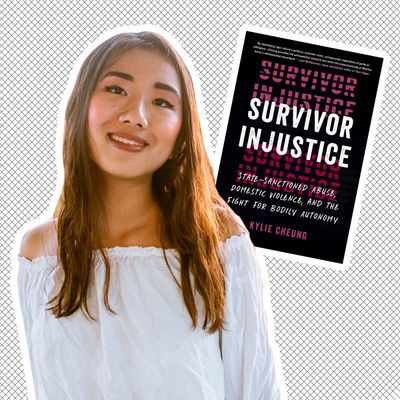

The first chapter of reporter Kylie Cheung’s Survivor Injustice: State-Sanctioned Abuse, Domestic Violence, and the Fight for Bodily Autonomy makes the argument that domestic violence is a form of voter suppression. Through a wealth of research and interviews, Cheung documents how political disenfranchisement is one of the less visible, but no less treacherous, ways that abusers exert control over their partners. When a survivor’s partner blocks them from casting a ballot or tells them who to vote for, they lose the opportunity to challenge the legislators who would limit their housing and health-care options or their reproductive autonomy, cutting off the resources that could free them from the abusive relationship.

This is just one of the ways in which Cheung, a writer for Jezebel, outlines how survivors are excluded from fully participating in public life. Taken together, they show that the American police state, carceral system, electoral politics, and capitalism are complicit in this oppression. “Domestic violence, in fact, is not just political, but quite literally a feature and consequence of greater systems of state violence,” she writes. “State and interpersonal violence are inseparable from each other, feeding each other in an endless cycle.”

Survivor Injustice asks readers to confront the structures that allow gender-based violence to flourish and to imagine community-based solutions that prioritize survivors’ needs rather than their abusers’ punishment. Cheung spoke with the Cut about the implications of the overturn of Roe v. Wade for survivors, how her experience with sexual assault informs her reporting, and what accountability for abusers could look like outside the carceral system.

What inspired this book for you?

I was really compelled by some of the new data showing increasing cases of domestic violence during the pandemic — which we tend to see with natural disasters or other major difficult national moments — and it was really concerning how that was coinciding with the 2020 election. Something I’d been thinking about for a while was how domestic violence is a prevalent but really underreported form of voter suppression. I started with speaking to different domestic-violence experts as well as survivors, who shared with me some of their experiences of having an abusive partner control their access and their ability to vote. Doing those interviews then compounded with the really important work around racial justice and the conversations around abolition that were happening in 2020 as well as the varying, very serious threats to reproductive rights that we were already seeing. I wanted to work on a project that would challenge our very narrow conceptions of violence and present a fuller image of how state violence and interpersonal, gender-based violence feed off of each other.

You bring this thesis home with so many examples, from abusers restricting their victims’ ability to vote to abortion bans. How was the process of doing all this research and making these connections?

There is an ingrained idea of domestic violence as a “private issue,” and we see the way that people are treated when they do come forward about these matters. If a powerful man is accused of abuse and people love his art or his work, it might be said that, “Oh, we should still let him do his art and let that aspect of his private or personal life be separate.” But it’s a workplace issue.

When we look at voter suppression and politics and the role of domestic violence, it’s not a private issue at all — it is a huge public-safety issue, and it has tremendous political implications. It impacts people’s access to public life, to health care. We’ve reached a point where you can see a horrific video recording of police brutality and there is an understanding that that is state violence. What I drew from those first interviews with survivors who had abusive partners who’d interfered with their voting and with survivors who experienced reproductive coercion is that it’s also a form of state violence when someone isn’t able to afford health care or housing, and so they’re forced to stay in an abusive and dangerous relationship.

A big part of the book is also navigating the carceral system. We know about the sexual-assault-to-prison pipeline. From the moment someone experiences gender-based violence or sexual assault, that trauma and the lack of support that survivors receive continue to unfold throughout the rest of their lives. Sexual assault is also the most financially costly crime for victims, and it costs the U.S. about $127 billion per year. That can make it more likely that someone would commit survival crimes, and that could increase their chances of being incarcerated. There was a lot that I was trying to wrap my arms around in this book, but my hope is that I was able to show how none of these are separate issues. Interpersonal violence and state violence are intertwined.

