were bare during the reading, but I had, in fact, reset her diamond-anniversary ring to wear as my wedding band a few years earlier. Then Judy began rubbing her thumbs in a downward motion along the sides of her index fingers. “She’s indicating something about … a necklace, maybe?” Judy guessed. I frowned, unsure. “Something about beads …,” she continued. Staring at Judy’s fidgeting hands, a sudden wave of chills ran from the top of my head down my shoulders; it felt like my lungs had sunk down into my stomach as the chills rolled down my back. I recognized that gesture. It was the way my grandmother’s hands moved down the Rosary she prayed over every night. She and my grandfather moved in with us when I was 6, and we’d rarely spent a night without her 53 Hail Marys. Through birthday parties, sleepovers, even vacations, the hour-long supplication to the Virgin Mother, for whom my grandmother Guadalupe was named, was a nonnegotiable.

Eventually, once I left for college and moved out on my own, I forgot about the bedtime ritual. Now in my 30s, I’d spent the past four years zigzagging through different spiritual practices in hopes of reconnecting with something in my own way. It began around the time my grandmother died in May 2021, when my first niece and goddaughter was 7 months old. The whirlwind of funeral, birth, baptism, and burnout brought me back to a question I hadn’t thought about in a while: Why am I here? I started by scheduling readings with astrologers for a deeper dive into my birth chart; I used my birthday party as an excuse to hire a tarot-card reader; I devoured books on anything and everything occult; I had a massage focused on releasing blocked energy – an hour-long session spent stretching out my hips while I cackled uncontrollably, supposedly a sign of trauma release; I found a therapist who introduced me to trance work and hypnosis. Every time, I felt myself moving even further away from the devout Catholic upbringing my grandmother made sure I had.

She was a stern, no-nonsense woman. An intimidating matriarch whom I feared more than loved. There, in the room with Judy, I felt a warmth and tenderness that I had never witnessed from my grandmother as a child. I asked if she approved of my spiritual journey, something I would have been terrified to ask if she were still alive. Judy placed her hand over her heart and nodded as she opened her eyes to look into mine. “She does, and she’s proud of you,” Judy confirmed. “Catholicism was her way, but she says what is really important is prayer. It can be in your own way but always find a way to pray.” Relief spilled out through my tears as Judy smiled back.

