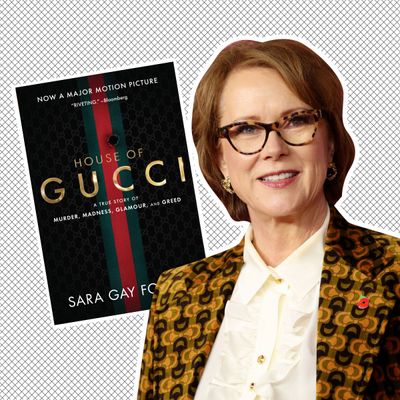

For all of 2021, we’ve been anticipating the release of Ridley Scott’s House of Gucci. The second those gorgeously strange photos from set started trickling out, it was clear the movie was going to be huge — a Zeitgeisty perfect marriage of true crime and camp. And then when the trailer finally dropped, the excitement was explosive. It was further confirmation that HOG was a must-see; every detail of it was impeccable, from Jared Leto calling a pink corduroy suit “chic-ah” (he’s not wrong), to Adam Driver looking glamorous in huge glasses and huge sweaters, to the way Lady Gaga says “but I am fer” and murderously taps her little espresso spoon. But long before the public started obsessing over the Gucci family story, journalist Sara Gay Forden was literally writing the book on it. Scott’s script is based on Forden’s book of the same name, first published in 2000.

Forden’s book, which centers on the story of Maurizio Gucci’s murder but also tells the company’s complete history, starting with its founder Guccio Gucci, has surged back onto the New York Times Best Sellers list. The renewed interest in the story has been a chance for Forden to reflect on the events she meticulously narrated 20 years ago and to see the story from a new lens: that of a viewer. The Cut spoke to her about how a family business turned murderous and what it was like to tell the Gucci story.

What attracted you to the Gucci story?

I think it was Maurizio. He was delighted, but he was also determined. The force of his desire to revive Gucci was very infectious. He spread it to people. And then the tragedy of him not being able to do it — I found that compelling, and I wanted to cement his legacy because I felt that he was going to be forgotten. He was spending all this money and he was running the company to the ground, but he had a longer-term vision, and he probably miscalculated how willing his Investcorp partners were in bankrolling him. At the end, he said, “Give me just six months and I promise you, the wind will be back in our sails.” And they didn’t give him six months; they forced him out well before that. Sure enough, six months later, sales were through the roof. It took a while to complete the turnaround, but he was right.

Your book has become sort of the definitive telling of Gucci’s history. Did you feel the weight of that when you were writing it?

Well, I didn’t feel the weight of that because I couldn’t have imagined it, but I did feel it was a really daunting enterprise and I felt very small. I was uncertain about whether this book was going to be successful. At one point, I had reached out to Severin Wunderman, the watch manufacturer whose licensing of Gucci watches was always extraordinarily successful. The fees from the licensing kept the company afloat. I asked if he would talk to me, and he called me on my Motorola Brick cell phone when I was in the courtroom — the trial had started. He said, “I’m going to write the Gucci book. I knew Aldo, and I know everything about the story. I’m a very wealthy man, and I’m going to make the movie and your book is going to be nothing.” I was literally shaking in my boots.

I interviewed people all around the watch license, and I distilled it into three pages. In those days, it was still fax, so I slipped the three pages into the fax machine with a cover letter and I said, “Dear Mr. Wunderman, I know you didn’t want to be interviewed for the book, but I’ve done this work. It would mean a lot to me if you would read these pages and tell me if there’s anything wildly inaccurate or if there’s anything you want to add.” And I’d just fed the last page into the fax machine and my phone rings and it’s him. And he says, “Miss Forden, it’s Severin Wunderman. You have two choices: next weekend at my chateau in the south of France or the weekend after in my townhouse in London.”

Oh, wow. So you got the interview.

I was a single mom with a 3-year-old, so I couldn’t go to a chateau in the south of France, but I went to London. I think I must have spent five or six hours with him. He was an incredible person. I could have written a whole other book on Severin.

