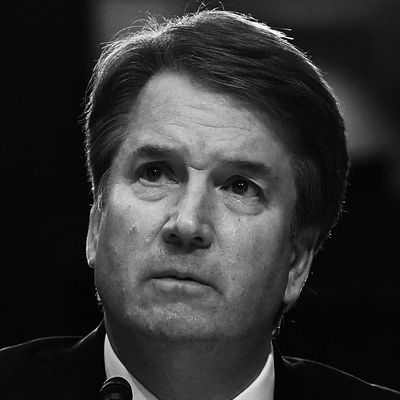

Leaked emails today from Brett Kavanaugh’s time in the Bush White House reveal what everyone already knew: that Trump’s SCOTUS nominee will pose a threat to Roe v. Wade. To get Maine senator Susan Collins’s vote, Kavanaugh called Roe v. Wade “settled precedent,” but according to an email he wrote in 2003, “the Court can always overrule its precedent.” In other words, though Kavanaugh recognizes that the Court has repeatedly found a right to abortion, he knows he can use his power as a justice to change that.

Is Kavanaugh willing to make abortion illegal or impossible? We don’t need emails to know. He wouldn’t be at his third day of confirmation hearings if the Trump administration didn’t think so; to get there, Kavanaugh had to send early signals to them to prove himself. He’s already said everything they — and we — need to know about where he stands.

The timeline tells a story. During his campaign, Trump promised with unprecedented bluntness to appoint judges who would overturn Roe “automatically.” In consultation with legal elites who had decided they could make their peace with him in exchange for legions of lifetime judicial appointments, Trump took the unprecedented step of releasing a series of lists of names to prove he was serious about naming the conservative movement’s legal soldiers and not, say, Jeanine Pirro or his sister to the courts.

Kavanaugh wasn’t on the first list, in May 2016. He wasn’t on the second, in September 2016. Two things happened before Kavanaugh passed muster, as Connecticut senator Richard Blumenthal highlighted in his questioning yesterday.

In October 2016, Kavanaugh recalled yesterday at his hearing, “I was driving home on a Wednesday night, as I recall, and the clerk’s office called and said we have an emergency abortion case, which is very unusual in our court. First time I’d had one.”

Before the D.C. Circuit was the case of Jane Doe. “She was a 17-year-old unaccompanied minor who came across this border having escaped serious, threatening, horrific physical violence in her family, in her homeland,” Blumenthal said yesterday. “She braved horrific threats of rape and sexual exploitation as she crossed the border. She was eight weeks pregnant. Under Texas law she received an order that entitled her to an abortion. She also went through mandatory counseling as required by Texas law. She was eligible for an abortion under that law. The Trump administration blocked her.”

Being asked to rule on whether Jane Doe could get an abortion had to be a nervous-making experience for Kavanaugh, who has long been groomed for the highest court. As he knew from his involvement in getting George W. Bush’s judicial nominees confirmed, paper trails on abortion are a tricky thing. Say too much, and you can’t get through, not when you need the votes of senators who know Roe v. Wade is popular (in today’s math, ones like Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski). Say too little and you won’t get nominated at all, not when the right is still bitter about Republican-nominated defectors like David Souter, Sandra Day O’Connor, and Anthony Kennedy, who upheld the right to abortion.

Kavanaugh’s response was to try to kick the can down the road. He and one other judge on the panel, professing concern for Jane Doe, suggested instead that Jane could get her abortion, but first she had to wait even more time for the government to find a sponsor — a qualified adult. This sounded reasonable, except Jane had already proven to a judge that she was mature enough to make her decision and had undergone Texas’s required counseling and ultrasound.

But it was a hollow solution, as Judge Patricia Millett pointed out when the full court overruled Kavanaugh and said Jane could get her abortion: The government hadn’t approved any sponsor in the seven weeks since Jane had asked for an abortion, and she would soon be past Texas’s 20-week abortion limit. “A nine-week waiting period before litigation can start or resume, if adopted by a State, would plainly be unconstitutional,” Millett said. In the meantime, the risks to Jane Doe’s health, physical and emotional, increased weekly.

In the end, Kavanaugh didn’t manage to stop Jane Doe, but he accomplished other things in that opinion. For one thing, he didn’t assert that Jane had a constitutional right to abortion. For another, as Blumenthal pointed out, he larded his opinion with code words like “abortion on demand” and referred to “existing Supreme Court precedent” and how lower courts, at least, had to abide by it. The wording, Blumenthal remarked yesterday, is “a little bit like somebody introducing his wife to you as my current wife. You might not expect that wife to be around for all that long.”

Then Blumenthal got to the point: “Let’s be very blunt here. [Your opinion] was a signal to the Federalist Society and the Heritage Foundation and to the preparers of those lists — the president outsourced that task to those groups — that you were prepared, and you are, to overturn Roe v. Wade.”

Blumenthal didn’t mention it yesterday, but there was another signal Kavanaugh sent just one month before the Jane Doe hearings. He gave a speech at the conservative American Enterprise Institute praising his “first judicial hero,” former Chief Justice William Rehnquist, who dissented in Roe v. Wade. “For 33 years, Rehnquist righted the ship of constitutional jurisprudence,” Kavanaugh said.

That was September 2017. Jane Doe was October 2017. In November 2017, Brett Kavanaugh was added to Trump’s Supreme Court list.

Kavanaugh also gave himself away on Wednesday when he discussed his reasoning in the Jane Doe case.

“I was trying to follow precedent for the Supreme Court on parental consent,” Kavanaugh said yesterday, “which allows some delays in the abortion procedure so as to fulfill the parental consent requirements.” The Supreme Court has previously said that states can require minors to get the permission of their parents, as long as they have the option to go before a judge to bypass the requirement without major delay.

But Jane Doe had already done that. Kavanaugh had invented a new theory that because the Supreme Court says that some minor delays are allowed, any delay is too. For all the Republican talk this week of judges not legislating from the bench, Kavanaugh’s gambit looked a lot like making it up as he went along. So far, it’s worked for him. But it leaves little doubt what a Justice Kavanaugh would do.