Your lived experiences — as an Asian American woman, a sexual-assault survivor, a journalist, an abolitionist — emotionally anchor the book but also offer a point of view that is regularly left out of the mainstream conversation. Can you walk me through the choice of weaving your own experiences into a deeply reported book?

It felt very natural, but at the same time, I also felt a lot of trepidation. Maybe that’s because, in recent years, there’s been a lot of pressure placed on survivors to share experiences that they might not be comfortable sharing in order to be believed. It should be the case that people are empowered to share as much or as little as they’d like. I tried to emphasize that there’s this problem of universalizing what a survivor’s experience looks like. If you look at, like, different people who have shared experiences with sexual assault, you’ll see, like, a variety of different politics and activism, and yet there’s such a monolithic understanding of what a survivor is supposed to look like after the fact.

I reference Chanel Miller’s story and her memoir, Know My Name, and how I see my own experience in it. Discussion around gender-based violence within Asian communities, at least in my experience, has been very repressed, and in western culture more broadly, there are significant issues with the hypersexualization of Asian women. It was important to me to be a part of showing the full range of experiences and identities that survivors of gender-based violence hold.

You argue in the book that, along with this monolithic understanding, there’s a one-size-fits-all policy response that relies heavily on a policing and carceral approach. You include a lot of research supporting that it is survivors themselves who almost always end up being criminalized rather than their abusers. Could you talk a little about reimagining this system?

Right now, we have this criminal legal system that’s innately punitive. You have about 40 percent of police officers who self-identify as domestic abusers, and in a quarter of cases, when women call the police for intimate-partner violence, they’re arrested or threatened with arrest themselves. I try to present a range of different approaches that can respond to sexual harm without reproducing additional harm. Some ideas that are presented by Alexandra Brodsky in her book Sexual Justice were a really big inspiration. It might not seem as big or bold or imaginative as abolition on the surface, but even seeing different forms of harm that would go into the criminal-court system as civil matters could be a big step toward addressing this in more timely and less traumatic ways for survivors.

It was really heartening to see a lot of conversations about restorative and transformative justice in 2020. At the same time, something that’s been concerning is this co-opting of some of the language around restorative-justice practices that is used to defend abusers and take responsibility away from them. What can be misunderstood is that restorative-justice practices require people to take responsibility for the harm that they’ve caused and own that and be an active part of repairing that. It’s a lot less arbitrary in some ways than the criminal legal system. It’s not meant to be punitive for the sake of being punitive, but it does require accountability. What makes it very difficult to have restorative-justice approaches coexist with a criminal system is that what survivors might need in order to heal and feel supported is going to differ across the board.

You connect the fight for abortion access and reproductive justice with state violence and domestic abuse itself. Can you talk about the overturning of Roe and what it tells us about gender-based violence?

Abortion bans are a form of gender-based violence. If you raise this issue of a partner tampering with someone’s birth control, or taking actions that force someone to get pregnant when they don’t want to, I think, to a reasonable person, that would present as abusive behavior. It’s interesting that when our government legislates similar behaviors, it’s seen as, “Oh, that’s just politics.” Something I reported last month is that the National Domestic Violence Hotline revealed that they received essentially double the amount of calls related to reproductive coercion in the year after Roe was overturned. I spoke to someone at the hotline who talked about this caller whose partner was intercepting her birth-control pills and she got pregnant and had an unwanted pregnancy in a state that had banned abortion. The helpline has also heard from people whose partners were telling them lies or manipulating the confusion around abortion bans. So there were partners who told their victims, “If you have an abortion, I’ll call the police because it’s illegal, and you’ll go to jail.” It’s such an obvious outcome to all of this, you know? And we know that homicide, often by intimate partners, is the leading cause of death for pregnant people.

We also know pregnancy criminalization is a prevalent issue. In 2019, there was a case of a woman in Alabama who was shot in the stomach while pregnant and miscarried. Charges were brought against her because of that. This creates so much room to further the criminalization of survivors. One recent case is the Nebraska teenager who was charged in connection with self-managing her abortion. She said a factor was that she was in an abusive relationship. And now she’s going to jail for 90 days. It speaks to the intersecting ways that the carceral system is harmful to survivors and pregnant people; those are inseparable realities.