The other day, my mother called me “Hitler.” Someone who wanted all Jews to lie down and die, who thought all Jews were parasites. The war, she said, was because of people like me — self-hating Jews like me. I had commented that killing 4,000 children in a month was a tragedy, and that was the response — immediate, reflexive. That I, who have kept even the smallest and most obscure fast days and holidays, who have kept kosher all my life, crave Jewish death.

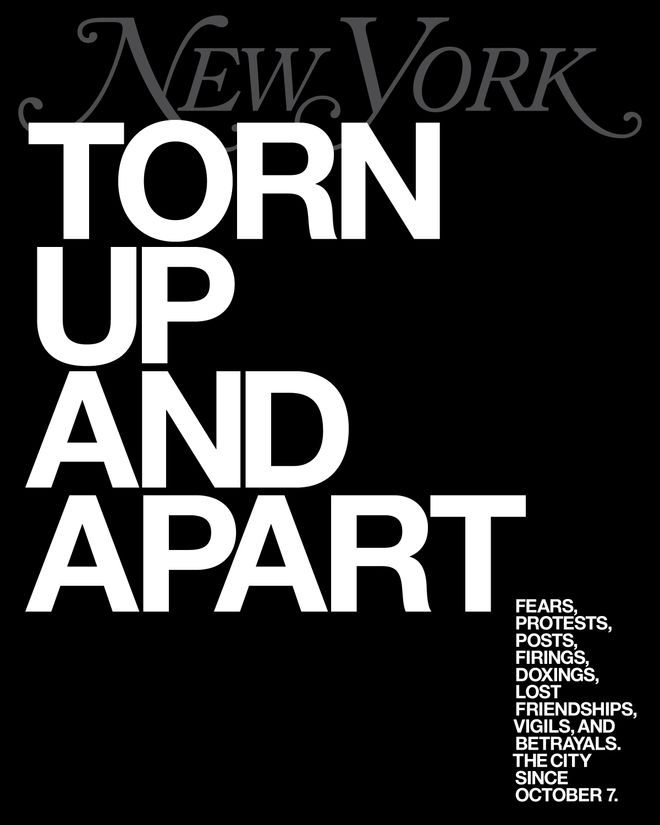

I am an Orthodox Jew in an Orthodox family in a heavily Orthodox neighborhood of New York City, and there are constant events — vigils, Shabbat dinners with empty seats at tables for the hostages, rallies in support of Israel — which my family members attend. There are upcoming missions to Israel, neighbors and friends flying there to give what help they can to relatives who are displaced or have spouses on the front lines. There is genuine suffering and a protective shell of anger around it — anger that so many people deign to have opinions on the slaughter in Gaza and a conviction that any opposition to it comes solely from antisemitism. There is antisemitism everywhere, which makes it worse. The paranoia is palpable in my community: It seems to come from some ancestral well of fear, the very fear that brought us to these shores in the first place. More of a confirmation of priors, of the hostility of the world, than some new revelation.

Cover Story

Family members are experiencing what I can only term an attenuated form of nervous collapse. Crying in the middle of the day, not sleeping. Dwelling on dark fantasies that combine the past and the present. I had grandparents who survived the Holocaust, just barely, and I have multiple relatives in Israel, some deployed, some left to tend to their homes and families alone. Everyone is a haunted mess, and jingoism appears to be the defense mechanism of choice. The war is the subject of every conversation. Any other topic feels extraneous, even small happy things. I attend Shabbat meals in a cloud of grim silence. It is painful to watch people around me whom I have known for their inquiring minds and strong sense of morality become uncritical flag-wavers, watch them dismiss massacres as disinformation, watch them advocate more and more violence. They treat cease-fire as a dirty word. It is like suddenly being surrounded by génocidaires, seeing familiar and beloved faces melt into Greek-theater masks of rage.

The family chat on WhatsApp is always buzzing. Everyone is in multiple WhatsApp groups: groups for Jewish women, groups in support of Israel, groups for volunteers. I get endless forwards to condemn such-and-such official, to laud Eric Adams, to call for the ouster of still another official, to condemn universities and student groups. There are tweets, IDF fundraisers, critique or praise of public statements, ceaseless petitions. The phones are always going off. More photos. Photos of mutilated children, videos of slaughter. Who could withstand such an onslaught and not be changed?

TO DO:

• Buy socks and ceramic vests for the soldiers.

• Line up around the block for this Israeli café whose staff members showed up wearing Palestinian-flag pins, so the owner confronted them and they quit.

• Call your congressman to stop a cease-fire.

• Send small trinkets to your loved ones and hope you’ll see them again.

• Check out this Instagram photo of an eye, weeping, with a Jewish star Photoshopped over the iris. This Facebook meme and that one …

I deleted Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook from my phone.

The Shema — the central prayer of our faith, the quiet nighttime prayer, the final prayer of gentle release from life — is now recited by those launching themselves into battle, a war chant. What a sacrilege. What a precipice! After lighting Shabbat candles, we say a prayer for the IDF.

Since I was told to stop protesting or face excommunication, survival in my community and family has become a matter of silence. To go on, don’t say a word. Dismiss the images of Gaza pockmarked and scarred by fire, accounts of children dying of thirst, of ambulance convoys struck by missiles. Assume everyone is a human shield; assume they were never human in the first place. And so on, every day. In synagogue, the rabbi cites II Samuel in his sermon: “David inquired of the Lord, ‘Shall I go up against the Philistines? Will You deliver them into my hands?’ And the Lord answered David, ‘Go up, and I will deliver the Philistines into your hands.’ ” The connection between Philistine and Palestine is dubious but drawn nonetheless; earlier in the Book of Samuel, David collects 200 Philistine foreskins as a dowry to marry the king’s daughter. I can’t stop thinking about it. That grisly pile.

I stopped going to synagogue.

It would be easier if the war weren’t the only subject of every conversation. If there weren’t always another call to action. But there always is. And there is always more dying. American Jewry is distinct from Israel, but among the Orthodox community, particularly the Modern Orthodox community in which making Aliyah, moving to Israel, is pushed on us as a higher form of life from our earliest days, the interconnection is inescapable — everyone has a relative in peril. There’s a sense of oneness and of danger, but there is a shiver of hysteria in it here in New York: perhaps a sense of guilt that we are safe while our loved ones are not; perhaps a fear that the dream of Israel, the dream that we wouldn’t have to run anymore, is breaking down; perhaps, and maybe this is just wishful thinking on my part, a creeping awareness that the onslaught of propaganda protests too much, obscuring the slaughters carried out indirectly in our names. I think a hollowed-out heart, a heart consumed with revenge, renders its own defense moot. But at present, I can only keep my grief silent while all around me engage in a full prostration of weeping.