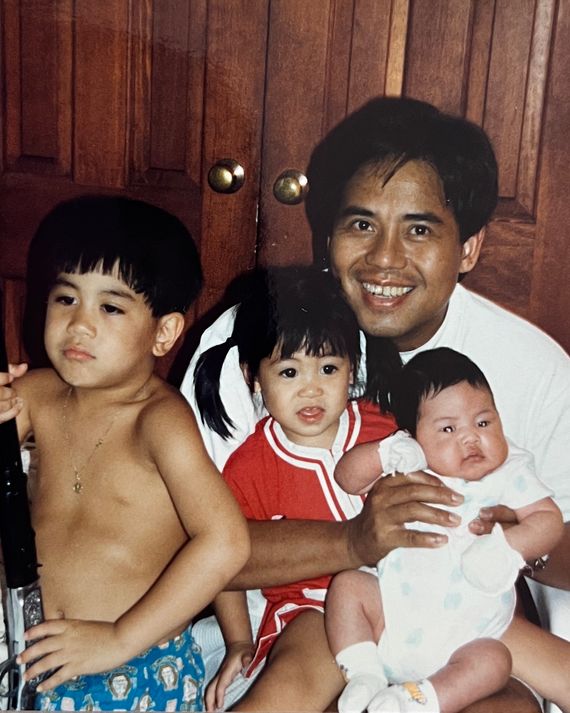

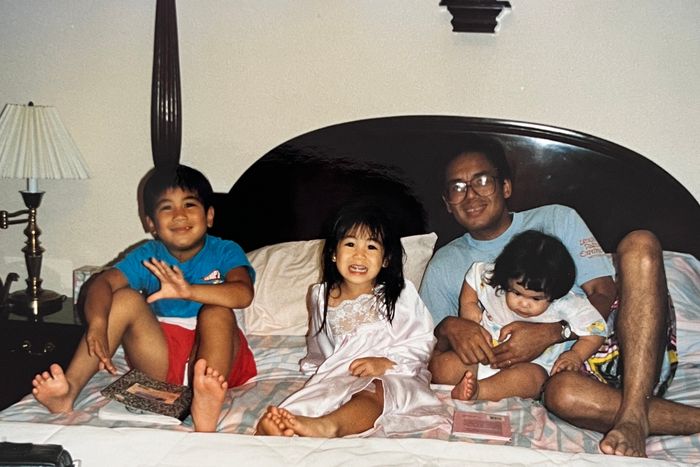

Judy asked if there was anyone else. I hesitated before saying my father’s name. He died just a few months before my 3rd birthday, and for most of my life, that was one of the few things I could tell you about him. My mother rarely talked about him, never recalled fond memories or shared stories. Even the exact cause of his death — cancer, I think? — had always been foggy to me. Once when I asked my mother how my father proposed to her, she shrugged: “He just asked.” The message was clear: Mom didn’t want to talk about him, so I stopped asking.

“Danilo.”

As I said the final syllable, the warmth I felt from my grandma was instantly sucked out of the room. I caught myself holding my breath and then gulped down too much air all at once, coughing awkwardly. There was no swaying this time. Judy, with her eyes closed, brow furrowed under her silver bangs, stood perfectly straight, completely still. “He’s here … he’s giving me a stern … I’m sorry, it’s a no. He doesn’t want to talk.” Judy looked at me with apologetic eyes. She didn’t understand.

Maybe he feels ashamed, I figured. I didn’t know everything, but I knew that in my gut.

After my reading, between the Arizona red rocks and under infinite stars, my friend Tate told me about connecting with her grandmothers through a reading with a woman named Fallon Stone, a licensed psychotherapist and intuitive mentor. “I really think you should talk to her,” she said. Less than a week later, back home in New York, I booked Fallon’s earliest available telehealth appointment, ready to throw down $175 for an hour I hoped would give me the answers I hadn’t gotten on vacation or at any other point in my life.

Fallon’s serene face smiled at me from across the internet as she took a deep breath in. “There’s a lot here,” she said. I chuckled.

“The energy I’m getting is a lot of secrecy,” Fallon continued. “When I tune into your dad’s energy, he’s in the background and I feel shame coming from him, almost like he doesn’t want to come out from around the corner because he doesn’t know what’s going to be projected onto him.”

Even though I couldn’t see or hear what Fallon could, that energy was unmistakably familiar; a feeling of being suffocated by all the things my family, dead and alive, has left unsaid. It was isolating and lonesome, which Fallon clearly sensed, asking if I was an only child. I actually have two older siblings who I’m close to, and Fallon wondered aloud why they felt so far away, energetically-speaking. She closed her eyes for a beat and nodded. “They have a completely different purpose,” she confirmed. “We’re on the subject of your purpose, and I see you alone in that. And there’s so much strength and courage in that.”

It was lonely navigating this strange space by myself, though, and I was uncertain about where to go from here. “It’s really important that you take this process that’s actualizing through you and move it through somewhere,” Fallon continued. “Your ancestors keep calling it a story. Spoken or written, it has to move through you.”

As we talked, Fallon sensed that my dad was feeling more trusting. I straightened up in my chair. Maybe my loneliness and confusion resonated with him, I thought. “I can still feel him in the background” she said, “but he’s saying ‘I give you permission. My story needs to be told.’”

“I would love to tell it!” I said, laughing, throwing my palms up toward the sky as if the truth would fall into them. “But first I would like to know it.”

Fallon asked if there was anyone alive who might know more, someone close to my dad. I knew what my dad was saying without having to hear it: “You need to talk to your mom.”

