On September 19, 2017, as Hurricane Maria ravaged Puerto Rico, curator Marcela Guerrero was in New York City taking care of her newborn daughter. Like millions of Puerto Ricans in the diaspora, Guerrero, who had started her role as assistant curator at the Whitney Museum just five months before, waited for updates from her family back home. In the days, weeks, months ahead, the cruel truth made its way across the Atlantic: The Puerto Rico Guerrero left in the early 2000s would no longer be the same. In the meantime, Guerrero was already plotting how to help. I could make donations and I could volunteer, she thought, but if I was going to use my platform to make a difference, how could I do that?

“No existe un mundo poshuracán,” the largest survey of Puerto Rican art inside a major American museum in 50 years, opens to the public at the Whitney Museum of American Art on November 23. (Member previews begin today.) The multi-artist exhibition, which includes works from 20 creators based in Puerto Rico and within the diaspora, confronts so much more than the physical destruction of the hurricane, weaving in the political upheaval and collective trauma left behind in the aftermath. Visitors will walk through separate sections highlighting the major consequences of Hurricane Maria: fractured infrastructures; resistance and protest; ecological devastation; the impact of tourism; and grief and reflection.

“Hurricane Maria marks a before and after for Puerto Ricans,” Guerrero tells me over the phone, letting out a heavy sigh before she continues. The death toll from Hurricane Maria, which journalists and activists had to urge the government to audit, was nearly 5,000, according to a Harvard study. The lack of power, water, and reliable infrastructure ushered thousands to leave their homeland to the so-called “mainland,” depleting the archipelago’s population even further. The U.S. Congress–appointed fiscal board — a result of the Obama administration’s passing of the PROMESA bill — has continued to enact austerity measures, leading to school closures and pension cuts, to get Puerto Rico out of its crushing debt. Living precariously as a result of these measures, Puerto Ricans have often poured out into the streets in protest demonstrations, including the 12-day stint that led to the resignation of former governor Ricardo Rosselló and recent mobilizations calling for the government to cancel its contract with the American power company Luma Energy.

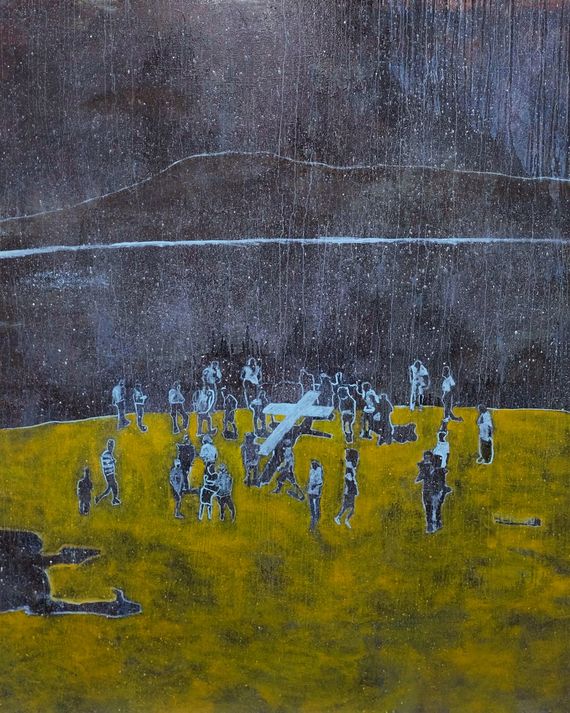

“The counterresponse to all of that is coming from visual discourses,” says Guerrero of how Puerto Rican artists have reacted and resisted through their work, some of which is featured in the exhibition. “It’s a super-powerful tool.” Take, for example, a painting by Rogelio Báez Vega that encapsulates the desolate infrastructures left behind by school closures, or the photograph Untitled (Valora tu mentira americana), by Gabriella Torres-Ferrer, which shows a hurricane-ravaged electric post bearing a pro-statehood poster urging Puerto Ricans to “value your American citizenship.” There is also Sofía Gallisá Muriente’s B-Roll, a video collage that deals with the promotional footage presented to foreign investors and tourists by the Puerto Rico Tourism Company and other local organizations, highlighting its colonial undertones. And, of course, a copy of the poetry book While They Sleep (Under the Bed Is Another Country), by Raquel Salas Rivera, a harrowing work that confronts the United States with its present colonial reality that includes a line that inspired the exhibition’s title.

