Because no two paths to parenthood look the same, “How I Got This Baby” is a series that invites parents to share their stories.

In December 2021, Katerina, a single mom to a 20-month-old daughter, was working in marketing in Kyiv when she decided the time had come to pack up her apartment and move back to her hometown of Chernihiv in northern Ukraine, where her mother still lived. She was recently separated from her husband and pregnant with twin boys. She knew she would need extra help once her babies were born. Also, life in Kyiv had begun to feel somewhat unnerving; Ukrainian tanks had arrived as rumors of a possible Russian invasion swirled.

Once she moved into her mother’s apartment, Katerina rented a house nearby and started to prepare for her sons’ arrival. Despite the increased military presence in the city she’d left, she felt confident that war was not a real possibility — a sentiment that many people in her country shared, she says. “We got furniture and very nice beds for the kids,” she recalls. “Very nice. We assembled everything because no one believed that the war would start, actually.” Over the next few months, Katerina’s pregnancy proved complicated — she was hospitalized twice, both times for two-week stays — but the babies continued to grow well.

In early February 2022, Katerina and her mom stocked up on groceries at the urging of some friends. “People were panic-shopping,” she says. “I don’t remember who insisted, but about a week or so before the war started, we bought a couple months’ worth of food — mostly canned food and beans.”

The last furniture for the twins’ nursery arrived on February 23. Russia’s bombing of Ukraine began the next day. Katerina was 32-weeks pregnant. She recalls the harrowing and chaotic days, months, and years that followed.

On the first ten days of bombing

I was asleep with my daughter, and my mom woke me up at 5 a.m. and said, “You need to get up! The war started!” She had heard explosions. I couldn’t walk very well because my pregnant belly was so heavy, so we couldn’t go down into the basement shelter of the apartment building. Instead, we decided to hide in the house we were renovating — it was me, my daughter, and my mom. First we tried to stay in a deep cellar, but it was so cold, minus-10 or -15 degrees. We were really scared of getting sick. There was also this smell of mold. We thought: It makes no sense to catch some infection. So we hid in the next deepest thing in the house — a space under some stairs, about one meter by one meter. We were only about half a level below ground.

On that first day, there was really intense bombing. On Instagram we saw that the Russians were coming into the city. At one point, there was a huge explosion, but because the windows in the house were not that old, the glass didn’t break — the windows just opened. In other nearby houses, the glass was shattered.

By the third day, all the houses around us were completely bombed. I remember sitting with my daughter, crying and hugging her tightly and asking my mom what we should do. My daughter stayed strapped in her stroller most of the time — eating there, watching cartoons when there was still electricity. On the third day, I went upstairs to see what was happening and saw that the building next to ours was burning and the building opposite to us was completely destroyed.

I took photos and videos to send to my father, who I don’t have much of a relationship with. But he lives in St. Petersburg. He responded: “Everything is a lie.” He told me the videos I took weren’t real, that they were “brainwashing us,” and that the fighting would finish “in a few days.”

We went back into hiding. The same day, Russians bombed the city so much — the kindergarten I attended was completely bombed to nothing; it was like one brick. Then the Russians bombed the epicenter of Chernihiv. We were following these Telegram channels because we still had internet connection; we still had electricity to charge the phones.

The military knew we were there, and that I was pregnant — I can’t remember how they knew. Maybe friends told them, or the hospital. After ten days, I got a call saying, “We need to evacuate you immediately. They’re bombing so hard, everything is bombed around you. The tanks are coming. You have to go.”

On getting evacuated to a hospital

Military escorts arrived to drive us to the hospital about a kilometer away from where we were hiding. It was so crazy — the military with these guns. They just put us in a car and said, “Fast, fast, fast, the tank is coming! You need to be so far!” It was terrifying. They drove us so fast to the hospital and put us in the shelter below it. But it wasn’t really a shelter — just a floor one level below ground. There weren’t enough beds. My mom and daughter stayed together, but I was sent to a special room farther underground. It was very cold, very damp — it was an atomic-bomb shelter they built just after World War II and it hadn’t been maintained since then.