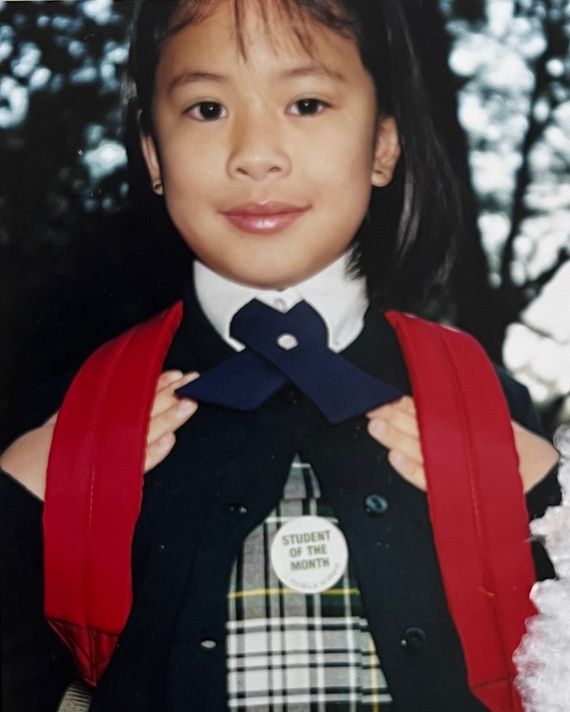

In third grade, my Catholic school uniform included a bow tie that snapped together across the most tender part of my neck. I could feel it digging into my throat one September morning when our teacher asked if anyone had any special intentions during morning prayers. The audible gasp that came when I asked the class to pray for my maternal grandfather, who’d died earlier that morning, took me by surprise.

“At your house?” someone asked from behind me. I nodded. Another gasp. I felt my chest tighten. Another classmate gawked at me and asked, “Why are you here?”

I wished the bow tie had choked me out before I spoke. Death, I realized quickly, was foreign, if not deeply unsettling, to an audience of my fellow 8- and 9-year-olds. To me, it was nothing new.

A few years after my dad’s death, my paternal grandparents died one after the other in the Philippines – my grandfather from illness, my grandmother from heartbreak. This was 1997, the same year Princess Diana died. I remember watching the news, surprised at how people who had never actually known Lady Di could speak about her with such emotion. Why did no one in my family ever speak of our dead like that? If they even spoke about them at all.

Somber church services were the only consolation my siblings and I received for these back-to-back deaths. Grandma Guadalupe, who along with her daily Rosary also attended daily Mass, had a habit of inviting priests and seminarians over for coffee and Entenmann’s pastries after services to impart their holy wisdom to us, like the fact we all must die one day but our reward was an eternity with Jesus in heaven. I’d smile politely as I cut a slice from my grandmother’s favorite boxed danish ring.

My young brain didn’t need a holy man to piece together the inevitability of death. The real question was, When would it be my turn? When would I be reunited with my family? Surely it would be soon, since I felt so unwelcome where I was. We were the only family of color in my neighborhood along the north shore of Long Island; our summer days were spent at the small beach down the road,usually accompanied by suspicious stares. Mom was always at work, so I quickly learned to handle the occasional interrogations from older women myself: “Do you belong to this beach club? Do you live in this neighborhood? Well, where exactly do you live?” Occasionally, these vigilantes wouldn’t interact with us at all, providing some temporary relief until the local police arrived to investigate. Even though I knew all the right answers to their inquiries, I still didn’t know the answer to the more pressing unspoken question: Why am I here?

The encounters in my neighborhood and the avoidance of open conversation at home trained me to keep to myself, ask fewer questions, listen more intently, and interpret others’ energy so I could adjust my own. I escaped into fantasy books and my own imagination, only to return to the reality of my own isolation and loneliness. The comedown amplified my impatience to be reunited with my dead family members. Perhaps, in their company on the other side, I’d feel like I belonged.

