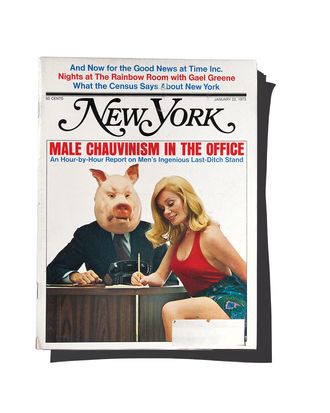

Certainly it was odd for a guy to be assigned to write “Male Chauvinism in the Office: An Hour-by-Hour Report on Men’s Ingenious Last-Ditch Stand.” It is a world-beating piece of mansplaining, to use a word that did not exist in 1973. But at the time, the idea was at least sensible: an inside report from a corporate setting by a fairly enlightened executive. Michael Korda was a publishing golden boy, a few years into a four-decade run as the editor-in-chief of Simon & Schuster.

Much of his story is concerned with the first-generation revolt against the casual sexism of the workplace, and the old hierarchy that’s been knocked for a loop. “Coffee is a great source of conflict,” he writes. “Women’s liberation has brought to an end the old-fashioned coffee pool, in which women more or less voluntarily grouped together to keep a percolator going … and in any office its demise is the first warning signal that women are beginning to think about their roles.”

Korda describes a divide between the secretary track (where most women would remain) and the management track (where men’s careers were open-ended), and tells of a woman whose job is to break in the young guys, who then become her bosses: Among other things, she “show[s] him how to make out the expense account she doesn’t have.”

The Office Now

Today, few entry-level professional positions are so blatantly gender-specific — it probably helps that barely anyone merits a secretary anymore. Still, deep in the story, Korda quotes a more persistent trend: In 1973, women professional workers were paid 66 cents for every dollar a man made. The current figure is 79 cents, which isn’t that much better. And that’s despite the fact that nowadays, men and women hold professional-level jobs at the same rate, and at about the same pay. A Pew Research Center study in 2013 found the pay gap for millennial women to be smaller, 93 cents on the dollar, and a recent study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York pegged the difference between young men and women’s pay at just three cents.

That gap widens as workers age, and really takes off after age 30. By their late 30s and early 40s — prime child-rearing years — men are earning an average of 15 percent more than women. Several studies have explicitly linked the pay gap for mid-career workers to having children, including one from Michelle J. Budig, a sociologist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, who found that fathers actually see a pay bump.

In Korda’s story, the few women who make it to the executive level have to work harder and longer than their male colleagues to prove themselves. Childbearing, meanwhile, is considered nearly disqualifying to a woman trying to rise through the corporate culture. Korda quotes Lois Gould, an author who’d worked at Look magazine, who had to fight her employers to stay past her sixth month of pregnancy. “They didn’t even want to look at me for fear I’d miscarry right there,” she says of her bosses. “In the end I had to produce a weekly note from my doctor saying that I was not about to give birth on the premises. They wanted me to drop out without pay, and I wouldn’t.”

Now that 71 percent of women with children work, a story like Gould’s would be unthinkable. And yet, we’re still in the process of remaking office life to account for all those ambitious women. It wasn’t until 1993 that new mothers who took leave had any guaranteed job protection, and only five states require any paid parental leave, including New York, which just passed a paid-leave act this year. Four decades after Korda’s story, how to accommodate women in the workplace is a campaign issue, which is both progress and not.

“Communications have broken down,” Korda writes. “Men have become aware of women’s protests and even sensitive to them without really coming to grips with the substance of women’s demands or making an honest effort to change the way things are.” He, you will not be surprised to learn, came out okay: This New York story became his first book, Male Chauvinism! How It Works, and he continued to run Simon & Schuster, powerful and very well liked, until he retired in 2005. S&S’s current editor-in-chief is a single mother by the name of Marysue Rucci. Her job duties do not include making coffee.

*This article appears in the May 16, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.