The other people there were pregnant women who either had complications or were close to giving birth, or had just given birth. There weren’t enough beds. Instead, they put us on these things to carry dead bodies, dead soldiers — gurneys or stretchers — or on doors they pulled from somewhere. I was already in so much pain. I couldn’t sleep. And it was so cold. I think at that point there was no gas but there was still water. And there was no turning off the light at all; it only turned off when the power went out.

When I got down there, I learned that there were no ultrasound technicians because they had all fled. There were a lot of women who lost their babies at around six months, seven months because there was no one who could see inside their stomachs. The doctors who had stayed were mostly women.

On having an emergency C-section

After three or four days down there, separated from my mom and daughter, I started having contractions, and my body swelled. I could tell that something was wrong. I couldn’t walk. The doctors told me they needed to perform an emergency cesarean because my body was shutting down and they couldn’t see what was happening with the babies. They brought me up to the first floor, where a woman gave me anesthesia and inserted the catheter and then left me alone in a corridor next to a window. It was terrifying. I was shaking from the anesthesia and scared of the glass shattering and injuring or killing me.

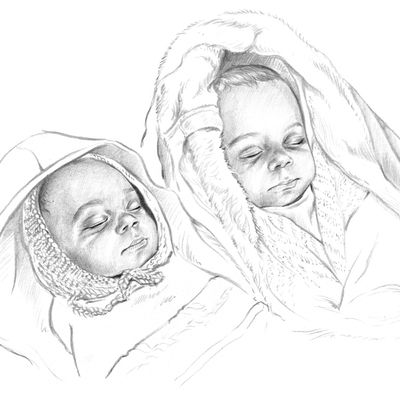

To perform the C-section they moved me into a regular room. I could see everything during the operation. The bombing was so intense that the windows were shaking, and I could hear gunfire. During the surgery, I remember the doctors saying they’d never seen so much fluid in a woman’s abdomen. When the babies were born, they showed them to me briefly before taking them away to intensive care. They said, “We don’t like how they breathe.” They were so thin.

The two surgeons who performed the cesarean were both women whose houses — which were, coincidentally, right next to my house — had been destroyed by bombs. They had been staying in the hospital since then because they didn’t have homes.

On trying to recover from surgery in the bomb shelter

After my C-section, I was left alone for two hours. No one came to check on me. The pain was unbearable. I was finally moved back down to the shelter and they let me stay on a normal bed for just one day. Then they asked me to lay on a door. They were giving me pain medication, but it was not really working. And instead of being kind and gentle, the nurses were screaming at me. They tried to make everyone who had a C-section leave the shelter after one day — and those who gave birth vaginally, they were kicking them out after a few hours. But I said, “I’ll not go anywhere. I cannot walk!”

I didn’t see my babies for two-and-a-half days. I was pumping breast milk by hand and sending it up to them. When they finally brought me the twins, they told me one wasn’t doing well and took them back to intensive care. I was so scared.

A day or two later, Russia bombed the dialysis center near the hospital. Even in the shelter, where you could barely hear anything, the explosion was so loud it woke me up. I thought they had bombed the hospital itself. I started crying. I thought, My babies are there, my daughter is there, my mom is there!

In the shelter, we weren’t allowed to use our phones — the doctor in charge believed that the Russians would bomb places where they could detect phones. The medical staff was constantly screaming at us to turn them off. I tried to explain that my babies were in intensive care and my daughter was with my mom in a different part of the hospital. I started crying because I didn’t know what was happening with them.

There was one kind nurse who came over to calm me down, but the doctor on duty yelled at her, saying, “Don’t help her, leave her alone.” The doctor then turned to me and started shouting that I needed to stop crying. It was so dehumanizing — a horrible experience for me.

I was terrified at that point, but mostly my emotions were blocked. When you are in a situation like this, you don’t have the space for emotions. If something happens, you need to run.