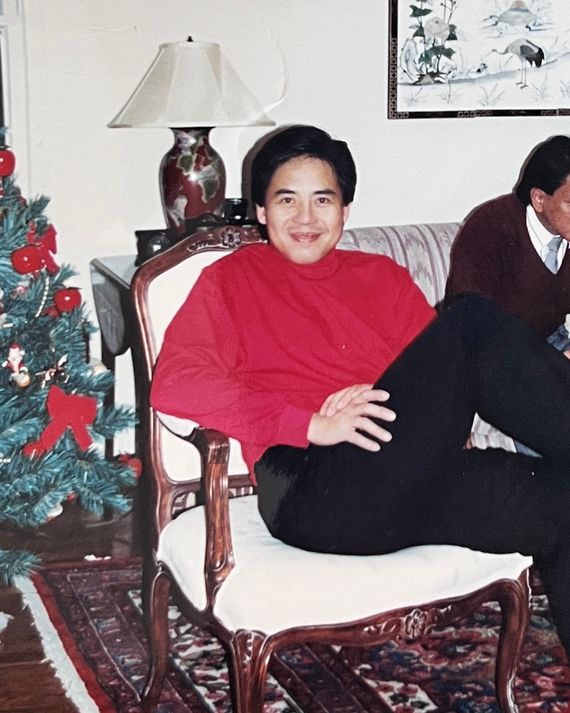

As I approached junior high, I became resigned to the fact that it would be a while before I escaped this earthly plane and, by extension, my insular suburban town. In my loneliest years, I was devoted to journaling multiple times a day, a practice that helped me realize my longing for death was actually a desire for connection. I slowly made more friends, went out more often, and started experimenting with fashion and makeup. In eighth grade, I chopped off almost all my chest-length black hair into a trendy pixie cut. I relished my friends’ shock. With every new look, my mother would shake her head and say, “You get your taste from your dad; he loved flashy things.” Eventually, in the years before and after I graduated from college in 2013, my focus shifted away from death and toward self-discovery.

That same year, I went on a trip to San Diego with my mom and my older sister Sasha. Somewhere between the zoo and our hotel, I fell asleep in the back seat of the rental car until a patch of uneven pavement shook me awake. My mom and Sasha were deep in conversation in the front, and even in my groggy state, I could tell the mood was strained. I don’t remember everything that was said, but a few things registered: My dad had died of AIDS, he was diagnosed while my mom was pregnant with me, and my mom waited almost 20 years to share the truth.

Back at the hotel, while my mom slept, Sasha tip-toed into my sofa-bed, whispering under the sheets like we did when we were kids, and confirmed everything I had overheard. The avoidance and secrecy from my mom, the passive aggression from my grandmother toward my father’s side — it all finally had a reason behind it. The next day, and for the rest of our trip, it was like that car-ride conversation never happened. We flew through a jam-packed itinerary, designed to maximize productivity and minimize any openings for conversation — just how Mom liked it. The facts of the matter had been shared, and a precedent had been set: No follow-up questions would be taken; no further discussions would be had.

After that trip, I took the lead in making a more conscious effort to celebrate my father’s birthday and death anniversary, a seemingly safe way to bring him back into the family conversation without actually discussing him. One year, Sasha and I decided to organize a small group of close family and friends to join the New York City AIDS Walk in honor of our dad, the facts of his diagnosis tersely tucked into an email about how to register and donate. As we gathered in front of Central Park, my sister’s childhood friend asked the question none of us dared to broach: “So, do you know how he contracted it?” Her mom quickly scolded her like she was still a child, insisting she shouldn’t ask. I looked at my mother she averted her eyes. A few minutes later, she tapped me on the shoulder. I looked at her expectantly as she leaned in and said, “You should tell everyone to head to the starting line.”

Despite being our only parent, my mother never seemed comfortable being in charge. She was often away from home, working herself ragged as a solo obstetrician and gynecologist to provide the best life for us. Whenever the house phone rang at 3 a.m., I would listen to her dutiful footsteps tread down the hall on her way to the hospital to catch the next newborn baby, wondering when in her busy schedule I’d see her again.

With her in a perpetual state of stress, I found ways, for both our sakes, to handle most things myself. I perfected my mom’s signature to sign off on permission slips for school and the occasional bad grade; I found the right times to sneak cash out of her wallet for things I wanted to buy, and any truly pressing questions were directed to my siblings and eventually the internet. Forgery, petty theft, and suspicious chat rooms felt preferable to agitating mom’s anxious energy.

Her fragile nerves had been made that way at a young age. The only child of my overprotective grandparents, my mother was shielded from boys and dating but not from the bullying that came with being the only Asian immigrant among her white schoolmates — an experience scarring enough that she never taught her children her native tongue for fear we’d be ridiculed for having an accent. Despite the schoolyard struggles, my grandparents made sure she was focused solely on her studies, dutifully following in their professional footsteps to become a doctor despite her aspirations to be the next Connie Chung.

What luck for her to have found my father, a fellow Filipino doctor whom my mother genuinely fell head over heels for. He was perfect on paper, so my grandparents gave their blessing to a whirlwind courtship, and they were engaged to wed after only a few months of dating. They were married for less than a year before my mother became pregnant with my brother and welcomed my sister and me (with aspirations for one more) before hitting their ten-year anniversary. The apparent perfection of their life together made it obvious to me how devastating my dad’s diagnosis and death must have been for her. Asking my mom to open up felt too cruel.