I was impressed by how intensive your interviewing process must have been. The descriptive and scenic language is so detailed. I was like, How does she know this?

In each interview, I would try to cull a few details that I could add to my scenes. Everybody had a different perspective, and everybody was at odds. I had to do a lot of work to rationalize all these different viewpoints by sifting through all my research to try to find out what was the closest to the truth. I hadn’t read it for 20 years myself, and I went back and read it this year. I was saying, Hold on, like, How did I know that? I’d forgotten a lot. A lot of it was making connections between things that different people said. And once the trial started, I was in court pretty much every day. I wanted to make sure I captured the key moments and I could see the expressions on people’s faces and hear what they said.

You clearly gave Ridley Scott rich material to pull from. What did you think of the movie?

It’s extraordinary. I was passionate about writing the book, it took two years of my life — it was really a lot of blood, sweat, and tears. They’ve taken an already compelling story and they’ve really kicked it up several levels.

Yeah, I was curious what you thought about the casting — I know some people from the Gucci family reacted negatively to it.

I mean, first of all, Lady Gaga was perfect for Patrizia. She’s Italian. She’s short and petite, like Patrizia was. She’s mighty in her personality. She’s sexy. She’s got style. And even though the press at the time dubbed her the Vedova Nera — the Black Widow — she has a compelling story too.

She does — there was so much focus on her obsession with money and luxury, but there’s more to the story than that. When this book was published, there wasn’t much questioning of capitalism in the mainstream political discourse in the U.S., and now there’s a much more vocal anti-capitalist movement. Do you think the movie and the book approach questions of class and privilege differently?

That actually influenced my sort of disenamorment with the luxury industry at the time. Those companies were just raking in the money, they were so profitable. And yet I didn’t see a big push toward sustainability or giving back. The movie focuses pretty specifically on the family dynamics and the relationship between Patrizia and Maurizio, and it ends before the whole turnaround of Gucci. I think the class issue was evident in that Patrizia came from humble beginnings, and she was considered kind of an “other side of the tracks” woman in Milanese society.

One of the things I tried to explain in the book is that Italian society is very stratified. There’s this whole concept of bella figura, keeping up appearances. They didn’t mix social classes. That’s why Rodolfo was outraged when Maurizio said he wanted to marry Patrizia, because he saw her as a social climber and a gold digger. I think she never felt safe or welcome in that very closed society. That’s one of the elements that we have to consider when we try to understand, you know, how she evolved and what she did.

Do you have any empathy for her?

While we can’t condone what Patrizia did, we can be empathetic about what it must have been like to find herself catapulted into the middle of this very dysfunctional family. And then to have lost what she had acquired with no resources of her own, since she came from modest beginnings. She had aspired to that world, but then she didn’t really know how to come down off of it. There just was a sense of fewer options, especially for a woman. It was a very patriarchal company and a very patriarchal society.

Patrizia is now out of prison. Has she ever reached out to you or anything like that?

I actually tried to interview her when I was in Milan in September, but she’s now under the supervision of a court-appointed administrator and they aren’t allowing her to do any interviews. I interviewed her in person in 1993 in her Milan penthouse apartment shortly before Maurizio lost control of the company. She had launched a smear campaign against him in the media and was reaching out to journalists and was giving interviews disparaging him. By the time I started writing the book, she was in jail and the prison authorities declined my requests to interview her. I did start a jailhouse correspondence with her, in which she shared what her early years with Maurizio were like. At that time, she was still maintaining her innocence.

I can’t imagine what it was like to be working at Gucci when all this was happening. Especially considering how intimately connected people were with the work that they were doing.

There are ex-Gucci people all around the world who are kind of in touch still.

Like they’ve all gone through this significant thing together, and they’re all still connected by it.

Exactly.

Do you feel part of that?

I do. I am part of it. As a journalist writing the book, I was a little bit at a distance; it was more observing and trying to keep perspective. But it drew me in too, and now it’s drawing me in in a different way where I’m not the writer anymore, I’m the participant. Or maybe I’m the narrator.