On what she saw in the hospital

During that time, there were two sets of triplets born in the shelter — one was the first set of natural triplets in the region in five years. One of the mothers completely shut down. She refused to breastfeed, took a pill to stop lactation, and wouldn’t even look at her babies. She was depressed.

There was no electricity in the hospital or in the NICU. They tried to use a generator, but it hadn’t been checked in 70 years. When they turned it on, it filled the entire floor with toxic smoke. The babies needed heat to survive, but there was nothing.

I knew that I had to get myself and the babies out of there. The hospital didn’t want me to take the babies because one of them was still in intensive care, but I insisted. I signed the paper and discharged them at seven days old.

On trying to fleeing Chernihiv

After the hospital, we went to my mom’s apartment to spend one night. The military almost didn’t let us in, saying that it was a gray zone. That day was the scariest day, maybe.

Russia was dropping the big, big bombs around us — they were only one or two kilometers away. Maybe closer. We slept in the corridor of the building. My friends and ex-husband were all trying to find someone to come get us. Because this building was so close to the Russians, not everyone had courage to enter this area. But one person, finally, came. He was half-military — he brought us to a bus in the center of the city. He was a complete stranger, very brave, who went inside this gray zone and didn’t get scared.

We left with one bag. We didn’t even take strollers. The babies were wrapped in big blankets. I can’t remember exactly how we managed to carry all three children to the bus, but once we were on it, we asked some girl to hold one of the babies. The bus ride to Kyiv should have taken an hour and a half, but it took seven hours because we had to use roads made by tanks. I don’t remember how I was feeding the babies. But because they were preterm, they were always sleeping, so that was a relief. All the children on the bus were vomiting from the shaking.

We left the city on the 14th or 15th of March. And on the 16th, my house was completely bombed. Everything was destroyed — all the furniture we’d bought, everything. One day later, the Russians bombed the bridge we needed to cross to get out of the city. If we had stayed, we would’ve been trapped.

On searching for a new home

We spent one night in Kyiv in my twin sister’s apartment. The bombings were so intense, but it was so cold, we couldn’t go underground with the babies. The next day, we tried to cross to Moldova in a private car organized by my ex-husband, but we were turned away at the border because we didn’t have birth certificates for the twins. We had to go back to a nearby city to get them, which took another day. We also took the babies to a hospital to get a checkup, provided for free by the government. They had lost 500 grams — one-fifth of their weight. But otherwise they were okay.

Once we got to Moldova, my ex-husband met us with a van. We drove for four days to Denmark, where he brought us to a shelter with a lot of people who were sick. After a week or so, the twins developed an infection. They tried to move us to another shelter that was a seven-hour drive away. I said that we cannot afford to do that with these small babies! So I wrote in groups on Facebook, “Can you help us please? Someone?” I knew that people were taking Ukrainians in — and one family took us.

My mom decided not to stay with us at that point; she went back to her apartment in Chernihiv to take care of her father.

On living with a family in Denmark

The house was very nice and safe, in a private suburb. The wife, who taught children with special needs, was Danish, and the husband, a police officer, was from Germany. They provided us with food, some clothes, and everything the kids needed. I know the government partially covered it. They also provided us with a home full of love and respect, and an amazing atmosphere. They spoke fluent English. They gave us their daughter’s room — it had a loft bed. She was only one day younger than my daughter.

I mostly spent my time there pumping, breastfeeding, walking, eating. I was trying to start feeling something. I even tried to start working on an idea for a beauty app I had.

But within just a few days, one of the twins started turning blue and we called an ambulance. They took both the babies — they had pneumonia, and we spent seven days in this ICU. The babies had all of these tubes … I honestly don’t remember a lot. Thankfully, they survived, and we were able to go back to the family’s house.

We were with the family for about five months. At that point, we still hadn’t gotten any paperwork from the Danish authorities; no progress toward getting permanent residence. I calculated the cost of living there permanently and realized I couldn’t afford it. The family was so generous, but I had only a small room — eight square meters — for me and three kids. No real help, no real support from the Danish government. So I got scared and I worried: If the twins are sick again, who will stay with my daughter? I was also afraid the wait would be too long for my daughter to go to school. I got scared she wouldn’t get a place.