So over the decade that passed after San Diego, I followed my mom’s lead in avoiding the topic. Throughout my 20s, I was content to remain in my role as the youngest, obediently following my family’s commitment to dodging uncomfortable conversations and emotions. I left the holes in the story open and spent years quietly filling them with resentment instead.

When you say you don’t know how he contracted AIDS,” Fallon started cautiously, “do you have a fear around that?” I could sense Fallon’s question wasn’t her own, it came from my dad.

It was easy to connect the dots between the stigma of being a man diagnosed with AIDS in the early ’90s, the glare of the Catholic church, and the humiliation of being seen as outsiders yet again in a community my family desperately wanted to assimilate into. I wanted him to know that, though I was trying to understand what had happened between him, my mother, and my grandparents before I was born, I wasn’t interested in carrying their shame.

“If he contracted it from all the stereotypical things that people think, like drugs, or sex, or whatever, who am I to judge?” I replied. “I was born into an emotionally tumultuous energy but it’s separate from me. It’s not mine.”

“Beautiful,” said Fallon, smiling. “Your guides are saying that there is so much that lives underground and there’s very valid rational anger within you that wants to rip it up, pull the roots out from the system, and air it out,” she continued. “That’s a really big piece of your purpose here.” I didn’t know what to say. Fallon filled the silence for me: “You’re going to trigger people,” she said before laughing. “They’re saying, ‘She already has!’”

My siblings and cousins and I often joke about our immigrant parents’ expectations of us to follow the “right” path, as they did: a career in medicine or law; get married to someone they approve of; keep the faith; have kids. The punch line being none of those things resulted in happy endings for our parents. The day jobs didn’t match their daydreams, unrealistic expectations exhausted them, the marriages ended in death or divorce, and the kids were, well, seeing psychics instead of calling home. It’s not the dead that haunt us; it’s all the suppressed emotions that isolate each person from their true selves and, as a result, everyone around them.

“I see your dad as being a very creative person and having a lot of light to him, and there were many ways he felt like he couldn’t express that,” Fallon said. “I don’t know if that’s because he was a man or because he was supposed to be in the medical field, but there’s a way where his soul and his natural gifts were repressed.” Fallon paused for a moment before continuing: “Beauty. He loved beautiful things.” It was bittersweet to realize that what was repressed in his lifetime lived on in me. Every time I cut my hair, dyed it bold colors, or experimented with makeup, fashion, piercings, or tattoos, I knew it was a direct line to my dad.

Even though the shame of the generation before me wasn’t my own, it was still living through me. Self-expression and exploration were all well and good as long as I could prove I was also still embodying the traditional definitions of success. And other than my happy marriage, I had spent my 20s striking out on all fronts: an abandonment of the Catholic faith, a corporate career in media I burned out at, a deep fear of having children of my own. Despite my desire to eschew the path, I still felt the shame of failure, the fear of rejection, and a self-loathing guilt that the end of my dad’s life was the start of mine. It wasn’t until my recent search for spirituality, my decision to pursue a freelance career, and the realization of my own queer identity that I started to feel my shame turn to self-compassion. All of this was the key for me to start unpacking my hesitations around parenthood despite feeling called to it.

“Your ancestors lived with muted voices in their lifetimes, and they passed it down,” Fallon said. “It’s your journey in this lifetime to reclaim your voice for everybody that didn’t have the voice, and it’s not just healing for you; it’s healing for everyone on the other side. It’s healing for your dad.” She paused again, preparing to relay a message directly from my ancestors: “Where you can free the voice, you can free the soul.”

The full picture of these past few years of spiritual exploration, of feeling lost and lonely finally came into full view. My ancestors were calling me to heal our shared generational wounds, and the best place to start was healing all the unresolved pain around my father’s death and my birth. “There’s an ask of forgiveness from your dad,” Fallon said. I was stunned. I insisted there was nothing to forgive. But the earnestness in his ask made me realize what he really needed was acceptance — my acceptance. The same thing I sought from my grandmother, the family matriarch, during my first reading in Sedona. Did my father see me the way I saw my grandmother? As a leader of our family?