Some of the most poignant pieces in the exhibition come from Carolina-based artist Gabriella Báez, whose work explores grief in the aftermath of her father’s suicide ten months after Hurricane Maria. “I am 100 percent convinced that my father’s death was a consequence of the hurricane’s aftermath,” Báez tells me. “If the [government’s] response had been effective, if we had access to basic resources, my dad would be alive today.” (Following Hurricane Maria, suicide rates in Puerto Rico spiked by more than 50 percent, according to a report by the local health department.) With three pieces inside “no existe un mundo poshuracán,” Báez explores grief through exhibiting her father’s objects — family photo albums, a Pink Floyd T-shirt, old notebooks — as a way to “explore the complexities of memory.”

Through studio visits and conversations with artists and academics, Guerrero spent the last five years absorbing the social and political landscape in Puerto Rico. But curating “no existe un mundo poshuracán” also required her to look inward. “This is definitely the most personal project I’ve ever done and perhaps will ever do,” says Guerrero, her tone conveying this bittersweet moment: a major professional milestone that weighs heavy with sorrow for what’s happening in her homeland. “And I think that’s transmitted in the exhibition.”

The process also forced Guerrero to ask herself uncomfortable questions about what her presence inside an institution like the Whitney Museum symbolized, not just for Latinx-made art, but for Puerto Rico. During our conversation, she referenced the 2015 Mellon Foundation survey that revealed that only 3 percent of museum curators, leaders, and educators were Hispanic, which ushered in a wave of multicultural talent inside these institutions. Like many people of color and cultural minorities inside predominantly white spaces, her job has carried more weight than she ever asked for: “I always keep in mind that my role as a curator means something bigger in the larger context, that my identity comes through in my curatorship.” And Hurricane Maria inflamed that feeling. “I am very proud to be Puerto Rican, to have a bilingual brain, even if I feel like an outsider,” she says. “So many other people have had the option to focus on white artists throughout their careers and no one criticizes them.”

Guerrero is redefining what we consider “American art” through featuring Puerto Rican artists molded by the American experience yet denied basic American rights like the ability to vote for the president of the United States. In “no existe un mundo poshuracán,” the realities of the United States’ rampant colonial policies are exposed — or, as we say in Puerto Rico, a flor de piel — inside one of the country’s most prestigious cultural institutions. This work belongs inside a place with the words “American Art” on the sign outside. The best display of American art is one that’s colored with the trauma of second-class citizens inflicted by the very country that calls itself “land of the free.” Of course, not everyone will agree. But Guerrero has little care for whom she might upset with this act of artistic rebellion. “There will be people who will not agree [with the exhibition],” she says. “But the benefits outweigh the risks.”

Because there will be others who will walk into the expansive gallery on the museum’s third floor overlooking the Hudson River, past the Rothkos and O’Keeffes, and see through Puerto Ricans’ eyes. Like the third-generation Nuyorican who will feel a call to bridge the gap with their ancestors’ homeland as they walk around the space. The European tourist who remembers reading a New York Times story on the death toll of Hurricane Maria and steps inside curious to learn more about how Puerto Rico is faring today. Perhaps even the museumgoer who has never heard of Puerto Rico or Hurricane Maria and unexpectedly sees for themselves just how detrimental it is to exist in the shadow of the richest country in the world. “Colonialism is still very present and Puerto Rico is evidence of that,” Báez says. “So I hope people come out informed of how colonialism is embedded in everything that’s happening in Puerto Rico.”

But what excites Guerrero the most is not what others can gain from the exhibition. “This is coming from the position of artists that live the Puerto Rican experience daily, either in the archipelago or the diaspora, but they can’t evade being Puerto Rican” she says. “Perhaps it’s not the most political change, but it will make people rethink Puerto Rico.”