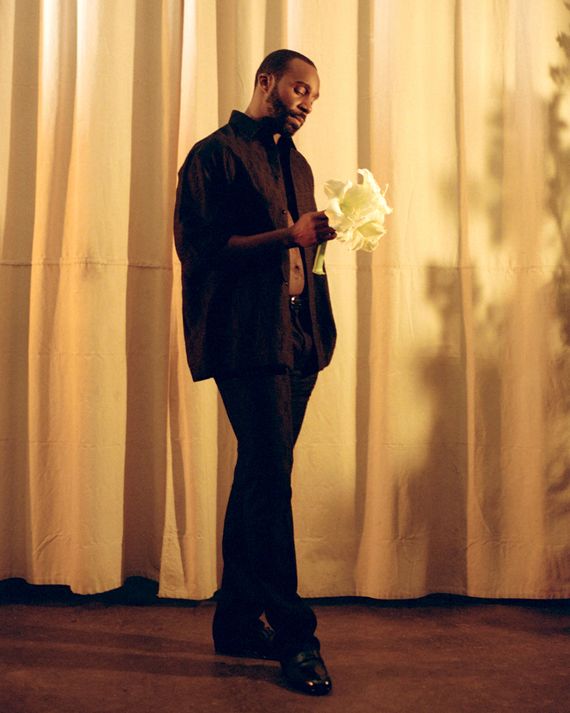

Tramell Tillman and I are lost. Figuratively, in conversation, but literally, in the winding paths of the New York Botanical Garden, where the Severance actor manages to cut a figure both sharp and smooth. He’s dressed in a suede-and-shearling coat in a warm, deep brown, reminiscent of marshmallows melting into hot chocolate; a matching brown beanie; and a festive green-and-red scarf in a wide plaid pattern tied cozily over a butter-yellow sweater. This upper-body party is paired with a simple pair of light-wash blue jeans and clean but perfectly worn-in white Gilbert Crockett low-top Vans, their emerald-green stripes tying it all together. When we spot a large, stately building with a column-lined entrance, the gentlemanly actor holds the door for me before confidently approaching a lone security guard to ask for directions to the garden’s conservatory.

As we walk, Tillman tells me he has always loved flowers. “Don’t laugh, but they represent, to me, the best part of our humanity,” he says. “They blossom and bloom without overshadowing anyone else. And when their time is up, they’re done.” Flowers are miraculous, we agree. I patter on unintelligibly about how it is that these plants come to be, and he verbally sweeps me right off my feet. “I think it’s the violets that grow and blossom in the most extreme conditions,” he muses, proceeding to quote from Tennessee Williams’s Camino Real: “‘The violets in the mountains have broken the rocks.’ It’s beautiful that something so delicate can pierce through something hard and rough. You don’t expect that. It’s defiant.”

Tillman grew up in suburban Maryland, near his birthplace of Washington, D.C. Prince George’s County was, at the time, the wealthiest majority-Black county in the United States (it was recently surpassed by neighboring Charles County). Lofty ambitions were not just accepted but expected in his community — as long as you were a doctor, lawyer, administrator, or business executive. His first acting gig was sort of an accident; his mother volunteered to play a role in their church’s Christmas play, and they needed someone young to play her son. Ten-year-old Tillman was a shoo-in for the part. “I didn’t want to do it,” he remembers. “I’m pretty sure I cried backstage before going on because I was so shy. I didn’t like attention. I’m still kind of that way.”

He was exhilarated, and as he pursued acting more seriously, he found performing could be an outlet for processing his real-life experiences and emotions. On Severance, Tillman’s portrayal of Seth Milchick feels personal. The series follows the employees at Lumon, a mysterious corporation, where they have undergone a procedure, severance, to separate their work selves (“Innies”) from their outer selves (“Outies”). It is a mystery-box show, in which questions unspool into more questions. Milchick is one of the non-severed employees working on the “severed” floor, and his job is to keep the severed employees in line and at least moderately content; he plans sterile, corporate birthday parties and doles out tedious punishments for misbehavior. For the majority of the first season, Milchick is polite, firm, and nonreactive — the platonic ideal of a company man. Tillman plays the character as totally self-possessed — levelheaded, efficient, ready to face any challenge. It’s not often that Milchick’s carefully buffed veneer cracks, but when it does, he reveals a frightening ferocity.

There are brief moments in the Apple TV+ show’s second season in which Milchick’s loneliness as one of the few people of color in charge reveals itself, and unexpected settings and situations slowly peel back some of his vulnerabilities. In one interview, the actor compared the character to an iceberg: a calm physical presence with a whole unseen world going on underneath the surface. This season, Tillman says, the waterline is a little lower. The character’s vulnerability particularly comes into focus when Milchick faces a sterile, corporate gesture — one that serves as a painful reminder of his difference from the other employees at Lumon. “No one else in this cast so far has been othered based on race, so now it takes a whole different tenor,” he says. “How do we go about it without alienating people and also bring humanity to it and allow it to be true and not distract?” Tillman says he discussed this moment extensively with series creator Dan Erickson and director Ben Stiller, advocating for an honest depiction of how Milchick might feel. “I didn’t ever want to play a character in this world that was not aware of their racial makeup,” he says. “We had to really be careful how we stepped through in telling this story. ”

Tillman doesn’t have to imagine what it’s like to be one of the few Black employees at work — he was the only Black student in his acting M.F.A. program at University of Tennessee Knoxville. It was a culture shock, since he’d previously studied medicine at Xavier University in New Orleans, an HBCU, and received a communications degree from Jackson State, also an HBCU, for undergrad. He worked for a few years before starting at UTK, including with the CDF’s Freedom Schools project supporting children affected by Hurricane Katrina. “I stood out like a sore thumb, and although my classmates were always supportive and my teachers were supportive, it was the environment outside of the theater that was toxic,” Tillman says. “I was fortunate to have the work to help me push through it.”