Of course he had my forgiveness, I told Fallon. And my love — it was unconditional. “He’s saying that you gave him something he had been needing today,” Fallon confirmed. I hoped I could do the same for my mother.

The day after meeting with Fallon, I sat down with my mother at the dinner table she and my father had bought together to live their life around. She was mindlessly thumbing through the heaps of her unsorted mail when I started to tell her about my reading. “Oh, you know, I don’t believe in all of that,” she said, not looking up from the pile of envelopes and catalogues. Reining in my impulse to snap at her dismissiveness, I told her I had connected with Dad, that I could feel his shame, and that Fallon sensed she and my father had separated, which I couldn’t confirm. As far as I knew, they were together until his end.

She finally looked up at me, her hands slowly letting the letters fall to the table, the smooth skin around her temples tensing. “I was planning to die with this secret,” she said, her shoulders hunching inward as she crossed her arms over her chest.

As she spoke, her words played out like an old movie in my mind. Though I hadn’t seen any of these memories unfold, I had felt every moment as she carried me in her womb. My mother’s confusion when my dad couldn’t catch his breath while they were on a flight home from a medical conference. Her distress when the flight attendants dropped the oxygen masks just for him. Her terror as a medical team deboarded him straight to the hospital, where he remained in a coma while they ran every test they could.

It was as if I were standing in her office when she got the phone call from the hospital, my father’s diagnosis catapulting her into a spiral of shrieks and sobs. I could see her as she collapsed at her desk, clutching at me in her womb through her distended belly as she screamed into the phone: “My baby! What about my baby?”

It had never occurred to me that the truth wasn’t just a source of anger for her, but of panic and terror for both our lives. I silently thanked the universe that my mother and I are both healthy. I could feel my body playing catch-up, my breath quickening, my heartbeat racing: a sudden release of the unforgotten biological reactions to my mother’s stress I had experienced in utero.

While she gave voice to her most traumatic experience, I envisioned my normally impassive mother in a jealous rage as she tore through their bedroom and discovered letters among my father’s things that confirmed a previous romantic relationship with a man.

At this point, my father was still incapacitated in the ICU, unable to address any of her questions, comfort her despair, or soothe her rage. In the absence of answers, her mind went to the worst assumptions: Had he been unfaithful or was this all in the past? He was a gay man; their relationship was a fraud; he never truly loved her; their whole life together was a lie.

When he finally regained consciousness, his reaction to the discovered letters was all my mother needed: “He just bowed his head. He couldn’t even look at me.” He also couldn’t convince her that he had never been unfaithful; that being with a man in the past didn’t mean his love for her wasn’t true; that everything they had built together, their home, their family, was real. Her heart was sealed shut, and it remained that way until he died three years later.

As her story came to an end, her arms were still folded as she stared down at the table. I could sense the slightest drop in her shoulders, a release of tension in her face that signaled a sense of relief. I could feel any bitterness of my own toward her being replaced with sympathy and love. If I could forgive my father so easily, how could I not give the same unconditional love to her? “Mom,” I said gently, “there’s a reality where he had this other side to himself and also loved you. Both things can be true.” She nodded silently. “And why did you feel like you had to take that to your grave?” I asked, this time letting my exasperation slip through. She agreed that it had been hard and said that she had never gone to therapy, never talked to anyone about what had happened or how she felt. “Now you can talk to me,” I said.

I stood up from the table feeling drained but relieved that I only needed to take a few steps from the table to the bedroom off the kitchen where my grandmother lived out her last years. Now it was my room. Almost exactly a year prior, my husband and I had decided to move back to my childhood home to save both money and my relationship with my mother.

The next morning at dusk, I walked from the house to the same nearby rocky beach I grew up going to. As I sat down to watch the sun rise, my whole body shook as I started to sob. Each exhale felt like I was lifting the invisible weight I had always carried off my back. When I wiped my tears, it was like I was tenderly clearing someone else’s face. I didn’t understand how I could feel so vulnerable but also so strong.

At that point, I didn’t know that my first child had already started growing inside me. I didn’t know that I was healing my family’s past while creating my family’s future. But I finally knew why I was here.

More From This Series

- Why Is Sleep Paralysis So Terrifying?

- Ghost Hunting at Wall Street’s Most Haunted Bar

- When Your Ex Comes Back to Haunt You