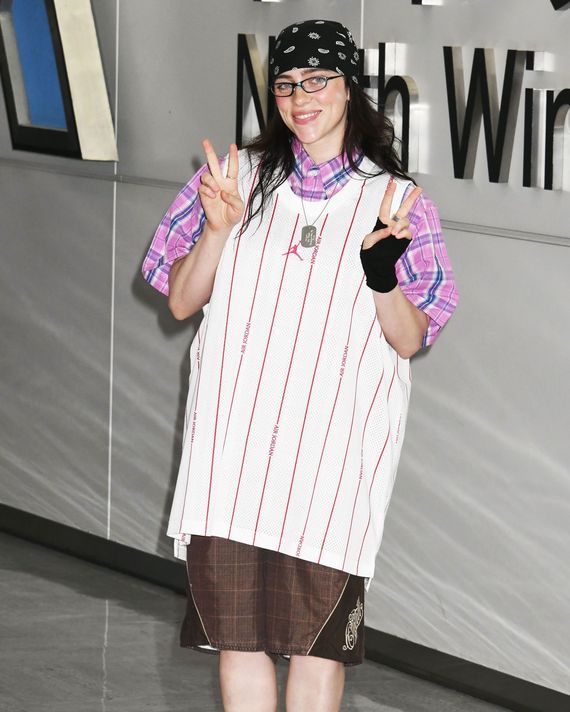

A week and a half ago, Chicken Shop Date hosted Billie Eilish, confirmed girl kisser and loud-and-proud munch. It was big news, a public test of queer sexual charisma — especially because Chicken Shop’s host, the professional flirt Amelia Dimoldenberg, is more experienced at sparking romance with male celebrities. Eilish dressed up for the occasion, looking like a born finesser in a baggy shirt and pants, green cap turned sideways over a bandanna, and computer-geek glasses framing her baby blues. It’s the type of outfit that makes it easy to imagine Eilish rubbing her hands together as she checks out a woman she thinks is fine. The chemistry was palpable. Call her Ms. Steal Yo Girl.

The Twitterati had a field day, issuing hundreds of quips to the effect of “why is she dressed like that?” Since Eilish officially came out as queer last year, she’s been more overt in her sexual expression. She told Rolling Stone in the lead-up to her new album, “I realized I wanted my face in a vagina” and parlayed that thirst on Hit Me Hard and Soft’s lead single, “Lunch,” on which she teases that she could “eat that girl for …” well, you’ve got it. Corresponding with her gayer public identity has been a dramatic change in presentation. Early this year, in the midst of Barbie Oscar campaigning, Eilish dressed prim and secretarial, a prep-school damsel in bows, blazers, and Chanel tweed. Now, depending on who you ask, she’s gone full “hey mamas” lesbian or David Foster Wallace; to quote one viral tweet, “why she always dressed like Chingy.”

Eilish’s style has attracted scrutiny since the beginning of her career, when she was a scowling, nonconformist teen with lime-green roots and a taste for streetwear. Both musically and stylistically, young Billie seemed to be taking cues from male rappers more than her female peers; she scrambled the pop mold with whispery, macabre songs indebted to trap and stepped out in hypebeast-y outfits that hid her figure. Eilish wore baggy clothing as part of a deeply understandable effort to avoid sexualization, lest conversations about her body eclipse the narrative. “Nobody can have an opinion because they haven’t seen what’s underneath, you know?,” she said in a Calvin Klein ad. Her fits — logo-fied, tentish, disobedient — weren’t simply functional. Some saw a subversive refusal to deliver femininity; others saw evidence of anti-establishment posturing, another privileged white kid not giving credit where it was due.

By then, though, the pop star had already pulled an about-face. In 2021, she shocked the masses by gracing the cover of British Vogue in blonde curls, a rose-colored bustier, and latex gloves, transforming from punkish young iconoclast to golden-age bombshell. The backlash was instantaneous. Eilish recounted to Elle, “I lost 100,000 followers, just because of the boobs.” The Vogue cover teased the old-Hollywood theme of her second album, Happier Than Ever, which she envisioned as a “timeless record,” inspired by (white) jazz singers like Julie London and Frank Sinatra. Later that year, for her Met Gala debut, Eilish paid homage to Marilyn Monroe in a peach-colored Oscar de la Renta ball gown. Eilish said her sartorial 180 was a reaction to feeling pigeonholed: “I felt pretty trapped in the persona that people had of me,” she told NME. “I wanted to have range and to feel desirable, and to feel feminine and masculine — and I wanted to prove that to myself, too.” But to skeptics, it was irritating proof of how carpetbagging white artists are free to try on then cast-off Black aesthetics at will. (Eilish is, to put it mildly, an inelegant interviewee, and her earlier, haphazard remarks about rap hyperbole didn’t help.)