On traveling in search of a permanent residence

I was so hesitant, but I asked my ex-husband for help. He brought us to Turkey, where he lives. Thankfully, my friend who had been living in Istanbul for a few months because of the war came to Bodrum to help me. First, we went back to Moldova because I needed to get my passport from Ukraine — I’d been traveling all this time with another ID. It took an incredibly long time to get my new passport delivered. Ukrainians had to send it more than 700 kilometers from the main office to the border with Moldova. We waited in Moldova for a month and a half for the passport to arrive because it had to go through the diplomatic mail system, which was extremely slow. Once I learned it arrived, I had to travel to a small city in the Odessa region, 20 minutes from the Moldavian border, to pick it up. I left my children with my friend for that trip. When I returned to Moldova with the passport, the twins were seriously ill with pneumonia for the second time and we ended up back in the hospital in Moldova for another ten days. The hospital had a rule — one baby bed per parent — so I slept with one twin in the bed with me. My friend watched my daughter in the apartment where we were staying.

I tried to figure out where we should go. I thought: The kids are always sick. It’s impossible to live in these countries with such cold climates. So we looked for somewhere cheap and decided to fly to Tunisia. We connected through Rome, but as soon as we landed in Tunisia, the border agents accused us of coming to the country for prostitution. With baby twins and a 2-and-a half-year-old! They said that for a Ukrainian to enter Tunisia without a visa, you need to fly from Ukraine. I said, “It’s funny. It’s really a joke.”

They held us at the airport for 24 hours, then gave us a military escort — a huge convoy — to a plane and sent us back to Rome. They tried to make us pay for tickets. We said, “We’re not paying for anything. It’s your fault!”

We stayed in Rome for two weeks — friends gave me money for Airbnbs. But we understood that we could not stay there long — it was too expensive. We decided to try to move to Egypt, because it seemed affordable and had a good climate. We stayed there for a month, then we moved to Jordan, where I live now.

On her life today

I’m now living in Jordan with a new partner and my children. The boys will be 3 in March. Now they’re healthy. They are almost the same height as my daughter! They no longer have any signs of being preterm.

I have a family residence. The twins are in nursery school and my daughter is in kindergarten. The kids speak English and a little bit of Arabic and Russian. I’m working on the app I started to develop in Denmark.

My mom is still in Ukraine, with my grandfather, but I cannot go back. Even though we have an apartment there, it’s too hard. I had nightmares for a year. My daughter used to scream every night for at least half an hour. After a year, the screaming went down to about once a month.

A couple of years ago, I saw that the president of Ukraine gave this doctor who berated me at the shelter some kind of recognition. I couldn’t believe it. No one has asked us about our experience or what we endured.

I don’t know when I will be ready to return to Ukraine. I love Ukraine. But it is hard to think of any future in such a terrible situation. They’re still bombing. Just last month the Russians bombed an elite building, one that people never thought could be targeted. It was in an area with expensive, modern complexes — places where people had believed they were somewhat safe. There’s another big luxury compound nearby that hasn’t been hit yet, but after this bombing, no one feels safe anymore.

I can’t imagine bringing my children back to a situation like that, to start their lives underground. Honestly, I don’t understand mothers who choose to stay. They say it’s too complicated to leave or that they have no options, but there are always choices. You don’t need to stay in a war — to traumatize yourself and to traumatize your kid. I judge them, even though I know that it’s not really good to judge someone. But it comes from inside me. As a mom who wants to save her kids, I don’t understand why they stay with their kids there.

I’ve been in touch with my father in Russia a few times since I sent him those photos and videos. After a year, I asked him, “So, did it finish?”

Want to submit your own story about having a child? Email [email protected] and tell us a little about how you became a parent (and read our submission terms here).

More From This Series

- The Mom Who Gave Birth While Incarcerated

- The Mom Who Is Trying to Become a TikTok Influencer

- The Mom Who Went Into Heart Failure at 20 Weeks