Tillman spots some model trains chugging along the tracks decorated for the holidays outside of the conservatory. He’s tickled and a little nostalgic. “I used to love trains as a kid,” he tells me. “My dad used to work for Amtrak, and we’d take the train everywhere.” He had a model train set of his own and loved flipping the switch and watching it spout real steam. In his youth, he tells me over the sound of tiny train whistles, he had a very specific vision for what his life would look like: He would go to Meharry Medical College, move to Atlanta, marry a woman, and have six kids. “I had names,” he says.

In college, along with letting go of his future as an orthopedic surgeon, Tillman also started to loosen his grip on the idea that he was straight. He began exploring his sexuality, dating both men and women for a time. “I had to do it silently,” he remembers. It didn’t feel like there was space for him to explore openly, and he’d grown up in the Baptist church, where anything other than heterosexuality wasn’t an option. “I just started to question it the more my world opened up,” he says. The world he lives in now is one that he would have had a hard time picturing back then.

Since 2014, he’s been living in New York, hustling at times between auditions and holding down multiple jobs. He had a quick stint in Los Angeles around 2017, where he aimed to focus more on TV and film, before returning back East in 2018 to play a gay coffee-shop owner on the short-lived series Dietland. A year later, he appeared on Broadway as activist Bob Moses in The Great Society. He also started to think more about his love life and his identity relating to it. “I remember going through a list,” he tells me. “I looked up the top 100 gay men in the industry. The majority of them were white.”

He worried that coming out publicly as gay would affect which roles would be available to him. “I had this knock on my heart saying, ‘Tramell, you have a choice.’” As he saw it, there were three paths. He could get a beard and play straight for the rest of his life; stay permanently single and keep his sexuality a mystery; or he could just be open. One night, he dreamt that he was onstage, and just off to the side was a man holding a baby. He didn’t recognize either of them, but he knew that the man was supposed to be his husband and the baby was their child. He woke up in tears, resolving to live as his authentic self.

Tillman is comfortable with his sexuality now. He even came to these same botanical gardens last year for a date: “It was like a Hallmark holiday fairy tale,” he remembers. Still, anyone trying the apps in New York City, regardless of their orientation, wouldn’t say it’s a breeze. Having seen the biceps currently hidden beneath his suede jacket on TV, and having spent the afternoon with an up-close view of his radiant smile and kind eyes, it’s difficult for me to believe that the man in front of me has ever even minimally struggled in the romance department, but it turns out his problem is one I can relate to: He’s a total romantic in a city of commitment-phobic cynics. His ideal first date? An open house. Partly, it’s his inner HGTV fan coming out. It can also tell you a lot about the person you’re trying to date, Tillman says. “You can also learn how they navigate awkward situations,” he tells me. “Most people just want to go to the bar, and there’s nothing wrong with that. But I’m five years sober, so there’s only so many ginger ales I can have before it gets old.”

At the moment, Tillman isn’t dating at all. He’s busy wrapping up a two-month run of Slave Play director Robert O’Hara’s latest, Shit.Meet.Fan., at the MCC Theater, and preparing for the world to see him on the big screen in Dead Reckoning, the eighth installment of the Mission: Impossible franchise, this spring. He has, however, been reflecting on exactly what it is that he’s looking for in a relationship. “Now I know what I want,” he says. “I’m old-school. It’s harder for people to want to court now. I’m loyal; when I find somebody and I ride with you, I am with you. I think it’s a beautiful way to have a relationship, but it’s not the most popular way right now.”

The sky has darkened slightly, the wind has picked up, and we’ve been roaming around the outdoor train display long enough to numb our sneakered toes. We head inside the conservatory, which is decorated with plants and even more model trains traveling around tiny replicas of the New York Public Library and Radio City Music Hall, constructed entirely of materials found in nature — rocks, sticks, leaves, seeds, bark — and doused in thick coatings of varnish to preserve them. We’re ambling along, trying to stay out of the way of the crowds of visitors. Our pace slows as our focus shifts to admiration of the plants and the décor. Organically, I learn more about Tillman in our final moments together: He has eight houseplants and no pets; his favorite color is blue; he can’t do Kindle reading and needs physical pages of Colson Whitehead, Nikki Giovanni, and James Baldwin to turn; his favorite Christmas movies are all classics, The Miracle on 34th Street and How the Grinch Stole Christmas and Home Alone.

We pass through more sections of the conservatory: the “rainforest” and then the “desert.” Walking through a metal tunnel, we agree that if this were a Mission Impossible movie, we’d be running from an explosion right now. On the cusp of a new season of Severance, MI: Dead Reckoning, and his 40th birthday in June, Tillman is looking forward to the year ahead, but it’s hard to have a plan when his life has already surpassed his wildest dreams. “As a kid, I didn’t really feel like I had a voice,” Tillman says. “I was often told, by many different sources, that what I endured was not real. I was often left to figure out my life or my struggles by myself. And while I had people that loved me, there was a lot of self-isolation.” Now that he has an audience, he’s intentional with how he communicates with them, and he’s hoping to get into directing, producing, and maybe even spending more time on Broadway. His strength is in his ability to focus. “I think a lot of it has to do with listening to myself, keeping out the distractions and not allowing people to tell me what I can and cannot do and can and cannot enjoy,” he says. “Just following my bliss.”