In a sense, Eilish’s current style is a return to form. “My immediate reaction [to the Chicken Shop Date outfit] is that Billie Eilish is just being Billie Eilish,” says Emil Wilbekin, an assistant professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology, editor-at-large at Essence, and former editor-in-chief of Vibe and Giant. The pop star is back in tomboy mode, with a “hard-edge, hyper-masculine type of look” indebted to West Coast gangsta rappers, as he describes it. (The rapper Armani White crystallized the associations between Eilish and street life on his 2022 viral hit “Billie Eilish”: “Bitch, I’m stylish/Glock tucked, big T-shirt, Billie Eilish.”) The primary difference is that Eilish’s look now seems more curated. “Her references are so on point that it’s kind of scary,” Wilbekin asserts, pointing to the oversize layers — a functional choice for hustlers hiding weapons and contraband — military pendant, chunky watch, and bandanna under the tilted cap. (And then there are the fake glasses, which my rap-critic friend said were “giving E-40.”) “White girl does ’90s hip-hop” is a concept that’s bound to reignite cultural-appropriation accusations; sure enough, one widely circulated criticism of Eilish’s Chicken Shop outfit reads, “white gays equate masculinity to black culture without fail each time.” Wilbekin doesn’t share the concern: “When I look at kids in New York City, they’re all dressed like that.” But it’s the fastidiousness he mentions that gives critics pause; people would have less of a problem if she were just wearing a big shirt and pants.

Hannah McElhinney, co-creator of the LGBTQ+ education resource Rainbow History Class, brings up a more contemporary reference. “What I got was ‘hey mamas’ lesbian,” she says, referring to a TikTok trope of an unapologetically flirtatious masc lesbian, usually in a backward cap and sports bra or white shirt. The term is mostly lighthearted but can have derogatory connotations; the “hey mamas” is a kind of lesbian fuckboy, cringey, narcissistic, and oblivious. (The name derives from how said lesbians supposedly introduce themselves to their romantic targets.) In some way, though, the “hey mamas” trope represents progress, a broadening of the very limited pop-cultural templates for queer women; at the very least, it’s a sapphic in-joke as opposed to an external imposition.

The “hey mamas” lesbian runs counter to the antiquated image of lesbians as hairy, sexually frustrated man-haters in lumberjack fits, or to use a more contemporary example, the meek femme shyly probing her crushes “do you listen to Girl in Red?” There’s an ego and willingness to put your sexuality out there, compared to some of the more mainstream lesbians whom we’ve seen in popular culture,” McElhinney says. Rudy Jean Rigg, Rainbow History Class’s other co-creator, adds: “Masc queer women are not being coy about the fact that they want to eat people for lunch.” For all of the controversy surrounding her presentation, Eilish was an extraordinarily sexy Chicken Shop Date guest, more worthy of heartthrob status than the majority of celebrity men who’ve appeared on the show.

Eilish is unique because she “doesn’t want to play into traditional cisgender norm fashion politics,” says Elena Romero, Wilbekin’s colleague and the co-curator of an F.I.T. exhibition celebrating 50 years of hip-hop style. At a certain level, it’s refreshing to see a celebrity of her stature assert herself as a sapphic sex symbol in more down-to-earth masculine apparel. (Taylor Swift could never.) She’s not the chic, cosmopolitan girlboss conjured by Lesbian Chic, a marketing trend kickstarted by a 1993 New York Magazine cover of k.d. lang. As Corinne Bickel reflected recently in High Snobiety, the Lesbian Chic “stood in sharp contrast to the baggy, androgynous clothing adopted by the [1970s] Anti-Fashion movement.” She wore power suits, blew out her hair, carried around a designer handbag; she dressed “masculinely enough to appear queer but femininely enough to still fit into a heteronormative world.” Now the dial has turned back to androgyny, and it’s not just queer women in laid-back, utilitarian outfits. When Wilbekin says that Eilish dresses in line with her generation, he’s talking about a cultural trend toward basics and workwear; wherever I go, I see young people of all genders in Hanes tanks, big jorts, and chains. “Particularly for this younger generation, overly glamorous fashion doesn’t speak to them because they can’t afford it,” says Wilbekin. “It’s easier to do something that’s classic, that’s cool, that is easy to make your own by just adding jewelry or different sneakers.” Subgroups overlap in style: ’90s rappers wore Carhartt and Dickies and so do contemporary queers. Loose silhouettes accommodate and obscure, helping mitigate dysphoria and discomfort.

Perhaps there’s another dynamic at play in the controversy surrounding Eilish. However exciting the so-called “sapphic renaissance” in pop music may be — think Chappell Roan, Reneé Rapp, MUNA, and boygenius — the narrative has mostly centered a small subgroup of white cis femmes to the exclusion of of everyone else. “We’re not seeing butch lesbians, disabled lesbians, fat lesbians. We’re not seeing like trans-masc people in the spotlight,” McElhinney observes. Mainstream music fans and media tend to overlook artists of color like Young M.A, 070 Shake, Kehlani, and Janelle Monáe. Eilish may be slightly more masculine presenting than the movement’s other public faces — in the words of one meme, “the butchest girl Twitter can handle before they start getting scared” — but her image is still more palatable than that of the studs she inadvertently emulates. One thing is for certain: It’s difficult for anyone to learn how to express their queerness in a way that feels organic. “Some artists are stars that take a U-turn and become queer,” says McElhinney. “It’s harder for them, because they have to do all their awkward baby gay shit in the public eye.”